There’s more than one way to see the constellations. Here’s a look through Native American eyes.

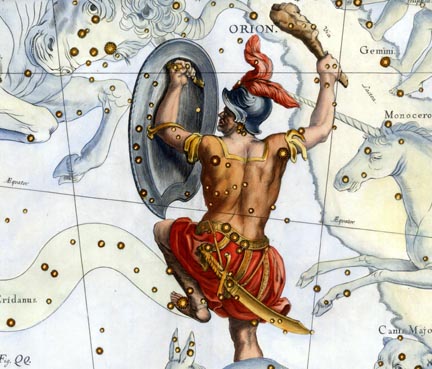

Johannes Hevelius, 1690

Orion the Hunter is arguably one of the most recognizable constellations in the sky. Striding the celestial equator, he charges up from this eastern horizon around 9 o'clock in late November, club in one hand and shield in the other.

Weaponized and ready, this dude's got hunting on his mind.

But there's another Orion. In the eyes of the Ojibwe people, one of the largest groups of Native Americans on the North American continent, Orion was and still is Biboonkeonini, the Wintermaker. Want to blame someone for frozen fingers and all that snow you'll soon be shoveling? Wintermaker's your guy.

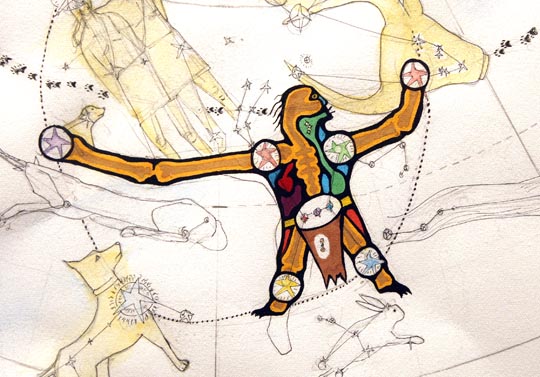

Annette Lee

The Wintermaker, a skilled canoeist, ushers in the cold and winds that characterize the season. Northern hemisphere skywatchers associate these same qualities with hunterly Orion, but the western character and myth have no direct seasonal connection like the Ojibwe constellation. Still, it's fascinating that both figures are formed of nearly identical stars, testimony to the striking pattern and strong impression Orion–Wintermaker made on two very different cultures.

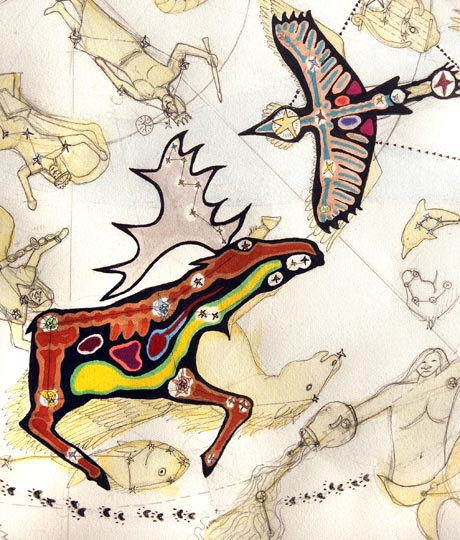

Annette Lee

Wintermaker is joined this month by Ojiig the Great Fisher (Big Dipper), a weasel or marten-like animal considered a great hero by the Ojibwe people. Legend has it he freed the birds and season of spring by tricking their captor.

On a dark night, we can trace the stars forming the bucket of the nearby Little Dipper (Ursa Minor). Maang the Loon resides here. He's a transcendent symbol, standing at the tenuous border between the material and spirit world in Ojibwe mythology. If you've ever heard a loon at night on a camping trip, you'd be inclined to agree. Is there any sound that better embodies the feel of wilderness? Here it is (click left end of bar to play):

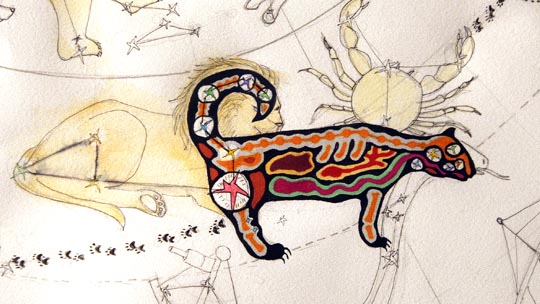

The basis for our modern list of 88 constellations goes back at least 6,000 years to the peoples who lived in Babylonia, now modern-day Iraq. They did one thing we still do best: connect random, unrelated objects into patterns. What better place to play this game than the star-sprinkled sky? Some of their patterns we still recognize — a lion (Leo), a scorpion (Scorpius), and a bull (Taurus), among others.

Annette Lee

The ancient Greeks and Romans added their own patterns to the mix, bequeathing us the 48 classical constellations. In the first half of the 15th century, Europeans created new patterns from hitherto unfamiliar southern hemisphere stars seen for the first time during the oceanic voyages of discovery. Still later, mapmakers and astronomers filled in little gaps between constellations with small additional figures. Some tried to sneak in the likes of a typewriter (Officina Typographica), a stargazing fish (Uranoscopus), and toad (Bufo), but sadly, these and others didn't make the final cut. The newest constellations, created in the mid-18th century when astronomers broke up the unwieldy Argo Navis, the Ship Argo, are Carina the Keel, Puppis the Poop Deck, and Vela the Sails.

Annette Lee

Constellations were standardized and their borders clearly defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in the late 1920s under the leadership of Belgian astronomer Eugene Delporte of the Royal Observatory of Brussels. Since then, no one's messed with boundaries or, for that matter, made up new constellations. Standards were needed so that astronomers around the planet could agree on what stars, particularly newly discovered variable stars and novae, belonged to what constellation.

St. Cloud State University

We know and love the traditional constellations. Many of us have formed lifelong associations with their seasonal arrivals and departures. But sometimes it's nice to switch lenses and see how others see the sky. It's not only fun to connect the dots to make new patterns; at the same time, we broaden our understanding of another culture. No matter Greek, Polynesian, Chinese, or Ojibwe, each civilization imbues the starry heavens with their own unique vision of life. Instructive stories, moral guidance, and lessons in human fallibility have been heaped upon the stars for you and I to ponder on the next clear night.

All the beautiful paintings used in this article were created by Annette Lee, assistant professor of astronomy and physics at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota and member of the Dakota-Sioux tribe. Lee also directs the planetarium at the university and researches Ojibwe and Lakota star lore and mythology. She's currently involved with the Native Skywatchers Project, an initiative to revive and celebrate indigenous peoples' connection to the stars. See her complete Ojibwe star map and Lakota map.

Curious about the origin of star names? Check out the Dictionary of Modern Star Names!

5

5

Comments

Alan

November 14, 2014 at 2:23 pm

Is there a way to get a high quality print of the Ojibwe and Lakota maps?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Annette-Lee

November 14, 2014 at 5:15 pm

Hi there! Thanks Bob for the article and getting our work out there….

Here is the link to purchase the maps! http://web.stcloudstate.edu/aslee/ Scroll down until you see the maps.

or email: [email protected] at the SCSU American Indian Center

Miigwech, Pidamaya.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Annette-Lee

November 14, 2014 at 5:18 pm

Also one clarification, The Ojibwe Giizhig Anung Masinaagan - Ojibwe Sky Star Map was painted by: myself and William Wilson and created by: myself, William Wilson and Carl Gawboy!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

November 14, 2014 at 7:55 pm

Thanks Bob and Annette, and all your colleagues. Now that I know the IAU constellations visible from mid-northern latitudes, I'm getting interested to learn the constellations and sky lore of other cultures. Could you recommend any books?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob

March 13, 2017 at 3:41 pm

Thank you for this article about Native American sky atlases. I forwarded the link to our Kentucky Heritage Native American consultant. I received a note of appreciation.

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

USA

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.