These days you can dabble in all kinds of citizen-science activities — y'know, the ones that let you sift through massive observational databases in the hope of finding something scientifically important. But how about one that directly pits humans against computers in a quest to find worlds around other stars? That's what awaits participants in Planet Hunters, the latest offering from the good folks at Zooniverse.

Astronomers detect a planet transit by monitoring the light of a star over a long period. If the brightness dips down, it is likely caused by the passing shadow of an orbiting planet. This effect only works when we are directly in line with the plane of the exoplanets orbit in relation to the star.

Here's the concept. Right now NASA's Kepler spacecraft is staring at a patch of sky covering 105 square degrees near the Cygnus-Lyra border, continually streaming its observations back to Earth. Then computers comb through the data looking for a temporary dip in the light from one of the estimated 100,000 stars in the search field. If those little dips create a repetitive pattern, an algorithm will flag it as a planet that periodically transits (passes in front of) its star. The depth and timing of these dips give Kepler scientists enough information to deduce the size of both the planet and its orbit.

It's a simple strategy, but it's not foolproof. "The human brain is particularly good at discerning patterns or aberrations," the Planet Hunters team explains. "While we expect computer programs to robustly identify things that they are trained to find, we are betting that there will be a number of surprises in the data that the computer algorithms will miss."

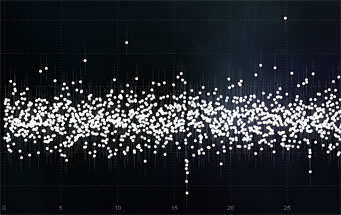

This plot of Kepler spacecraft data shows a star's brightness over time. Besides normal scatter, the light curve exhibits repetitive single-point dips that might signal the presence of a planet periodically passing in front of the star.

Planet Hunters / Zooniverse

So, are you better at pattern recognition than a NASA computer? "This is a gamble, a bet if you will, on the ability of humans to beat machines just occasionally," notes the website. "It may be that no new planets are found or that computers have the job down to a fine art. And yet, it's just possible that you might be the first to know that a star somewhere out there in the Milky Way has a companion, just as our Sun does."

The Planet Hunters team keeps track of the extrasolar planets already found by Kepler. If you've flagged a possible transit event for something not on that list, and if other Planet Hunters flag the same data, the science team will investigate. Strong candidates will get spectroscopic scrutiny from one of the Keck telescopes in Hawaii. And if it's really real, the Planet Hunters who discover the new transiting planet will be included as co-authors on scientific papers submitted for publication.

I can't imagine that you wouldn't want to have your name forever linked to the discovery of a new planet thousands of light-years from Earth. But if planet-hunting isn't your thing, plenty of other projects are vying for your eyes or your computer's processor. For example, you might fancy looking for glowing bubbles in the Milky Way, or keeping a storm watch for eruptions on the Sun. Zooniverse is running three different efforts to identify distant, primordial galaxies, along with an effort to identify lunar features. Of course, you can always latch onto the granddaddy of citizen-science projects, SETI@home.

As for me, I'm hoping someone will launch an effort to track purchases of new telescope hardware. Plot those data on a world map, and you'll know exactly where the skies are cloudy at any given moment.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.