The gravitational wave observatory has detected a second event, heralding a new era in astrophysics.

S. Ossokine / A. Buonanno / T. Dietrich / R. Haas / Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics / the Simulating eXtreme Spacetime (SXS) project

The day after Christmas last year, the cosmos quietly gifted scientists with gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of spacetime – produced in a collision between two stellar-mass black holes. It’s the second event detected by physicists working with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), and it suggests that after some fine-tuning LIGO will be spotting dozens of these events each year.

The first discovery, detected last September and announced this February, was an astounding achievement for science, another piece of evidence proving Einstein’s general theory of relativity correct and, moreover, throwing open a new window on the cosmos. It ushered in an era where astronomers can use gravitational waves to detect black holes previously hidden from view. At the time, LIGO Executive Director David Reitze called it a “scientific moonshot.”

A Second Landing

And the second event is no less remarkable. The two black holes, which weighed in at roughly 7.5 and 14.2 times the mass of the sun, had been circling each other for eons before they finally crashed together 1.4 billion years ago. The bang was so furious — with energy equivalent to the entire mass of the sun — that it sent shudders across the universe.

As those gravitational waves rippled through the universe, they stretched and squeezed the fabric of space-time by an exceedingly tiny amount. At the LIGO detectors, for example, they distorted space-time by as much as three parts in 1022. “That's like changing the distance between the earth and the sun by a fraction of an atomic diameter,” says Gabriela Gonzalez (Louisiana State University), chair of the LIGO collaboration, in a much-anticipated press conference yesterday at the American Astronomical Society meeting in San Diego.

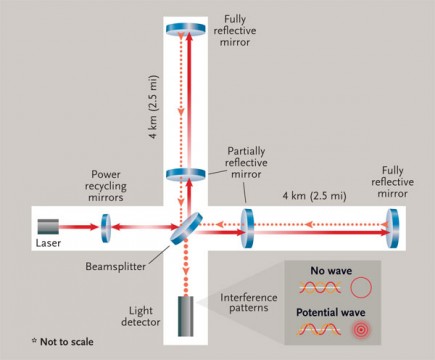

S&T: Leah Tiscione

LIGO can detect such a miniscule distortion with the help of two laser beams that bounce between mirrors at the opposite ends of 4-kilometer-long vacuum pipes. As the gravitational waves pass through the detector, they cause the length of one of the pipes to shorten or expand, forcing that pipe’s laser beam to arrive a fraction of a second before or after the other pipe’s.

In December, this allowed scientists to detect a wave whose oscillation began at 35 cycles per second (hertz) and rapidly increased to 450 hertz. When converted to an audible sound, the wave makes an unmistakable chirp. “This is what we call gravity's music,” says Gonzalez. And the first chirp took the world by storm.

But the two chirps detected so far are not quite identical, revealing vast differences between the two fender benders that produced them. The first signal LIGO spied radiated outward from two surprisingly heavy stellar-mass black holes. As such the chirp was loud but short. It lasted only 0.2 seconds and allowed scientists to glimpse the last 10 cycles of the black holes’ orbits before their collision. But the latest signal radiated outward from two lighter black holes. This chirp was weak, barely visible above the noise, but long. It lasted a full second and allowed scientists to witness the last 55 orbits of the black holes’ inspiral.

“The first LIGO detection was a whopping huge signal from improbably large, merging black holes,” says Chiara Mingarelli, a gravitational wave astronomer from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who is not a part of the LIGO collaboration. “This second signal tells us more about the [typical] population of black holes in the local universe.”

The latest result also suggests that one of the black holes was spinning at roughly 20 percent of the maximum theoretical spin rate for a black hole. “A measurement of the binary black hole’s spin can serve as an indicator, or tracer, of how the binary came to be and how it evolved,” says Mingarelli. “A binary that formed in a relatively isolated system is expected to have aligned spins, whereas if the binary formed in a dense environment, one would expect the spins to be misaligned.” Thus, future detections should relay the black holes’ surroundings and hint as to how they formed.

A New Era

Perhaps more importantly, the second observation shows that LIGO has only just begun. “The future is going to be full of binary black hole mergers from LIGO,” says Reitze. “We're going to see a lot more of these as we go forward.”

The next run, which begins in the fall, will increase its sensitivity by 15 to 25 percent. Given that the last four-month run resulted in two mergers, Reitze expects that the added sensitivity will result in six to eight mergers over the six-month run. That’s important because researchers would like to collect enough findings to study the frequency of black hole collisions across the universe. (The team also observed an additional event in the first run that was too weak to confirm.)

Physicists hope that LIGO will eventually detect gravitational waves from other, fainter, types of cosmic collisions, like those between neutron stars. These events are expected to both trigger gravitational waves and emit electromagnetic radiation. A detection of both could allow astronomers to better understand such wild events. But first, physicists need to pinpoint them on the sky. More gravitational-wave detectors coming online in the coming years, including one in Italy and two in India, will help scientists do just that.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, the second detection alone is still an event to marvel at. “With this, we can tell you now that the era of gravitational wave astronomy has begun,” says Gonzalez.

Reference:

B. P. Abbott et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and VIRGO Collaboration) “GW151226: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a 22-Solar-Mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence.” Physical Review Letters. June 15, 2016.

10

10

Comments

Chris-Anderson

June 16, 2016 at 4:16 pm

"At the LIGO detectors, for example, they distorted space-time by as much as three parts in 1022."

That should be three parts in 10^22, or 3 parts in 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chris-Anderson

June 16, 2016 at 5:02 pm

Also, the detection came on the day after Christmas, not the day before (Christmas Eve).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica Young

June 17, 2016 at 11:55 am

Thanks for the catch, Chris, I've updated the text. I do see the exponent (10^22) showing correctly in the text though.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

flybd5

June 17, 2016 at 4:24 pm

I'm curious... isn't this "detection" something that is triggered by a computer matching the detector data what people -think- the data -should- look like for a black hole merger, and has there been any physical correlation of data to an event recorded with some other form of detection mechanism?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stephenano

June 17, 2016 at 7:58 pm

Fascinating observation and remarkable achievement in signal extraction and interpretation. I thought that the comment that "three parts in 10^22 ... is like changing the distance between the earth and the sun by a fraction of an atomic diameter,” might be one of those 'throw-away lines' but actually it is about one eighth the diameter of a carbon atom! Assuming the amplitude falls as the square of the distance, the same event in Andromeda (at 2.5 mly) would stretch the sun-earth distance by about 13 um or about an eighth the diameter of a human hair - still not enough to rattle the crockery! One question - the graphic illustrates the propagating GW as being a 2D plane wave, implying that the observer would need to be in the plane of the orbiting black holes to detect it. Is that correct?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

June 18, 2016 at 6:22 am

I'm not sure if you understand what LIGO is. It is the instrument for *directly* detecting gravitational wave (GW) by detecting actual changes in space, as in detecting contraction/expansion of space itself, as a function of time, as predicted by Einstein's General Relativity. How much more direct can you get than that in terms of GW detection? And when the data match was found, that was based on actual mathematical prediction via Einstein's GW field equations. The detected data matched the prediction to a high degree of numerical precision. In a physical world that is filled with random processes, this is astounding. In other words, the probability that it is something else other than a GW is extremely small. So how else would you detect GW waves? What other forms of detection did you have in mind?

From Wikipedia: "LIGO's mission is to directly observe gravitational waves of cosmic origin."

Note the words "directly observe".

ESA's LISA project aims to detect GW using the same detection principle. So I don't know what other forms detection you were thinking of.

Just as optical telescopes are instruments for detecting visible light EM waves and radio telescopes are instruments for detecting RF EM waves, LIGO and other similar devices are instruments for detecting GW. GW is another realm that is separate from EM waves and provides a new window for observing and understanding the universe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

June 18, 2016 at 6:33 am

Correction: GW field equations should be GR (General Relativity) field equations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

June 18, 2016 at 1:25 pm

I assume we can trust the reliability of the LIGO detectors -- they directly observed gravitational waves. flybd5's question regards how those gravitational waves were used to infer that they were caused by merging black holes, and the distance and sizes of the black holes.

(By the way, it is easier and more pleasant to converse with people who use their real names.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

June 25, 2016 at 4:20 am

The fermi gamma-ray detection space telescope may have observed an event which coincides with the first gravitational wave detection by LIGO. There's an April 21 2016 article about it by the same author (Shannon Hall)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wayne H. Warren Jr

June 17, 2016 at 5:29 pm

Note to Shannon:

Nice article on the LIGO project. In your second paragraph you discuss evidence "proving" Einstein's

GR. However, the word should be "confirming". Remember that nothing is ever proved in science, only disproved. A future observation can always disprove a scientific theory.

Dr. Wayne H. Warren Jr.

[email protected]

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.