It's time again for the Geminids, one of the year's best meteor showers. There'll be interference from moonlight this year, but you'll still probably see plenty of these "shooting stars."

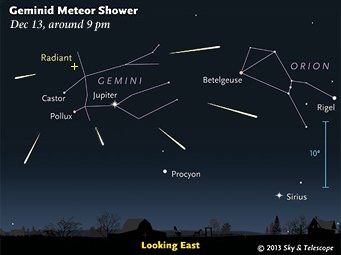

Although they can appear anywhere in the night sky, Geminid meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini, which is well above the horizon by late evening.

Sky & Telesope diagram

In mid-December every year Earth passes through the Geminid meteoroid stream. The resulting meteor shower is unusual in several ways. It's often the richest reliable shower of the year, and it seems to be strengthening over the decades. It becomes nicely active as early as mid-evening, so you don't have to wait until after midnight (as is the case with many other showers). Its meteors are relatively slow, arriving at 36 km (22 miles) per second, hardly more than half the speed of the Perseids, Orionids, and Leonids. Also, these meteors often appear yellowish, and their deep plunges into the atmosphere betray them as dense bits of rock rather than fluffy dust clods like most cometary meteors.

And in fact they come not from a comet but a tiny asteroid, 3200 Phaethon, that is itself an oddball. It's in a tight, highly elliptical orbit that, every 1.43-years, brings it three times closer to the Sun than Mercury's average distance. So the Sun repeatedly shines on it 50 times brighter than sunlight on Earth.

This year the Geminid shower should peak around 6h Universal Time (1 a.m. Eastern Standard Time) on Saturday, December 14th — ideal for North Americans, especially easterners. But the waxing gibbous Moon will be bright, three days from full and shining most of the night. The Moon sets one hour before the first glimmer of dawn on the morning of the 14th, affording a nice dark window for serious meteor observers.

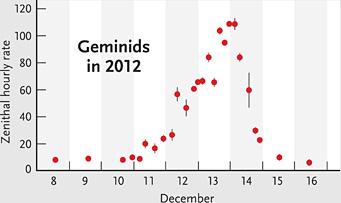

Last year's Geminid shower behaved normally, peaking at a rate of more than 100 meteors per hour. The zenithal hourly rate is the number of meteors that a single observer would see per hour under ideal conditions (for example, without any interference from moonlight or light pollution).

International Meteor Organization

The shower is also active for a few days before then, and the Moon sets about an hour earlier for each day before the 14th. The Geminids drop off more steeply after maximum, as seen in last year's activity profile at right.

Bundle up as warmly as you can. Find a spot with an open view of the sky and no lights to get in your eye. Lie back in a lawn chair facing away from the Moon, gaze into the stars, and be patient. You might see a Geminid every minute or two on average depending on the brightness of your sky. The shower's radiant point is in Gemini near Castor, and the higher that is the better, but the meteors themselves will appear anywhere in the sky. So watch wherever it's darkest.

What exactly creates the Geminid meteoroid stream? Small-body researchers David Jewett and Jing Li (UCLA) say they've figured it out. Astronomers have thought that the stream's parent body, 3200 Phaethon - discovered in 1983 and only 5 km (3 miles) wide — must be a dead comet nucleus. During its loops around the Sun every 17 months its surface roasts to more than 700°C (1300°F), and all water and other volatiles must have been baked out ages ago. So then, how can it shed any particles at all?

Jewett and Li found proof that it still does. NASA's two STEREO spacecraft, designed to observe the Sun, are also able to see Phaethon when it's nearest the Sun despite its tiny size. STEREO images show that Phaethon brightens and sheds a dust tail when it's in the most intense heat. With no volatiles left to vaporize and carry dust away, the two astronomers propose that Phaethon's bare rock cracks and crumbles by thermal fracturing. Jewett calls Phaethon a "rock comet."

During the 2004 Geminid meteor shower, Alan Dyer caught a bright fireball with a tripod-mounted digital camera. He used a wide-field, 16-mm lens for a 1-minute exposure at f/2.8 with an ISO setting of 800. Expect to shoot a lot of frames before you get this lucky. Click image for larger view.

Alan Dyer

"While this is the first time that thermal disintegration has been found to play an important role in the solar system," the two write, "astronomers have detected unexpected amounts of hot dust around some nearby stars that might have been similarly produced." So count it as another way the Geminids are unusual.

Become a Meteor Counter

Have you ever done a scientific meteor count? The International Meteor Organization always wants more observers around the globe. You'll need to follow the IMO's standardized instructions so that your counts can be meaningfully compared with others. See the IMO's website and also our site's introduction to advanced meteor observing.

2

2

Comments

Steven Lewis

December 13, 2013 at 8:15 pm

Time 23:30. Location: The Chew Valley, Somerset, UK.

I wandered out across the fields alone, below grey skies, not holding out much hope. It had rained most of the afternoon and was still damp and chilly. I had taken up position on a bench I know, by the side of a footpath, which gives an excellent command of all horizons, and waited patiently. A Vixen was sceaming, a little spookily, off to my south and Tawny Owls called to each other. By 00:15 the clouds began to break, but I was cold and beginning to lose my resolve. Another 15 minutes passed and clear patches of stars appeared through the grey, yet still no sign. I sighed, and made an effort to stand when I heard it...Boom!...Fizzzzz...I hastely looked up and witnessed my first long duration, bright green Geminid meteor punch through the cloud. Yes!

Miracle of miracles. The cloud cleared rapidly and several more streaked through in quick succession. By 01:30 it had turned into a completely cloud free night, much colder, with a waxing Moon to the west of Orion, with Sirius and Jupiter blazing away. The Moon of course spoiled the view of the smaller meteors. But what a night! I lost count after 160 Geminids. Most of which streaked right across the sky leaving green trails behind them, amongst the best I have ever seen.

So, so glad I made the effort. Sorry for those who missed it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Albert & Nancy Foster

December 14, 2013 at 6:34 am

Steven's comments are well written. Our experience has similar elements, but not nearly such success with the meteor count due to a weather front that shut us out completely after a little over an hour. We began about 10:30 pm EST, from our high bluff-top home above Lake Blackshear in southern Georgia, USA. Light, hazy clouds were building in from the south & west. The moon was bright behind us as we set up our chairs facing northeast. The haze had produced a halo around the moon that encompassed at least 50 degrees of the sky above us. Our first Geminid was almost a double of the magnificent shot Alan Dyer captured in the article above. Ours was visible as we watched generally to the north, and almost reached the halo of the moon. It covered perhaps 30 degrees or more of sky with its bright, visible trail. True to Alan MacRoberts' predictions in this article we were able to see well enough by simply facing away from the moon to overcome the light. We were truly pleased that the clouds building in from the south and west did not completely shut down our viewing. Our last sighting, before the forming clouds shut us down completely, was a particularly bright and long trailed meteor that splashed into view to our right (east) and traveled over at least 100 degrees of the arc of the sky before it finally disappeared to our left (northwest) above heavier clouds that had moved into our view. Along its path we saw its intensity vary from very bright to dim to disappeared, and back into view several times as it passed above obviously patchy cloud formations. The effect was unlike any we had ever seen. That must have been a truly incredible meteor had there been no clouds obscuring our view. To us the moral of the night was don't give up due to a few clouds forming. We too would say sorry for those who missed it!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.