The orbital positions of more than a dozen small moonlets around Jupiter and Saturn are so uncertain that they are effectively lost.

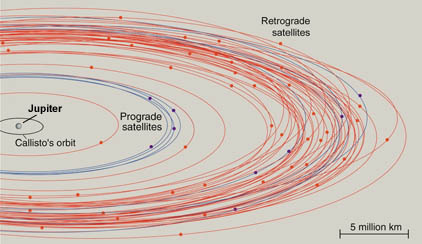

Prior to the year 2000, Jupiter had 17 known moons, about half of which moved in "irregular" orbits that were highly inclined and eccentric and often traveling in reverse (retrograde), with respect to Jupiter's spin. Saturn had 18 moons in all, though only Phoebe occupied an unusual orbit.

Jupiter's irregulars had paths that seemed to be clustered, suggesting that these bodies were related — most likely chunks set loose during long-ago collisions.

Discovery images, taken in 2001, of a 22.1-magnitude moonlet around Jupiter that's just 2½ miles (4 km) across. Spotted as part of a survey for new Jovian moons, this one — later named Hermippe — didn't get away. But some of its siblings are now considered lost.

S. Sheppard / D. Jewitt

To track down more members of these oddball families, University of Hawaii graduate student Scott Sheppard and his adviser, David Jewitt, started an ambitious project to find new irregular satellites around Jupiter and Saturn. Using the big guns on Mauna Kea — first the university's 2.2-m reflector and the 3.6-m Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, and later the 8.2-m Subaru telescope, Sheppard and Jewitt were wildly successful. In a single 2003 article, they announced the discovery of 23 irregular Jovian satellites, clustered into five distinct dynamical groups.

Meanwhile, another observing group, led by Canadian astronomers Brett Gladman and JJ Kavelaars, had likewise been quite successful tracking down new outer-planet satellites, particularly around Saturn. NASA's Cassini orbiter also chipped in a few Saturnian moonlets after its arrival in late 2004.

[caption id="attachment_9444" align="alignright

7

7

Comments

Joshua Barnes

April 6, 2012 at 12:39 am

"To lose one moon, Mr Jewitt, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose ten looks like carelessness." (With apologies to Oscar Wilde)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Emilio Pisanty

April 6, 2012 at 7:20 am

Are these moons simply lost, in that we don't know where they are, or is there the possibility that they may have been kicked out of their systems? Were their orbits known precisely enough beforehand to rule out this possibility?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

April 6, 2012 at 2:43 pm

The list of names of satellite, asteroids, and dwarf planets, with their discovers, dates and places of discovery, and the mythological meanings of their names at http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/Planets#JovianSystem is simply fascinating. It absorbed a significant part of my lunch hour! I especially enjoyed the moons of Uranus.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ed

April 6, 2012 at 7:31 pm

Hi Emilio, Good question. Although the is a very small possiblility that these little guys are gone, it is WAY more likely that thay are still there if they exist. Like the article says, you really need to pin down an orbit to know where to look to reaquire them for a "real" discovery. There are some tiny moons that I'm sure get captured by Jupiter, stay for a few million years, nudged out of orbit, meander around in a similar Jovian orbit for while and maybe even get recaptured. They are in orbits that are quite far away for Jupiter, and would be in this sort of "dance" more than really being able to be "kicked out" in a more violent way. On the way back into the Jovian system, they could be kicked out into a solar orbit, but then they wouldn't of been a moon at that point. So what is comes down to is the odds of something like that happening in the few years since we "lost" them. It's possible, but highly likely. Ed

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John F. Tashjian

April 7, 2012 at 10:59 am

I know that the explanation was given in the article, but it still begs the question: how on Earth (so to speak) can a planet's moon become "lost" once it has been observed? I'll concede that some moons' orbits are quite irregular, but I cannot imagine how such moons can be lost...unless, of course, they fell out of orbit. Something to reflect on, and to think about, I suppose.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

darvasart

April 7, 2012 at 1:19 pm

any possibility that some of these moonlets with fringe orbits go "loose" ... join another planet or even go into a solar orbit .. then return.. in some figure 8 or more complex path .. that may give argument for retrograde orbits .. some of these patterns could take millions of years to repeat?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

April 8, 2012 at 9:57 am

As various reports like "Irregular Satellites of the Giant Planets", Publication Date: 00/2008, http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008ssbn.book..411N indicate, explaining the origin of the irregular moons of the giant planets is difficult. If we do not truly know how they formed then the question rises, when did the irregular moons form? Are the irregular moons evidence of past catastrophism in the solar system, e.g. < 1E+8 years ago?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.