The annual Perseid meteor shower peaks this weekend, providing skywatchers with a great opportunity to see some incoming bits of the cosmos.

I'm nearing the end of my time at S&T. The last few months have been entertaining and educational, and I've greatly enjoyed my internship in the amateur astronomy community. My wife and I will point the truck west on Saturday morning, and by Saturday evening we should be at a small hotel in central Pennsylvania. We picked the spot because it's about as far from city lights as the Interstate system will comfortably allow.

Amateur astronomer Fred Bruenjes arranged this composite image of the 2007 Perseids from nearly 3000 images taken over two nights. The picture clearly illustrates that the Perseids originate from the same area. (Note again that this is a composite image; don't expect to see this many meteors at once.) Click for a larger view.

Fred Bruenjes

Our plan for that night is to find a field, spread a blanket on the ground, and watch the Perseid meteor shower. It's actually going on right now — it started in mid-July and will continue until late August — but the show will reach its peak from late on the 11th through the early hours of the 12th. It probably won't be the year's most spectacular display; most years, that honor goes to the December Geminids. But the Perseids are almost certainly the most-watched meteor shower, coming as they do in the warm, vacationing months of late summer.

Watch SkyWeek and take a tour of the Perseid meteor shower.

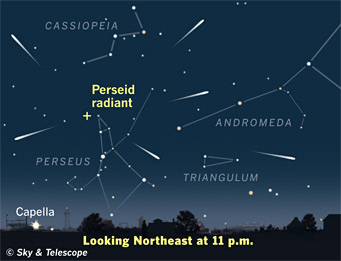

The Perseid meteors appear to stream away from the shower's "radiant" point near the border of Perseus and Cassiopeia. Under dark-sky conditions, you may see an average of one a minute around the time of the shower's peak.

Sky & Telescope illustration

Like all meteor showers, the Perseids are named for the constellation from which they appear to radiate. Perseus will hang low in the northeast early on the night of the 11th. The shower will really get underway after 11 or midnight local time, when from a dark site you may be able to spot one or perhaps two Perseids a minute on average. The rate should increase as Perseus gains altitude in the early hours of the 12th, though a thick waning crescent Moon will rise around 1 or 2 a.m. The International Meteor Organization says that the Moon's modest light that night "should be considered more of a nuisance than a deterrent." For the next three nights the shrinking crescent will rise an hour later per night, and from the 16th on it will be gone.

Although the Perseids are named for Perseus, the constellation obviously has nothing to do with where the meteors were born. Most meteors come from comets shedding dust and debris as they travel through our region of the solar system. We see a shower when Earth, in its annual travels around the Sun, passes through a meteoroid stream strung along a comet’s orbit. It’s only from this perspective that we see the Perseids appearing to come from Perseus.

And that’s if you trace their paths backward far enough across the sky. The meteors can flash into view anywhere in the sky as long as Perseus is above the horizon. So the best part of the sky to watch is wherever is darkest, probably straight up.

Space-station astronaut Ron Garan captured a dramatic Perseid meteor against Earth's moonlit clouds on August 13, 2011.

Ron Garan / NASA

The Perseids are pieces of Periodic Comet Swift-Tuttle. As Earth passes near the comet's orbit, tiny chunks of debris — mostly the size of grains of sand, but some as large as peas or bigger — enter the atmosphere at 60 km per second (134,000 mph). Starting at an altitude of about 100 km (60 miles), a meteoroid compresses the air in front of it like water before a speedboat, creating a white-hot shock wave. This is what you mostly see — not the little bit of debris itself.

Meteors that come from comets are more like dust clumps than rocks. Even big ones are too fragile to make it down to the ground as meteorites — unlike pieces of rock and iron, which come from asteroids.

Earth passed closest to Comet Swift-Tuttle in 1992, and the Perseids put on particularly spectacular displays during the years around then. The shower has since returned to normal. The comet won't approach so close again until around 2125, but that doesn't mean this year's Perseids won't be worth finding your own patch of dark sky. Try to get as far from city lights as possible, bring a reclining lawn chair to lie back in, and be patient. Telescopes and binoculars restrict your field of view too much for meteor-watching; for this your naked eyes work best.

I've had fun covering amateur astronomy this summer, and I'll be happy to go out amid a field of shooting stars. I hope you enjoy the show. I know I will.

----------------

Addendum: If you're going to be watching the show anyway, why not use the opportunity to make a contribution to science? The easy-to-use MeteorCounter app for iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch allows you to report your Perseid sightings directly to NASA scientists, who will use your data in their research. Learn more at the MeteorCounter website, or search for the app on the App Store.

5

5

Comments

Bruce

August 10, 2012 at 1:27 am

I've really enjoyed your writing Stephen and I'm disapointed to read that your time with S&T is coming to an end. I wish you well in your next endevours.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stephen Craft

August 10, 2012 at 11:38 am

Thanks for the well-wishes, Bruce. It's been a fun summer and I'm a little sad myself, but I hope to continue to contribute to the magazine whenever I can. Thanks again!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tom J

August 10, 2012 at 12:05 pm

When you stop in PA, if you're close try to get to Cherry Springs State Park. About as dark a sky as you can get around here and they are astronomy friendly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

August 10, 2012 at 1:30 pm

Best wishes, Stephen. I look forward to seeing your byline in Sky and Telescope in the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John F. Tashjian

August 11, 2012 at 9:41 am

I never did like long "goodbye"s, so I'll keep this brief: I wish you much success in all your future endeavors...Keep looking up!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.