Is perception reality? Not when it comes to the Moon illusion. See the truth with your own eyes at the rising of the next full Moon.

Bob King

Watch for the full Frost Moon to rise around sunset Wednesday night (November 25th), a perfect opportunity to witness one of the oldest psychological tricks known to humankind: the Moon illusion.

Even as far back as the 4th century B.C., Aristotle noted the apparent hugeness of the horizon-hugging Moon compared to it viewed overhead. Back then, it was attributed to magnification by the atmosphere, but now we know the Moon illusion all in our head. Photos of the rising and meridian moons show them as identical in size.

To see for yourself, take a sheet of paper and roll it up into a narrow tube. Point it at the rising Moon and adjust the tube's size until it's a little larger than the Moon's diameter. Tape the tube so its size stays the same and look at the Moon again a few hours later when it's higher in the sky. You'll see it fills the same space.

The Moon illusion not only applies to the Moon but also to the constellations. Many observers have noticed this when viewing constellations near setting or rising compared to mental images of those same groups viewed higher up. Just the other night I caught sight of the trapezoid-shaped "Keystone" of Hercules setting in the northwest. It was huge! That was my first impression, but interestingly, the sensation faded the longer I looked.

Stellarium

The Big Dipper offers one of the best examples of constellation inflation, a phenomenon you can easily see this month and next. During early evening hours, the Dipper looms large as it arcs along the northern horizon, but seems to shrink toward dawn on its climb toward the zenith.

For as long as we've seen the Moon illusion, people have been trying to explain why it happens. There's no question it has to do with how we perceive celestial objects in a terrestrial setting, but the particulars remain elusive. So what's going on here?

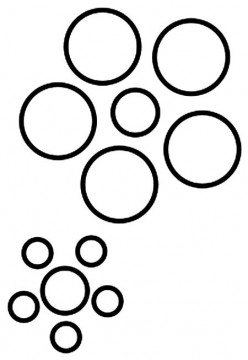

In daily experience, an object overhead, say a bird or aircraft flying by, appears closer and therefore larger than the same bird or plane near the horizon because it really is closer. We're built to think that objects near the horizon are (usually) more distant than those overhead because they appear to lie behind and beyond foreground objects.

Bob King

But for extraterrestrial bodies such as the Moon, Sun and star groupings, which are identical in size whether on the horizon or at the zenith, we have no reference. Therefore, when we gaze at a horizon Moon, which clearly lies beyond every object in the foreground, our brains assume it must be farther away than the overhead version. We compensate for this perception by inflating the Moon's size. In a sense, our brains force the Moon to meet our expectations of how big it should be.

Göran Strand

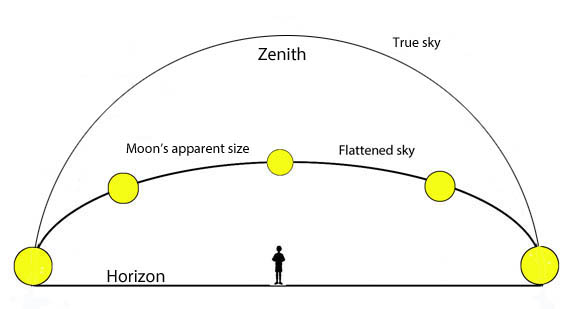

This perception is reinforced by yet another perception — how we see the shape of sky. Lots of us look up and imagine the sky as a flattened dome with the zenith relatively nearby and the horizon in the far distance. Our mental muscle miscalculates the Moon's distance, imagining it to be much farther off compared to its overhead distance, which brings us back to the size-forcing issue. The flattened sky perception may help explain why some airline pilots report seeing a bloated, low Moon in an empty sky with no reference but the horizon.

AlexWorth91 / Wikipedia

Our brains happily create powerful illusions from the moment we wake up in the morning. Think of all the rectangular and square objects we come across during the day. Unless you're staring square-on at these shapes, they should look like trapezoids of all dimensions. Do they? No — our brains still see them as squares and rectangles even when viewed up close from the side. Crazy!

What's funny in all of this is that the rising Moon is actually 1.5% smaller than when it's overhead because we have to look across the radius of the Earth — or just under 4,000 miles — at rising time. With the Moon near the zenith, we look straight into space with no Earth in the way. Perhaps the solution to the illusion lies in a mashup of perceived distance, our internal model of the sky, and the Ponzo illusion.

Other explanations abound, proving that a complete solution remains a moving target. Take a look for yourself the next few nights when the frosty Moon climbs above the eastern horizon.

Find a spot with a busy foreground and compare that impression to one made in a simpler setting where you can easily block out the foreground to show an isolated Moon relatively close to the horizon. Do both perspectives swell the Moon's apparent size equally? Then look at the Moon when it's high in the sky and recall its rising appearance. Does it look obviously smaller?

Rick Baldridge

Whether you perform these simple experiments or just feel like basking in the brilliance of the November Moon, click here for moonrise times for your location. And don't forget to watch the full Moon occult Aldebaran early Thanksgiving morning (November 26, 2015) across much of the U.S. and Canada. It occurs around 4:30 a.m. CST (5:30 EST, 3:30 MST and 2:30 PST). Talk about illusions. You'll be watching the puny 2,160-mile-diameter Moon cover a star nearly 18,000 times its size.

Need a map to go with that Moon (and potential Moon illusion)? Check out the Sky & Telescope Field Map of the Moon!

9

9

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

November 24, 2015 at 3:30 pm

From my home in San Francisco, the eastern horizon is the ridge of Potrero Hill only about a mile distant. When I see the Moon rising above Potrero Hill, she doesn't look especially big. But if I walk up to the top of Bernal Hill, I can see all the way across the bay to the east bay hills, about 20 miles away. The Moon rising over the east bay hills looks huge!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dale Lehman

November 24, 2015 at 11:55 pm

Strangely, I don't think I've ever seen the moon as unusually large when near the horizon. I have sometimes tried to figure out whether or not it looks larger near the horizon, but it never really does. I have no idea what that means . . .

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don-Weiss

November 27, 2015 at 7:27 pm

Oops! You shouldn't have chosen that particular image of the Big Dipper to illustrate your point. It was taken with a very wide angle lens. As a result, the length of the dipper in the lower part of the photo is 4 cm but in the upper part of the photo is's 2.9 cm -- at least on my monitor.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ROBERT STENTON

November 28, 2015 at 12:07 am

If you ever have seen the old moon in the arms of the new moon, the crescent moon appears much larger than the new moon which is made visible by dim Earth-shine. This enlargement is due to the neurological phenomena of "recruitment". The brighter image (the crescent) essentially spreads out into neighboring neurons. You can tell this is happening because the spreading out also blurs the brighter image. Recruitment works best if some neural activity is already present in the neighboring neurons since less needs to happen to those neurons to get them to fire. So when are neighboring neurons most active? For a full moon it occurs exactly at moon-rise and moon-set when the sky is still somewhat illuminated by the rising and setting sun or when a near-by passing cloud is illuminated by the full moon itself. When does it happen least? When the moon is high in a totally black sky. This explanation does not mean there is not also an accompanying optical illusion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

November 28, 2015 at 9:01 am

As a pilot, I have noted that the sun, very low on the 'nearby' horizon before takeoff, appears to be its usual 'enlarged' self, and as one ascends to an altitude of several thousand feet over a few minutes, and the actual horizon shifts to tens of miles away, the sun's apparent size reduces greatly. (One can also watch the sun set twice--once while holding for take off on the ground, followed by the reappearance of the full orb on climb out, and then, when at level flight, watch it set again behind that now more distant horizon).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

November 29, 2015 at 10:20 pm

Thanks Robert for your comments about 'recruitment'. I think I have also heard the effect called irradiation, too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kim-Boriskin

November 28, 2015 at 10:19 am

The comparison to foreground objects idea isn't the whole explanation, and maybe isn't correct at all. For example, the moon appears large even when viewed on the open ocean, where there are no comparison objects. And you can make the illusion disappear very simply. If you don't mind looking a little foolish, bend over and look at the moon between your legs. It looks normal size.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

November 29, 2015 at 1:12 am

Apart from the convergence of lines to horizon the more commonly experienced cloud deck has primed us to perceive clouds near horizon further away than clouds overhead. We have been so conditioned by this experience since birth that even in a cloudless sky it is virtually impossible to dissuade oneself from enlarging celestial objects near the horizon to compensate.

Martin Lewicki

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ERROR404

December 27, 2020 at 2:30 pm

i was in my house and the moon rised up so big it looked bigger than the sun

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.