From its dynamic atmosphere to its hidden depths, Juno reveals Jupiter as never before.

NASA

Forget what you thought you knew about Jupiter. The first science results are in from NASA's Juno spacecraft, currently in orbit around Jove. The findings were published in this week's Science and Geophysical Research Letters today, along with a salvo of press releases.

For starters, there was this eye-popping, never-before-seen sequence of Jupiter's aurorae, captured by Juno's Ultraviolet Spectrograph. The long-tailed "comet" on the left is the footprint of an electromagnetic connection to the moon Io:

Juno's orbit takes it around Jupiter once every 53 days, from a perijove 2,500 miles (4,000 km) above the Jovian cloud tops, to a five million mile (8 million km) apojove out past the orbit of Callisto. Original plans called for Juno to enter a tighter, 14-day-long orbit around Jupiter, but NASA decided to keep Juno in its present initial capture orbit after a helium valve engine anomaly turned up during a course correction burn last October. Juno will complete eight more planned orbits and was granted a brief reprieve as its final disposal via atmospheric entry won't occur now until July 2018.

Comparing Gas Giants

It has been a thrilling ride, as Juno scans Jupiter in detail from pole-to-pole once every pass in a whirlwind six hour science phase. Juno completed its sixth perijove pass earlier this week. Unlike what Cassini is seeing on its Grand Finale orbits around Saturn, however, the poles of Jupiter are chaotic and complex.

NASA / MSSS / SwRI / Gerald Eichstädt / Seán Doran

"We knew, going in, that Jupiter that Jupiter would throw us some curves," says Scott Bolton (Southwest Research Institute) in a NASA press release. "But now that we are here we are finding that Jupiter can throw the heat, as well as knuckleballs and sliders. There is so much going on here that we didn't expect, that we have to take a step back and begin to rethink of this as a whole new Jupiter."

NASA / MSSS / JPL / SwRI / Bjorn Jonsson

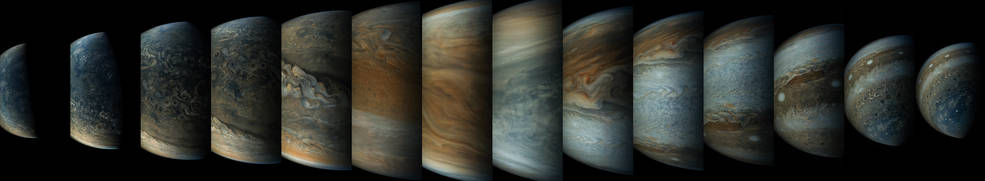

Thus far, Juno has delivered unparalleled views of Jupiter's poles, revealing complex cloud festoons and enigmatic white ovals and cyclones the size of the Earth. Pioneer 11 in 1974 and the Ulysses flyby of Jupiter in 1992 provided the only other polar views of Jupiter, and these were from much greater distances.

Here's a highlight rundown of the first science findings of Juno at Jupiter:

NASA / J.E.P. Connerney et al/Science

Atmosphere: Sounding by Juno's Microwave Radiometer instrument points towards a robust cycling of the ammonia clouds shrouding the planet and an ammonia-based weather cycle extending deep below the cloud tops. This ammonia stream is evident racing around Jupiter's equatorial belt — Jupiter rotates once every 10 hours, the fastest spin of any planet in the solar system — but Juno sees this ammonia belt extending deeper than expected, to a depth of at least 300 km. In fact, the main ammonia-rich plume near the Northern Equatorial Belt resembles a larger version of the Hadley Cell circulation seen in the equatorial regions of the Earth.

Just what powers the swirling storms near Jupiter's poles, and why does the northern pole of the planet differ dramatically from the south? "We're questioning whether this is a dynamic system," Says Bolton in a recent press release. "Are we seeing just one stage, and over the next year, we're going to watch it disappear, or is this a stable configuration and these storms are circulating around one another?"

NASA / JPL / SwRI

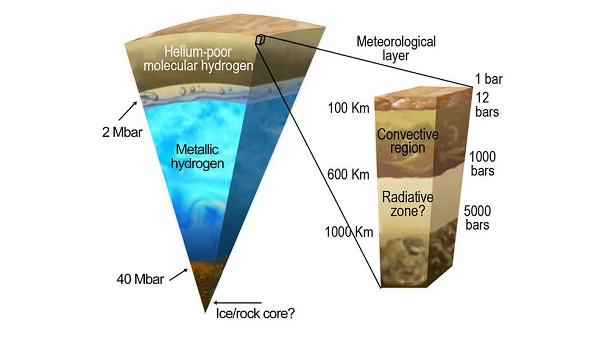

Gravitational field: The orbit of Juno makes it an ideal platform to plumb the extent of Jupiter's gravitational field, giving scientists a chance to understand the interior structure of the planet. By carefully tracking Juno's motion, engineers back on Earth can detect minute changes in the planet's attractive force on the spacecraft.

Previous models featured sharp demarcations between transition layers, with perhaps a metallic liquid hydrogen core enveloping a bizarre high pressure zone of helium precipitation. Juno's preliminary findings, however, challenge this assertion and suggest instead a large but indistinct “fuzzy” core diluted with layers that are intermixing. Understanding whether or not Jupiter has a solid core is a key mystery in planetary formation.

NASA / MSSS / SwRI / Caltech

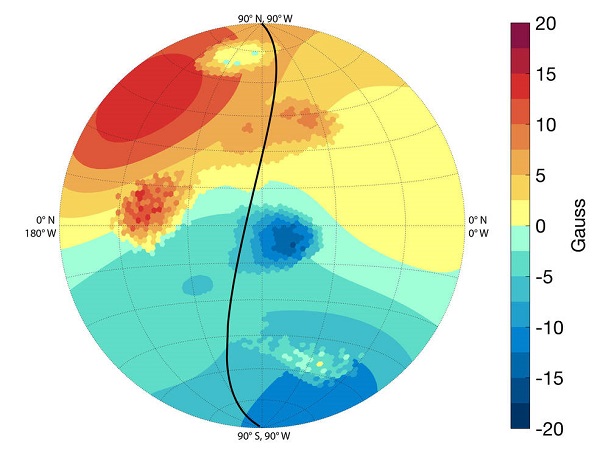

Finally, Juno delivered another surprise. Jupiter's magnetic field is not only almost twice as strong as expected in spots, but it's not uniform. These results come from Juno's magnetometer and microwave radiometer. Specifically, the field strength peaks near 8 to 9 gauss, nearly twice the expected 5 gauss. Earth's magnetic field is a paltry 0.3 to 0.7 gauss: for comparison, a typical refrigerator magnet has a field of about 50 gauss, powerful over short distances. Juno also recorded variances in the magnetic field map surrounding Jupiter up to 2 gauss. This strongly suggests that the dynamo generating the field is relatively shallow, rather than the deep-seated engine driving the magnetic field emanating from Earth's core.

NASA / MSSS / Caltech / SwRI / Roman Tkachenko

Radiation: The mission has provided another unique plus, with spectacular closeups of aurora over both poles of Jupiter. Jovian aurora have been seen by the Hubble Space Telescope orbiting the Earth, and Juno has now chronicled these up close, along with the footprint of the powerful Io flux tube extending from the innermost Galilean moon. JunoCam and Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) are the prime instruments monitoring Jovian aurora.

Thus far, Juno has navigated through the intense radiation field surrounding Jupiter relatively unscathed. The main spacecraft bus is shielded within a sturdy titanium housing.

Juno is the first outer solar system mission powered by three solar panels instead on a plutonium-fueled generator. And those panels are huge, each 29½ feet (9 meters) long. Engineers noticed "flecks of light" traveling across Juno's navigational star camera field of view, which were traced back to micrometeoroid impacts along its three huge solar panels. Like with LISA Pathfinder, researchers soon realized that Juno can also serve as a micrometeoroid detector, the largest ever flown.

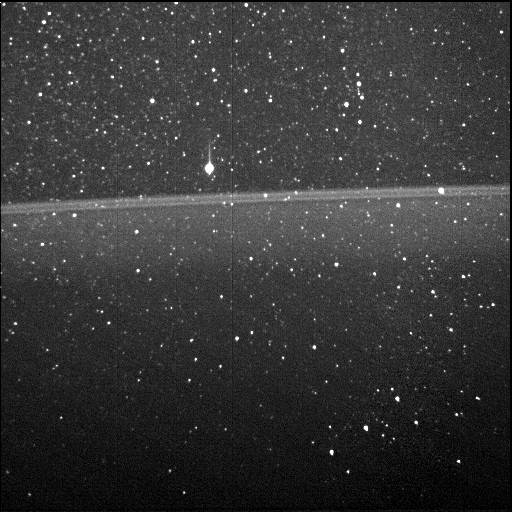

But that's not all that the star trackers saw. Gaze upon the Jovian ring system seen, for the first time, from the planet's perspective:

NASA / MSSS / Caltech / SwRI

More science is sure to come, as researchers analyze Juno data. We've got just over a year remaining to this exciting mission to unravel the secrets of the largest planet in the solar system.

6

6

Comments

Photon Seeker

May 25, 2017 at 7:44 pm

I know everyone must have said that about their own era in the past, but what exciting times to be living in!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

kdconod

May 26, 2017 at 11:23 am

There's some funny math here...last perijove was May 19. End of mission is in July 2018. Not sure of exact date but just for a back-of-the-envelope calculation, the time between May 19 and the end of July 2018 is only enough for 8 orbits. There's no way Juno will reach 33 orbits as mentioned above.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

May 26, 2017 at 3:18 pm

Good catch; 33 was assuming we would be in 14 day science orbits by now, which never happened. Corrected!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob

May 26, 2017 at 11:04 pm

David, thank you for this interesting article on spacecraft Juno lifting the lid on Jupiter's mysteries.

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Roger Venable

May 27, 2017 at 9:10 am

Fascinating stuff!

With regard to the aurora images of Jupiter's South Pole, I note that the South Pole is currently tilted toward Earth by 2.74 degrees. (Jupiter's obliquity is only 3.12 degrees) Thus, the aurora images are in daylight. Were they narrow waveband images? Ultraviolet? Or, is the aurora so bright that it can be imaged in integrated light?

Despite the small obliquity, each pole spends about 6 Earth-years in darkness during the Jovian year. It is reasonable to suspect that the atmospheric circulations at the poles would be somewhat different according to the season of the Jovian year. Is Juno able to make IR images of the North Pole now, while it is not illuminated by the Sun, or are the researchers' comments based only on what they see at the South Pole?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

philip-gardner

June 3, 2017 at 12:51 am

Not being a physicist or space junkie, I wonder if the core of Jupiter is not one of those weirdo asteroid shapes we keep seeing and the rotating magnetic field would be unbalanced, wacking ammonia and other gasses on the way, spitting it out then sucking it back in as it passes every 10 hours? Its a wild ride out there. Great results. Congratulations to all on the Juno project.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.