Five fascinating deep-sky birds nest, fly and dabble along the length of the summer Milky Way. Isn't it time you put them on your life list?

Bob King

The Milky Way has been compared to a river, but it could just as easily be a migratory bird flyway. Seen from the northern hemisphere, the band's slant from northeast to southwest neatly parallels the preferred flight path of many a feathered fowl each fall.

In July, birds stay put. Why leave when the weather's nice, food abundant and you've a family to raise? Like their namesakes, a handful of celestial birds make their homes in the Milky Way. They've built nests in a manner of speaking, ones we might quietly approach on dark nights to see whether eggs have been laid or to check on how the hatchlings are getting along.

I've come across five different summertime species while rummaging across the sky: a parrot, pelican, duck, eagle and swan. If they're not already on your life list, we'll help you to spot them with maps and directions.

Parrot's Head Nebula (B87)

Tenho Tuomi

Most wild parrots live in warm regions of the Southern Hemisphere, and this one's no exception, making its home at declination 32°S within the billowy star clouds of western Sagittarius. Also known as B87 from American astronomer E.E. Barnard's Catalog of Dark Markings in the Sky, this dark nebula is a nice, low magnification object 12′ across and shaped like the head of a parrot complete with beak.

From my home, it's just 13° above the horizon at culmination, so I thought I didn't have high hopes of seeing even in a 15-inch reflector. Oh, but I was wrong.

After a quick star hop from 3rd magnitude γ Sagittarii at the tip of the Teapot's spout (just 2.2° to the north-northeast), I immediately spotted a dark "puddle" in a rich star field. With a little averted vision, the outline of the head jumped right out, but the best parts were the curved beak — which has a delightful hooked shape — and the eye. Dark, light-absorbing dust thins around the eye, creating an eye socket of faint background stars, at the center of which gleams the eye itself, a 12th magnitude star. The effect was uncanny.

Swan Nebula (M17)

The Swan is well known to amateurs as one of the brightest and most beautiful nebulae of the season. Located 9.3° almost due north of λ Sagittarii, the star at the top of the Teapot, and 20′ southeast of a 5th magnitude star, it's just visible with the naked eye. Through 10x50 binoculars from rural skies, I can see a remarkable amount of detail. The torpedo-like shape of the swan's body is obvious with a faint curtain of additional nebulosity laced with faint stars fanning to the northeast.

Hunter Wilson

Whenever I view the Swan in a telescope, I use a light-pollution-reducing UHC or OIII filter, even in the country. It removes natural airglow and reveals a blotchy body and graceful, curving neck of the bird in spectacular contrast against a velvet sky.

Strands of dark nebulae split the body into individual mottles that strongly resemble the texture of the Orion Nebula. East of the swan, you'll see a rounded "wake" of faint nebulosity left by the swan as it majestically glides across the dark night. A dab of nebulosity misting a small star appears just over the head — a cygnet wading next to mama? Dabble all you like here, there's much to see.

Eagle Nebula (M16)

Bob King

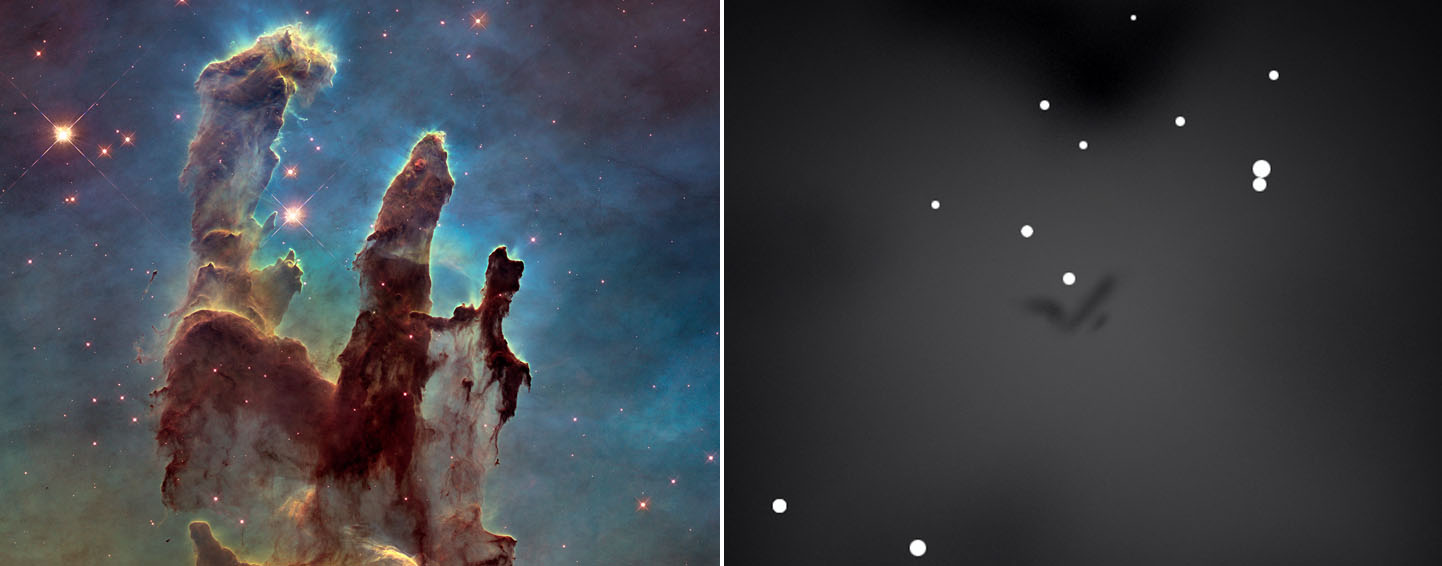

Here's another bright, easy Messier object just over the border from Sagittarius in Serpens. Since it's only 2.3° NNW of the Swan, start there first and then give your scope a push north until you run into the Eagle. M16 is a cluster of massive, young stars swaddled in bright nebulosity, both aspects visible in my 10x50s. In many clusters, stars are thickest in the center, but here the center is veiled in milky nebulosity with two bright bunches of stars clustered along the north and south sides.

A prominent dark nebula takes a triangular bite out of the M16's north side, but you've got to dig for the real prize, three dark, bony fingers nicknamed the "Pillars of Creation" made famous in a 1995 Hubble Space Telescope photo. The very same pillars also form the silhouette of an eagle, M16's original claim to fame.

ESO

While the fingers stand out crisply in photos, their tantalizing form will require your best efforts and the right equipment. I use moderately high magnification (around 200x to 250x) coupled with an OIII or UHC filter and averted vision. 8-inch and larger scopes will show at least part of the feature.

NASA / ESA (left) and Bob King

Start at low magnification to get a fix on the eagle's position — she sits squarely in her nest of nebulosity just south of the aforementioned dark triangle — then increase the power to 200x and look for a single dark projection. That's the middle pillar (eagle's head) and the easiest of the trio. In moments of good seeing, with averted vision in overdrive, I can also make out the short stub to the pillar's west as well as the hump of darkness below and east of the pillar. The hump forms the base of the tallest pillar and also the eagle's wing. Sadly, it's either less opaque or lost in bright foreground nebulosity; I've never seen it with certainty.

The pillars are columns of cold gas and dust inside of which new stars are forming. They'd better hurry. The young stars just to its south are heating up and evaporating the dust, suffusing the pillar tops in a bluish haze of glorious destruction.

Created with Stellarium

There's reason to believe that our own sun formed in a similar cloud. Radioactive elements likely released when a nearby massive star exploded as a supernova were incorporated into our growing solar system. Before it passed, the star had the power to ionize and strip away gas in a way similar to what we see happening in M16.

After you've worked your eyes for the prize, pull back. Grab the binoculars again and sweep over the 5° field of view encircling Swan, Eagle, the Small Sagittarius Star Cloud and several other notable star clusters. It's one of the finest pieces of real estate in the summer sky.

Wild Duck Cluster (M11)

NASA

"It somewhat resembles a flight of wild ducks," wrote the 19th century English naval officer, Admiral William Smyth when he looked at M11 in 1835. I'd say more like a fan than a V but close enough.

This is one incredibly dense open cluster with something like 3,000 "ducks" in flight about 3° west of the stars π and λ Aquilae that outline the tail of Aquila the Eagle. No matter what size telescope you use, the cluster captivates. The assembly fans out to the west of a bright, 8th magnitude star near the center of, but not part of, the cluster.

What's always struck me about M11 are its square corners that give it the appearance of a box filled with glittering jewels. Located in Scutum some 5,500 light years away, M11's true diameter is 21 light years. When I drop in a medium magnification eyepiece, say 125x, I find it hard to imagine that all those stars would squeeze into nearly the same space as the distance from Earth to Vega (25 light years). If you waded to the center of the flock and looked around, your sky would sparkle with several hundred 1st magnitude stars along with a few dozen brighter than Sirius.

Pelican Nebula (IC 5070, IC 5067)

Hunter Wilson

Much like its real-life cousins that congregate in shallow lagoons and protected areas along the coast, you'll find this nebular namesake off the eastern coast of a fuzzy Florida in the North American Nebula in Cygnus. The large, dark molecular cloud, LDN935, not only separates the Pelican Nebula from the North American, it sculpts the bright, diffuse emission region into a picturesque profile of a pelican head.

At 60′x50′ across, use your lowest magnification and a nebular filter for the best view. The 1° field of view in my 15-inch reflector barely contains the bird. Better an 8-inch richest field scope with a giant 2-inch eyepiece — the ultimate astro-birder fantasy!

Patchy nebulosity, both bright and dark, covers the entire 3°x3° region that encompasses both the Pelican and its larger continental cousin, the North American Nebula. Bright stars and three star clusters add spangles. Binoculars will show the North American Nebula, but I have trouble with the Pelican. Maybe next time I'll try slipping an OIII filter over one eyepiece for a filtered view.

Bob King

Like other emission nebulae, stars are coalescing inside denser folds of the Pelican. And when it's their turn to shine, they'll set other gas clouds aglow, slowly contorting the pelican's shape into something we can't even imagine.

I hope you find some time for birdwatching before the Moon returns around July 28th. Take in the spirit of the creatures, grow some wings, and imagine yourself soaring along the Milky Way.

2

2

Comments

Bob

July 22, 2017 at 1:05 pm

Most interesting article. The Pelican Nebula always reminds me of a Heckle & Jeckle cartoon. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heckle_and_Jeckle

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

July 23, 2017 at 2:13 pm

Hi Bob,

I totally see the resemblance. Thanks for that ancient cartoon reference!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.