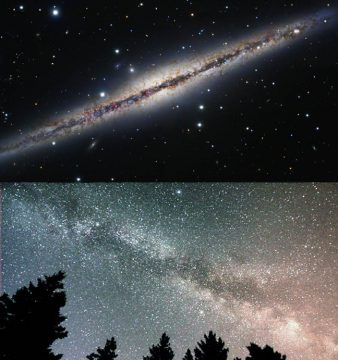

Stare up at the Milky Way band on a dark night and you'll see missing pieces from clouds of foreground dust that absorb the light of distant stars. There are other mottled "milky ways" just like ours, millions of light-years away. Care to join me for a look?

Robert Sälg

Dust makes lots of things possible. Without it, atmospheric water vapor would lack the nuclei needed for condensation and the formation of clouds and raindrops. Dust set aglow by sunlight animates the long, sweeping tails of comets. At the largest scale it riddles the spaces between the stars like lumps of brown sugar in oatmeal. Inside those lumps, cold and darkness is transformed back into heat and light as dust and gas gives birth to stars under the press of gravity.

Stay up really late on a spring night and you'll see the glowing clouds of starlight that announce the return of the summer Milky Way. On a dark night, you can easily see the band's uneven texture that includes vacuities like the dark "funnel cloud" arc north of Deneb and the Great Rift widening across Aquila. All these apparently starless areas are created by light-years-deep interstellar dust — ashes of star-death — that gathers in the plane of the galaxy and absorbs the light of more distant suns.

One of the great joys of observing is free space travel. Seeing sights familiar from our life on Earth played out in galaxies millions of light years away. That's one of the reasons we find galaxies striped with dust lanes so fascinating to look at — they're analogs of our own Milky Way. In exactly the same way dust in the galactic plane mottles the band of the Milky Way, exostellar grime subtracts starlight from external galaxies.

Top: Subaru NAOJ / NASA / ESA / West Mt. Observatory / Robert Gendler. Bottom: Bob King

Dust shows up best in silhouette if you're looking straight across the Milky Way, gazing through the plane of the galaxy. It stacks up in heaps! Were Earth far above the galactic plane, stardust would look much less impressive. Instead, we'd marvel at the spiral arms.

Similarly, galaxies we see edge-on are best for dust-lane gazing. Debris piles up along our line of sight and forms a dark band or stripe(s) across the its bright innards. If the galaxy is tilted slightly, we might still see dust belts streaking the outer disk provided the galaxy is a bright one like Andromeda, which is inclined 12.5°.

More distant galaxies reveal their dusky lanes indirectly as a sharp cutoff of light above or below the nuclear region. Tilts greater than about 20° make visual dust lane observations challenging.

Most galaxies are faint, and dust lanes are even fainter, so the larger the telescope, the better chance of spotting these sooty sleeks. NGC 891, AKA the Silver Sliver, is one of the finest with a tilt of just 1.5°. Sadly, it's slipping into the solar glare as I write this. But don't hang your head. There's more where that came from. Check these out!

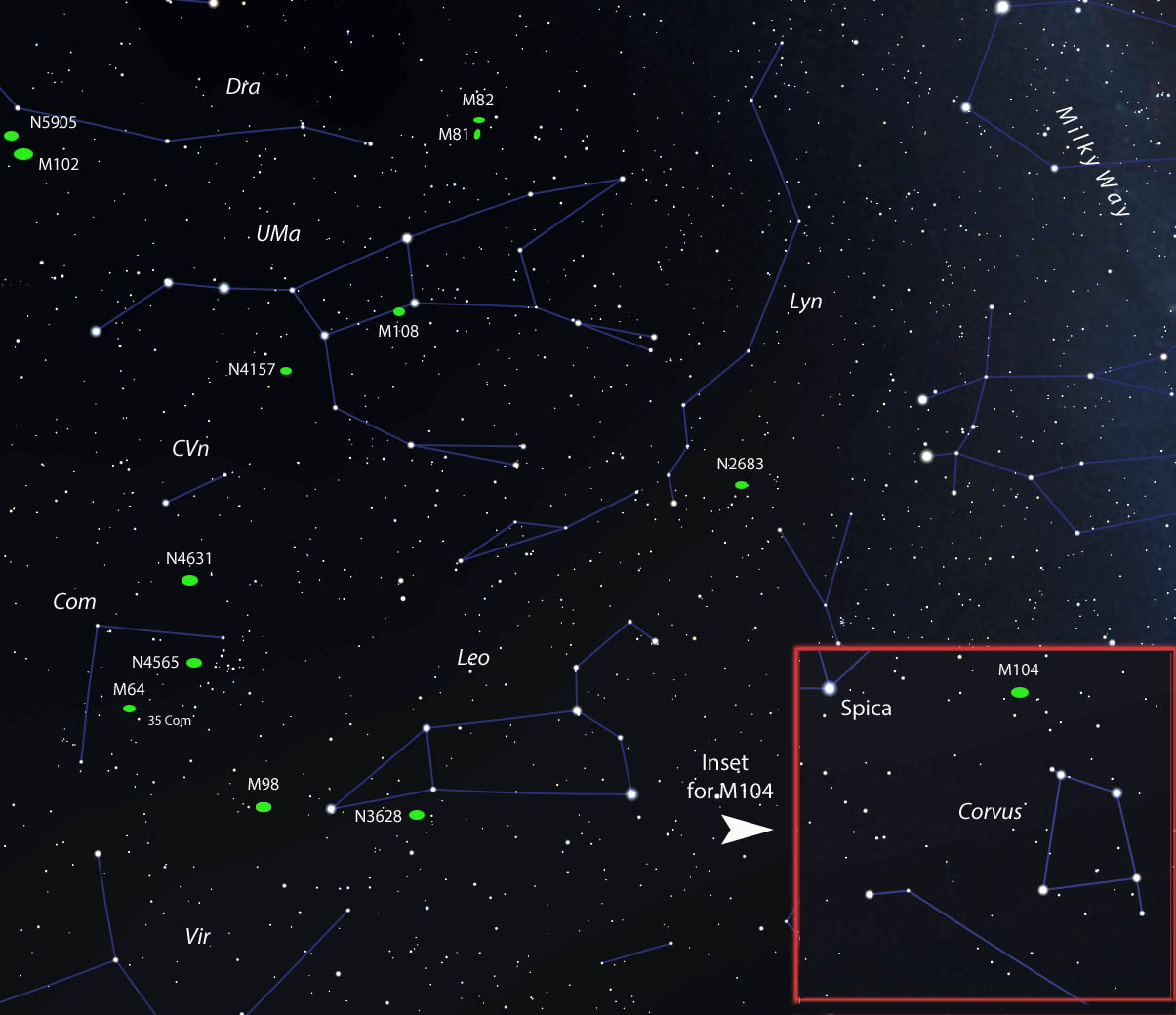

Jim Misti

- M64 (Black Eye Galaxy) in Coma Berenices: One of my very favorites and a great example of how using higher magnification (north of 150×) makes dust lanes stand out best. Located 1° northeast of 5th-magnitude 35 Comae Berenices, the 9th-magnitude galaxy is dimly visible in my finderscope. I can see a dab of darkness just north of the nucleus at 64×, but my happiest view comes at 286×, when a smile-shaped arc of dark dust partially encircles the pearly nucleus. Don't think you need a large instrument to see this one; it's apparent even in a 6-inch telescope. Use averted vision to boost the view.

Bob King

- M104 (Sombrero Galaxy) in Virgo: If you're wondering what heaven looks like, this is it. At least to my eyes. There's nothing like this galaxy — all soft, angelic light with a bright, fuzzy center and a dark, ethereal arc that divides the brighter southern half from the fainter north. The dust lane floats in the foreground, soaking up light from the faintly luminous northern region of the galaxy. An 8-inch or larger scope gives the best view. M104 is tipped 7° to our line of sight, the reason its two halves appear unequal.

DSS2

- NGC 4565 (Silver Needle Galaxy) in Coma Berenices: First recorded by William Herschel in 1785, this remarkably flat spiral galaxy is 15′ long × 1.5′ wide. Only 4° from edge-on, it resembles a pancake with a dollop of butter in the center, the butter representing the central bulge. I like to plunk in a high-magnification, wide-field eyepiece and see the galaxy splayed across the entire field of view. An 8-inch and larger telescope reveals a narrow lane of dust bisecting the bulge and continuing some distance into the flat disk. In my 15-inch at 286× with averted vision I can trace the lane across two-thirds of the galaxy's length. Located about 40 million light-years from Earth, NGC 4565 is about 100,000 light-years across, the same size as the Milky Way, and one of the magnificent sights in the spring sky.

DSS2

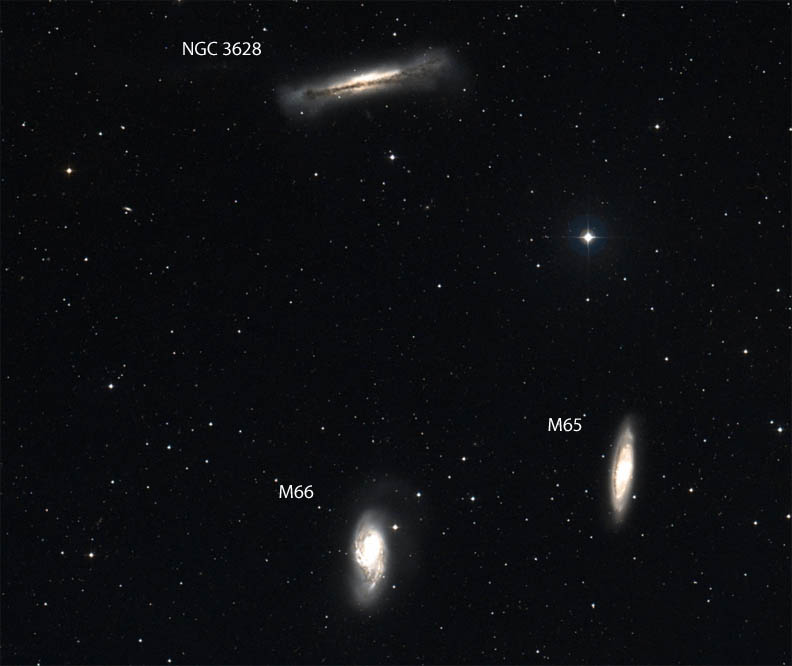

- NGC 3628 (Hamburger Galaxy) in Leo: Anybody hungry? I'll admit it does resemble America's favorite meal, but the meat's a little off center in the bun. In the 15-inch at 142× I can see the broad lane clearly enough with averted vision to tell that it cuts a little south of the galaxy's extended nuclear region.

Scott MacNeill, Frosty Drew Observatory

- M82 (Cigar Galaxy) in Ursa Major: In the previous four galaxies, dust in the galactic plane settles into a well-organized bar or arc. In M82, dust instead forms an blotchy network across the galaxy like seams of coal through lighter rock. The most obvious patch cuts right across the center of the galaxy and is visible in scopes as small as 6 inches. The larger your instrument the more dark dust blots you'll see.

Frank Colosimo

- NGC 4631 (Whale Galaxy) in Canes Venatici: Similar to M82, NGC 4631 shows lots of texture in 6-inch and larger telescopes with knots of star formation and several patchy dust clouds within the brighter nuclear region.

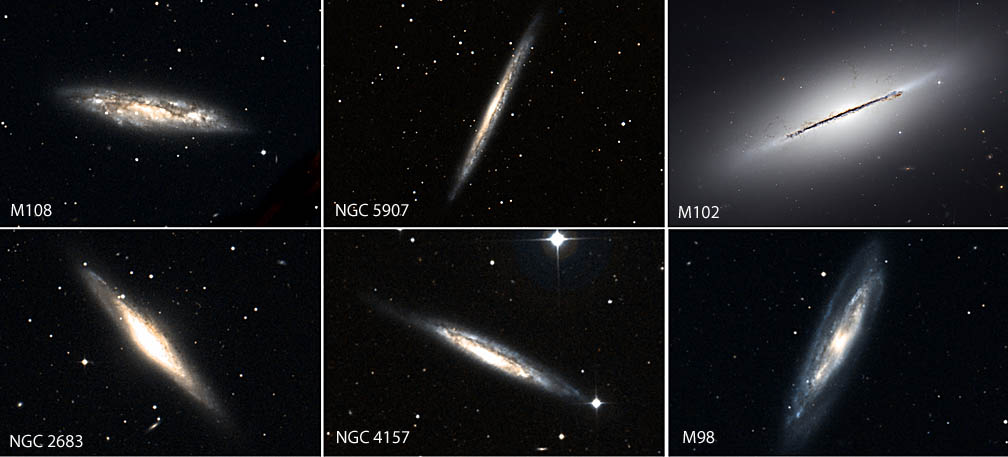

- M108 (Surfboard Galaxy) in Ursa Major: Here's another galaxy mottled with dust, particularly nearly the superimposed 12.5-magnitude star just west of the nucleus. Look for dark patches within the galaxy's northern perimeter. M108 shows lots of texture and a chunky, elongated shape. It's also easy to find just 1.5° southeast of Merak in the Bowl of the Big Dipper.

- NGC 5907 (Splinter Galaxy) in Draco: A wonderful splintery galaxy! Although a tad on the faint side at magnitude 11, you can't miss the striking, highly elongated disk measuring 12.7′ × 1.4′. I found the dust lane along the galaxy's western side tricky to see. With averted vision and 286× I finally discerned the star-snuffing dust as a steep drop-off in the galaxy's light along its western side. NGC 5907 is about 50 million light-years away.

DSS2 / SDSS / NASA / ESA / Hubble

- M102 (NGC 5866, the Spindle Galaxy) in Draco: A bright, compact, lens-shaped lenticular galaxy in the same low power field of view with NGC 5907. The two galaxies are the same distance from Earth and belong to the NGC 5866 Group. Photographs reveal a skinny but striking dust lane bisecting the galaxy's nuclear region. Based on the pictures you'd expect it to be a breeze to see. Nope. I tried for 20 minutes with the 15-inch and the best I could do was a weak, tentative " pencil line" crossing the galaxy with a magnification of 357× and averted vision.

- NGC 2683 (UFO Galaxy) in Lynx: As with NGC 5907, I couldn't make out the dust lanes in silhouette but rather as a steep cutoff in light along the spiral galaxy's south side. This is a bright, easy spiral galaxy of magnitude 10.6.

- NGC 4157 in Canes Venatici: Despite what appeared to be an obvious dark lane lining the north side of this galaxy, I had no luck seeing it. I don't doubt that its rather dim magnitude of 11.4 was a factor. Perhaps you'll succeed where I failed.

Stellarium

- M98 in Coma Berenices: Another miss for me. I was unable to convince myself of seeing the dust patches and lanes in this 11th-magnitude spiral galaxy.

By the time you're done surveying these charcoal wisps, you might notice a certain crustiness in the corners of your eyes. Yes, there's dust in that, too. No escaping it.

For more edge-on and dust-lane galaxies, download a free copy of Alvin Huey's Flat Galaxy Catalog.

2

2

Comments

Chuck Hards

April 12, 2018 at 11:51 am

Terrific article, Bob!

Just a minor nit, but aren't stars formed from gas predominantly, and (some) planets from dust?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 12, 2018 at 12:35 pm

Hey Chuck - thanks! Yes, that's true. I concentrated on the dust, the part we can see and also an essential element in star formation (the sun has all 92 natural elements, for instance) but yes, stars are formed predominately of gas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.