Some daily events in the changing sky for January 16 – 24.

Friday, January 16

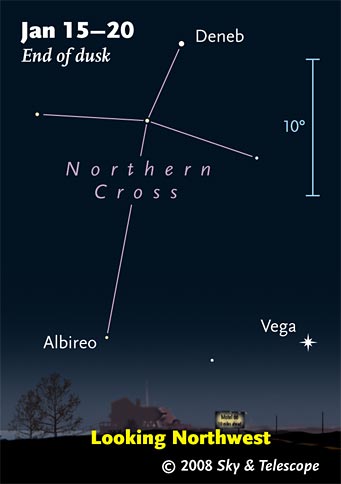

Whenever Vega is preparing to set, the Northern Cross is turning to stand upright on the northwest horizon (as seen from mid-northern latitudes.)

This scene, like the others, is drawn for our "standard latitude," 40° north. If you're farther north than that, Vega will be higher (maybe even circumpolar!). If you're farther south, Vega sets earlier in the evening and earlier in the season.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Meanwhile, bright Vega is getting lower and lower in the northwest in the cold winter twilight, as shown at right. Brrrr. "Summer Star" indeed!

Saturday, January 17

Sunday, January 18

Monday, January 19

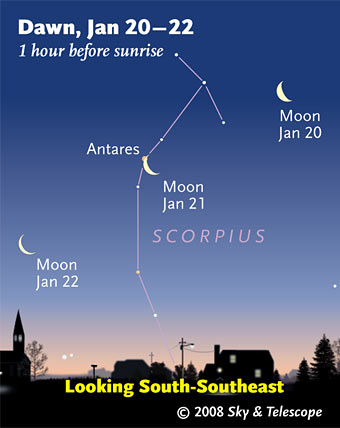

Early risers can watch the waning crescent Moon passing Antares before dawn. (These scenes are drawn for the middle of North America. European observers: move each Moon symbol a quarter of the way toward the one for the previous date. In the Far East, move it halfway. For clarity the Moon is shown three times actual size.)

Sky & Telescope diagram

Tuesday, January 20

Wednesday, January 21

Thursday, January 22

Friday, January 23

Saturday, January 24

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly foldout map in each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

The Pocket Sky Atlas plots 30,796 stars to magnitude 7.6 — which may sound like a lot, but that's less than one star in an entire telescopic field of view, on average. By comparison, Sky Atlas 2000.0 plots 81,000 stars to magnitude 8.5, typically one or two stars per telescopic field. Both atlases include many hundreds of deep-sky targets — galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae — among the stars.

Sky & Telescope

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of maps; the standards are Sky Atlas 2000.0 or the smaller Pocket Sky Atlas) and good deep-sky guidebooks (such as Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the even more detailed Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic Burnham's Celestial Handbook). Read how to use them effectively.

Can a computerized telescope take their place? As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind." Without these, they note, "the sky never becomes a friendly place."

More beginners' tips: "How to Start Right in Astronomy".

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury is lost in the glare of the Sun. It's at inferior conjunction on January 20th.

Venus (magnitude –4.5) is the dazzling "Evening Star" high in the southwest during and after twilight. It doesn't set until about 9 p.m.

In a telescope Venus is 26 arcseconds wide and just on the crescent side of dichotomy (half-lit). In reality, Venus is exactly 50% illuminated on the evening of Friday the 16th. But because the sunlight illumination is dimmer at the terminator, in a telescope the waning Venus usually looks exactly half-lit 5 or 10 days earlier than when it really is.

Telescopically, Venus is best seen in bright twilight or even broad daylight. (It's less glary when seen against a bright sky, and it's also higher.)

Mars is hidden deep in the glow of sunrise — and will remain so all winter and part of the spring.

Jupiter is lost in the sunset. It's at superior conjunction on January 24th.

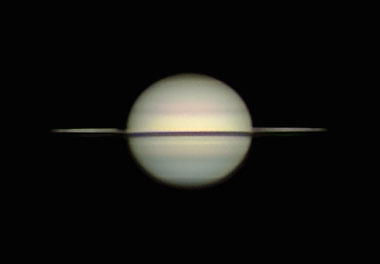

On Christmas night Richard Bosman in the Netherlands took this image of Saturn at its minimum ring tilt for this apparition, 0.8°. South is up. Bosman writes, "The northern part is still bluish. There were no storms or spots on display at this meridian. Remarkable is the beauty of the very narrow ring now at the minimum. The ring is not bright white but dull gray."

The Cassini Division is visible near the rings' ansae (ends). The shadow of the globe is cast on the ring's western (left) side just off the globe's edge. Even a small scope will show the very prominent black shadow that the rings are casting on the globe. Bosman used an 11-inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope and an ATK-2HS camera at 5:02 UT Dec. 26, 2008.

Saturn (magnitude +1.0, near the Leo-Virgo border) rises around 9 p.m. It's highest in the south around 3 or 4 a.m. Don't confuse Saturn with similarly-bright Regulus 22° (about two fist-widths at arm's length) to its upper right after they rise, and more directly to its right in the early-morning hours).

This week Saturn's rings are 1.0° to 1.1° from edge on. The rings will gradually open to 4° by late May, then will close to exactly edge-on early next September — when, unfortunately, Saturn will be out of sight in conjunction with the Sun. Saturn will again be poorly placed for our next ring-plane crossing 15 years hence. So now is the thinnest you can see Saturn's rings until 2038!

Uranus (magnitude 5.9, in Aquarius) is passing by Venus in the evening sky. Use binoculars and the illustration in the January Sky & Telescope, page 62.

Neptune is lost in the sunset.

Pluto is hidden in the glow of sunrise.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon or zenith — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) equals Universal Time (known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.