The waxing Moon pairs up with the two brightest planets on two days in succession. (These scenes are drawn for the middle of North America. European observers: move each Moon symbol a quarter of the way toward the one for the previous date. For clarity, the Moon is shown three times actual size.)

Sky & Telescope diagram

Friday, February 24

Saturday, February 25

Sunday, February 26

The gas and dust tails of Comet Garradd now point in almost opposite directions! Or so it appears. In fact, from Earth's perspective, the physically thin, flat dust tail appears nearly edge-on — as a broad fan spanning from left, through just below the comet's head as seen here, to the right nearly to the gas tail. We are looking almost straight down the tail. Paolo Candy in Italy took this image on February 25th. Stars are trails because Candy tracked multiple exposures on the comet's moving nucleus.

Monday, February 27

Tuesday, February 28

Wednesday, February 29

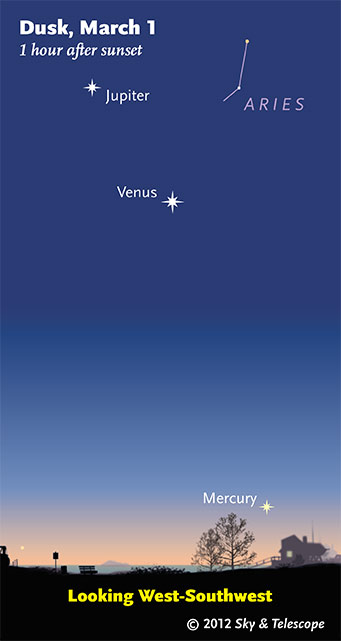

Venus and Jupiter continue to close on each other. They guide the way down to Mercury just above the sunset-afterglow horizon.

Alan MacRobert

Thursday, March 1

Then later tonight, the Moon's dark limb covers 3rd-magnitude Zeta Tauri for the Northeast and much of the Midwest. Some times: Toronto, 1:25 a.m. EST; Washington, DC, 1:36 a.m. EST; Chicago, 12:39 a.m. CST; Winnipeg, 12:16 a.m. CST. More times.

Friday, March 2

Saturday, March 3

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

Sky Atlas 2000.0 (the color Deluxe Edition is shown here) plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5. That includes most of the stars that you can see in a good finderscope, and typically one or two stars that will fall within a 50× telescope's field of view wherever you point. About 2,700 deep-sky objects to hunt are plotted among the stars.

Alan MacRobert

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The standards are the little Pocket Sky Atlas, which shows stars to magnitude 7.6; the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 8.5); and the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts effectively.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's new Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic if dated Burnham's Celestial Handbook.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? I don't think so — not for beginners, anyway, and especially not on mounts that are less than top-quality mechanically. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury (about magnitude –1.0) is emerging into its best evening apparition of 2012. As the afterglow of sunset fades in the west, look for Mercury far to the lower right of bright Venus.

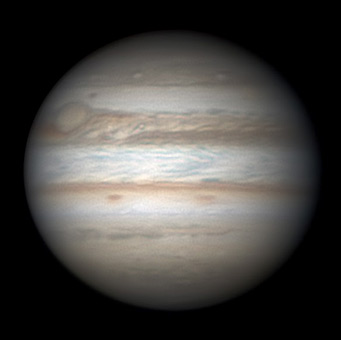

The Great Red Spot was about to rotate off Jupiter's visible disk when Christopher Go in the Philippines took this image on February 27th local time. South is up.

Venus and Jupiter (magnitudes –4.2 and –2.2) are the two bright “Evening Stars” shining in the southwest to west during and after dusk. Venus is the brighter, lower one. Watch Jupiter closing in on it by 1° every day! The gap between them narrows this week from 17° to 10°. These are the two brightest celestial objects after the Sun and Moon.

In a telescope, Venus is a brilliant white gibbous disk 18 arcseconds tall and 65% sunlit. Jupiter shows a much lower surface brightness, being farther from the Sun, but it's bigger: 36 arcseconds wide.

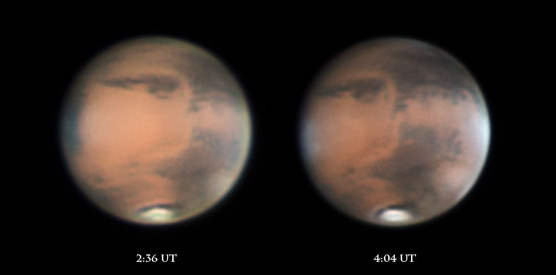

Mars (about magnitude –1.2, in western Leo) is nearing its March 3rd opposition. It rises bright fire-orange in the east during twilight and dominates the eastern sky after dark. The star to its left or lower left is Denebola, the tail of Leo. Mars shines highest in the south, in best telescopic view, around midnight or 1 a.m.

In a telescope Mars has grown to 13.7 or 13.8 arcseconds wide, basically identical to the 13.9″ it will display when it's nearest to Earth March 5th.

At the Winter Star Party in the Florida Keys, veteran planetary imager Don Parker and S&T's Sean Walker took these first-rate Mars images using a 14-inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain scope on the night of February 24–25. Mars was 13.7 arcseconds wide. Don't expect views this good visually!

South is up. Sinus Sabaeus and Sinus Meridiani are above center in the image at left. The North Polar Cap (NPC) has been shrinking in the Martian northern-hemisphere spring, exposing the dark collar around it. "Note the rift in the NPC," writes Walker, "which corresponds to the position of Rima Tenuis."

Don Parker / Sean Walker

.

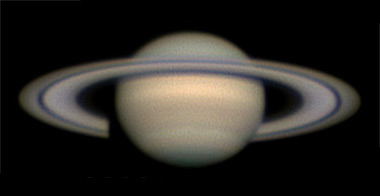

Saturn's rings are tipped a good 15° from our line of sight. South is up. Note the very pale light band in the north temperate region, the remnant of the dramatic, billowing white outbreak that attracted so much attention last year. Christopher Go took this image on January 21, 2012.

Saturn (magnitude +0.5, in Virgo) rises in the east around 10 p.m. and shines highest in the south around 3 or 4 a.m. Spica, a little fainter at magnitude +1.0 (and bluer), is 7° to Saturn's right or upper right. Saturn's rings are tilted a generous 15° from our line of sight, the most open the rings have appeared since 2007.

Uranus is disappearing into the sunset.

Neptune is hidden behind the glare of the Sun.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

Like This Week's Sky at a Glance? Watch our new weekly SkyWeek TV short. It's also playing on PBS!

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.