Comet PanSTARRS update. The incoming comet that we hoped would make a fine showing in March has been weakening. It may not even reach naked-eye visibility, what with its low altitude in evening twilight. See Comet PanSTARRS Punking Out?, and follow our continuing updates at SkyandTelescope.com/panstarrs.

Friday, February 1

Saturday, February 2

Wherever you are, Jupiter and Capella pass closest to your zenith exactly one hour apart. Jupiter goes first.

Sunday, February 3

Monday, February 4

Later, Jupiter's Great Red Spot rotates across the planet's centerline at 11:25 p.m. EST.

Tuesday, February 5

What you're seeing is sunlit interplanetary dust — comet and asteroid debris — orbiting the Sun near the plane of the solar system.

Mars appears less than 1° upper left of much brighter Mercury low in the west-southwest after sunset on February 7th.

Sky & Telescope diagram

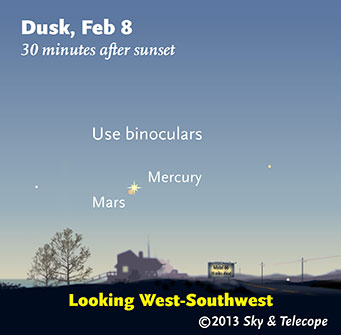

Mercury appears less than ½° upper right of much fainter Mars shortly after sunset on February 8th.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Wednesday, February 6

Thursday, February 7

Friday, February 8

Saturday, February 9

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

The Pocket Sky Atlas plots 30,796 stars to magnitude 7.6 — which may sound like a lot, but that's less than one star in an entire telescopic field of view, on average. By comparison, Sky Atlas 2000.0 plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5, typically one or two stars per telescopic field. Both atlases include many hundreds of deep-sky targets — galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae — to hunt among the stars.

Sky & Telescope

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The standards are the little Pocket Sky Atlas, which shows stars to magnitude 7.6; the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 8.5); and the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts with a telescope effectively.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the beloved if dated Burnham's Celestial Handbook.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and certainly not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (able to point with better than 0.2° repeatability). As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their invaluable Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

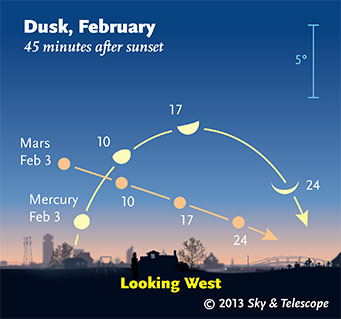

Mercury peaks in the early evening sky from February 11th to 21st, while much fainter Mars appears lower each evening. The two planets pass spectacularly close to each other on February 7th and 8th. Their disks are shown in their correct shapes and orientations, but their sizes are exaggerated hugely, roughly matching their appearance through a telescope at high magnification.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Mercury (magnitude –1.1) is emerging from the glow of sunset. On February 1st it's still very deep in bright twilight, but day by day it becomes higher and easier to see. Check for it each clear evening starting about 30 minutes after sunset, just above the west-southwest horizon. Bring binoculars.

There too is fainter Mars. Mars is above Mercury until February 7th and 8th, when they pass less than 1° apart. After that Mercury is higher — coming into an excellent apparition of its own. See Mercury in February 2013.

Venus (magnitude –3.9) is buried deep in the glow of sunrise.

Mars (magnitude +1.2) is sinking deeper into the sunset. Brighter Mercury becomes your marker for finding it this week.

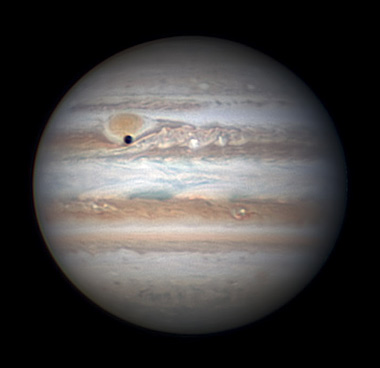

The shadow of Ganymede was passing the Great Red Spot when Christopher Go took this image of Jupiter at 10:59 UT February 6th. South is up. Note the white outbreaks in the South Equatorial Belt downstream from the Great Red Spot.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.5, in Taurus) dominates the high south in early evening, and the southwest later. To its left is orange Aldebaran; to its right are the Pleiades. The whole group sets around 2 or 3 a.m.

In a telescope, Jupiter is shrinking (from 43 to 42 arcseconds wide this week) as Earth pulls farther ahead of it in our faster orbit around the Sun.

Saturn (magnitude +0.5, in Libra) rises in the east-southeast around midnight or 1 a.m. local time. By the beginning of dawn it's at its highest in the south — more or less between Spica, far to its right, and Antares farther to its lower left. Saturn's rings are tilted 19° from edge on, the widest they've appeared in seven years.

This extraordinary amateur image of Saturn was captured by Darryl Pfitzner Milika in Australia on January 26th. He used a 14-inch Celestron Schmidt-Cassegrain scope and an ASI120MM planetary video camera for frame-stacking. Just visible is the hexagonal shape of the storm that surrounds Saturn's north pole. The hexagon shape was first discovered by the Cassini spacecraft in 2007. South is up.

Also visible in his image are four of Saturn's moons. From left: Dione, Enceladus, Mimas (!), and Tethys. Click for larger view.

Darryl Pfitzner Milika

.

Uranus (magnitude 5.9, in Pisces) is getting low in the west after dusk.

Neptune (magnitude 8.0) is lost in the sunset glow, in the background of Mercury and Mars.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

Like This Week's Sky at a Glance? Watch our SkyWeek TV short. It's also playing on PBS!

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.