Friday, February 5

• You can still see all five naked-eye planets at dawn, though Mercury is getting lower. On Saturday morning the 6th, the crescent Moon, Venus, and Mercury form a triangle low in the southeast, as shown here. See Bob King's article It's Not Over Till the Fast Planet Sinks.

Saturday, February 6

• Bright Capella high overhead, and equally bright Rigel in Orion’s foot, are at almost the same right ascension. This means they cross your sky’s north-south meridian at almost the same time (around 8 p.m. this week, depending on how far east or west you live in your time zone). So whenever Capella passes its very highest overhead, Rigel marks true south over your landscape. And vice versa.

Sunday, February 7

• In early evening this week the Pleiades pose very high in the southwest, with the Hyades and Aldebaran to their left. Nearly twice that far below the Pleiades glimmers one lone, modestly bright star: Menkar, or Alpha Ceti, in the head of dim Cetus the Whale. Can you see its orange tint?

Monday, February 8

• Look due east after dark, fairly low, for twinkly Regulus. Extending upper left from it is the Sickle of Leo, a backward question mark. Jupiter rises below it later in the evening.

"Leo announces spring," goes an old saying. Actually, Leo showing up in the evening announces the cold, messy back end of winter. Come spring, Leo will already be high.

• New Moon (exact at 9:39 a.m. EST).

Tuesday, February 9

• With the Moon new and Orion high, explore the rabbity telescopic sights of Lepus, the Hare under Orion's feet, using Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders article, chart and photos in the February Sky & Telescope, page 50. Get to know winter's only globular cluster. And what about that sextuple star that got named NGC 2017?

Wednesday, February 10

• By 9 or 9:30 the Big Dipper stands on its handle in the northeast. In the northwest Cassiopeia also stands on end, at about the same height.

Thursday, February 11

• Look west-southwest at nightfall for the thin crescent Moon. High above it, by some 30°, the two brightest stars of Aries point down to it. Above or upper left from there you'll find the Pleiades.

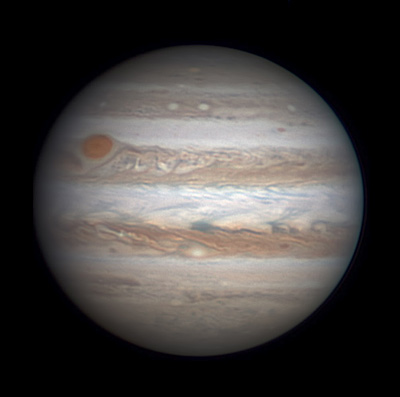

• It's a busy night around Jupiter. Europa's shadow crosses the planet's face from 9:02 to 11:51 p.m. EST, followed by Europa itself from 10:15 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. EST. And Io's shadow moves onto Jupiter starting at 12:51 a.m. EST. Subtract 3 hours from these to get Pacific Standard Time.

Friday, February 12

• The sky's biggest asterism (informal star pattern) is the Winter Hexagon. It fills the heavens toward the east and south these evenings. Start with brilliant Sirius at its bottom. Going clockwise from there, march through Procyon, Pollux and Castor, Beta Aurigae and Capella near the zenith, Aldebaran over and down to Capella's lower right, down to Rigel in Orion's foot, and back to Sirius.

Saturday, February 13

• Orion is now high in the south-southeast right after dark. Left of it is Gemini, headed up by Castor and Pollux at far left. The stick-figure Twins are still lying on their sides.

Well below their legs is bright Procyon in little Canis Minor, the doglet whose top is barely seen in profile (in a dark sky). He's currently vertical. Procyon marks his rump.

__________________________

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or new Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5, nearly three times as many. Next up, once you know your way around, is the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts with a telescope.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, or the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (meaning heavy and expensive). As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury (magnitude –0.1) is sinking a little lower in the southeast before dawn. But you can still spot it 4° or 5° lower left of brilliant Venus.

Venus (magnitude –3.9) is also gradually getting lower in the southeast during dawn.

Mars (magnitude +0.7, in the center of Libra), rises around 1 a.m. and glows yellow-orange in the south as dawn begins. In a telescope it's still a small 7 arcseconds in diameter. Notice its gibbous shape; Mars is at western quadrature this week (90° west of the Sun).

Mars will appear more than twice as large, 18.6 arcseconds in diameter, when closest to Earth in late May and early June.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.4, between Leo and Virgo) rises in the east around 8 p.m. and shines highest in the south around 2 a.m. By dawn it's getting low in the west-southwest.

Saturn (magnitude +0.5, in southern Ophiuchus) rises around 3 a.m. and is fairly well up in the south-southeast by the beginning of dawn. Spot Antares 7° to its lower right. Mars glows three times as far to Saturn's right or upper right. In a telescope, Saturn's rings are tilted a wide-open 26° from edgewise.

Uranus (magnitude +5.9, in Pisces) is still in the west right after dark. Finder chart.

Neptune (magnitude +8.0, in Aquarius) is getting lost in the sunset.

Planet Nine (probably fainter than magnitude 22, and probably not in the zodiac) seems reasonably likely to be out there, but it could be anywhere along a wide sheaf of orbits inclined roughly 30° to the ecliptic. And it's most likely to be near its aphelion, hundreds or even 1,000 a.u. away.

__________________________

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time (UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

__________________________

“This adventure is made possible by generations of searchers strictly adhering to a simple set of rules. Test ideas by experiments and observations. Build on those ideas that pass the test. Reject the ones that fail. Follow the evidence wherever it leads, and question everything. Accept these terms, and the cosmos is yours.”

— Neil deGrasse Tyson

2

2

Comments

Zubenelgenubi 61

February 7, 2016 at 11:08 am

It is impressive to see all of those planets, as I have on three mornings lately. I would say the best plan is to start an hour before sunrise to see Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, and Venus, and then hunt down Mercury. I was able to see Mercury with the naked eye on all three mornings, but this isn't a particularly good apparition and it certainly doesn't stand out. The best way to spot Mercury is to scan to the lower left of Venus (from mid-northern latitudes!) with binoculars. Once seen, it can be rather dimly glimpsed to the unaided eye. It may be easier or harder, depending upon the clarity of the sky. Probably around 45-50 minutes before sunrise is optimum for Mercury. It will be increasingly necessary to use binoculars to see it as February goes on. It might be possible to follow Mercury all the way in to March with binoculars, especially from the latitudes of the southern U.S.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

mary beth

February 7, 2016 at 5:19 pm

That's good advice, especially for those of us in Houston! Love this time of year for gazing!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.