Friday, March 17

• On the traditional divide between the winter and spring sky is the dim constellation Cancer. It lies between Gemini to its west and Leo to its east. Dim it may be, but Cancer holds something unique: the Beehive Star Cluster, M44, in its middle. The Beehive shows dimly to the naked eye if you have little or no light pollution. With binoculars, it's a snap even from fairly polluted areas. Look for it a little less than halfway from Pollux in Gemini to Regulus in Leo.

Saturday, March 18

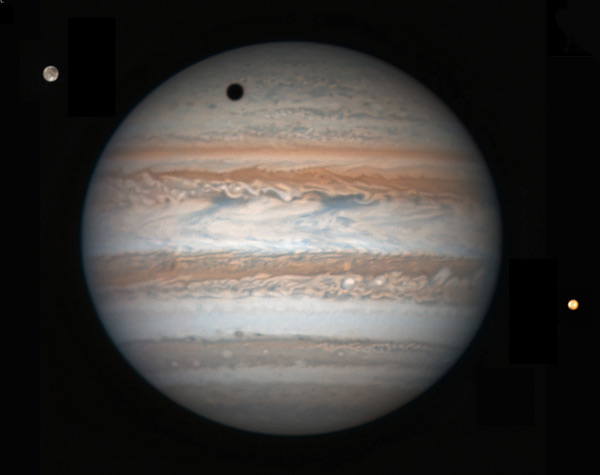

• Jupiter's moon Io, barely off Jupiter's western limb, disappears into eclipse by Jupiter's shadow around 10:24 p.m. EDT. A small telescope will show it slowly fade away.

Sunday, March 19

• Comet 41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak ("T-G-K") is becoming nicely visible in amateur telescopes high in the northern evening sky. Currently about magnitude 8, it may reach 6th magnitude at the end of March and stay about that bright through April. This comet has been known to flare in brightness. See our article Comet 41P/T-G-K Greens Up For St. Paddy’s Day.

NOTE: Use the new finder chart for the comet that's in that article. The charts for it in the May Sky & Telescope are significantly off due to an error in the ephemeris.

• For early risers Monday morning, the nearly last-quarter Moon is only a few degrees from Saturn. Look for them together early in the dawn, high in the south.

Monday, March 20

• Last-quarter Moon (exact at 11:58 a.m. EDT). The Moon rises tonight as late as 2 or 3 a.m. daylight saving time Tuesday morning. As Tuesday's dawn begins, look for Saturn well to the Moon's right, and the Sagittarius Teapot down to the Moon's lower right.

• The equinox comes at 6:29 a.m. EDT on the 20th, when the Sun crosses the equator heading north. Spring begins in the Northern Hemisphere, fall in the Southern Hemisphere. (And no, eggs don't balance any better than they usually do!)

Tuesday, March 21

• Arcturus, the "Spring Star," now rises above the east-northeast horizon just around the time the stars come out. How soon can you spot it? Brighter Jupiter comes up somewhat later (depending on your latitude), 30° to Arcturus's right.

Wednesday, March 22

• For skywatchers not far from 40° north latitude, now is the best day, or night, to try for a rare dual sighting of Venus — extremely low in the west-northwest shortly after sunset, and extremely low in the east shortly before sunrise. Binoculars will help. See the March Sky & Telescope, page 46.

Thursday, March 23

• Draw a line from Castor through Pollux high overhead, follow it farther out by a big 26° (about 2½ fist-widths at arm's length), and you're at the dim head of Hydra, the Sea Serpent. In a dark sky it's a subtle but distinctive star grouping, about the size of your thumb at arm's length. Binoculars show it easily through light pollution.

Friday, March 24

• This is the time of year when the dim Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) juts to the right from Polaris (the Little Dipper's handle-end) during late evening. The much brighter Big Dipper curls over high above it, "dumping water" into it.

Saturday, March 25

• Jupiter's moon Io disappears into eclipse by Jupiter's shadow, barely off Jupiter's western limb, around 12:18 a.m. EDT tonight (11:18 p.m. CDT). A small telescope is all you'll need.

• Venus reaches inferior conjunction, 8° north of the Sun.

_________________________

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations! They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, is the even larger Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts with a telescope.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, or the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (meaning heavy and expensive). And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

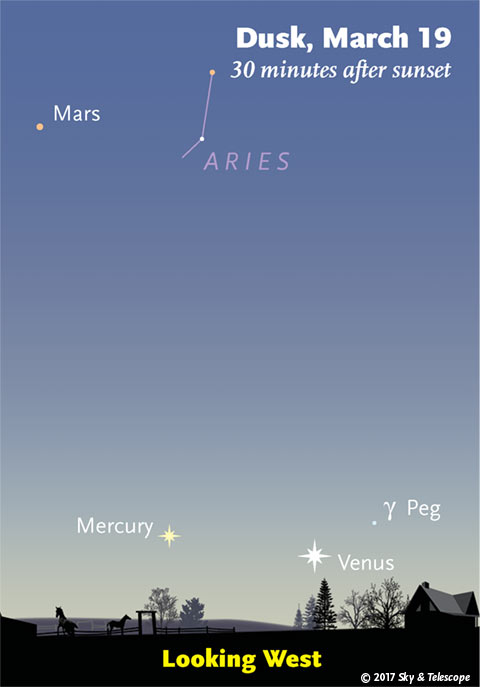

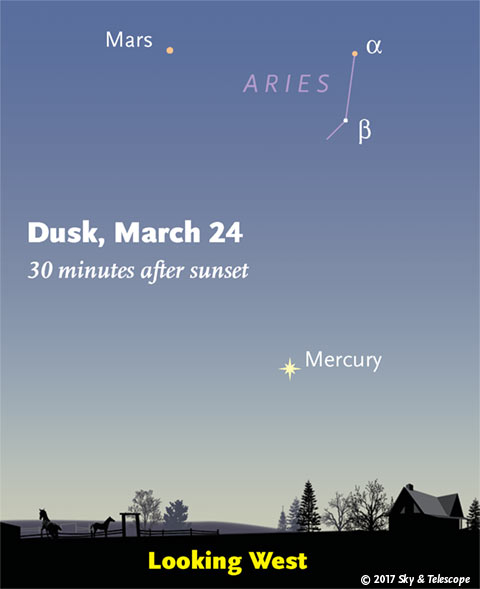

Mercury (magnitude –1.3) glimmers in evening twilight near brilliant Venus early this week. On March 17th look for Mercury 9° (almost a fist-width) to Venus's left or lower left. Every evening after that, Mercury gets a little higher while Venus drops lower toward its conjunction with the Sun.

Venus (about magnitude –4.2) is dropping fast low in the western evening twilight. It's swinging closer to our line of sight to the Sun, making it an ever thinner crescent in a telescope or high-quality binoculars. It's now a big 58 arcseconds from cusp to cusp, and from March 17th to 25th, its phase thins from just 3% to 1% sunlit!

Get your scope on Venus before sunset — while keeping the Sun behind a western horizon obstruction so you don't accidentally sweep across the Sun's blinding face. Can you detect any sign of cusp extensions around Venus's rim? More info is in the March Sky & Telescope, page 52, and See an Ultra-Thin Crescent.

Venus reaches inferior conjunction on March 25th, when it passes a full 8° north of the Sun (upper right of the Sun as seen around sunset from mid-northern latitudes). For Northern Hemisphere observers, this is the ideal apparition for following Venus way down in the west right after sunset — and picking it up very low in the east before sunrise. In fact, plan to look for it at both dusk and dawn on the same day, or across the same night! Your best bet for this rare dual sighting of Venus is on March 22nd if you're near 40° north latitude — as told in the March Sky & Telescope, page 46.

A tip for attempting to detect the crescent of Venus naked-eye when it's this large: sight through a tiny, smooth round hole in a piece of paper or cardboard held against your eye, to mask off aberrations in the outer part of your eye's pupil. Experiment with different size holes.

Mars (magnitude +1.4, in Aries) is the brightest "star" moderately low due west in late twilight. The orange stars Alpha Arietis and Alpha Ceti in the same general area are fainter. In a telescope, Mars is a hopeless little fuzzblob 4.4 arcseconds across.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.4, in Virgo) rises soon after nightfall and shines high in the southeast by 11 p.m. Spica dangles 4° or 5° lower right of it after they rise, directly below it around midnight, and lower left of it in early morning hours. By dawn they're low in the southwest.

In a telescope Jupiter is 44 arcseconds across its equator. It will remain this big through its April 7th opposition and nearly to April's end.

Uranus and Neptune are hidden in the glow of dusk and dawn, respectively.

__________________________

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time (UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 4 hours.

__________________________

"This adventure is made possible by generations of searchers strictly adhering to a simple set of rules. Test ideas by experiments and observations. Build on those ideas that pass the test. Reject the ones that fail. Follow the evidence wherever it leads, and question everything. Accept these terms, and the cosmos is yours."

— Neil deGrasse Tyson, 2014

"Objective reality exists. Facts are often determinable. Vaccines stop diseases. Carbon dioxide causes greenhouse warming. Science and reason are no political conspiracy; they are how we discover reality. Civilization's survival depends on our ability, and willingness, to do so."

— Alan MacRobert, your Sky at a Glance editor

"Facts are stubborn things."

— John Adams, 1770

Stand against falsehoods, denialism, and suppression of research. March For Science on April 22nd, in Washington DC and 410-plus other cities and towns, to “champion publicly funded and publicly communicated science as a pillar of human freedom and prosperity.”

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.