Oct. 31, 2006

Contacts:

Alan MacRobert, Senior Editor

855-638-5388 x151, [email protected]

Marcy McCreary, VP Mktg. & Business Dev.

855-638-5388 x143, [email protected]

| Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by publication-quality graphics; see details below. |

Usually you expect to see planets at night. But in broad daylight on Wednesday, November 8th, the planet Mercury will cross the face of the Sun. It will be visible in silhouette through a telescope with a safe solar filter placed securely over the front. Mercury will "transit" the Sun for about five hours, looking like a tiny round sunspot creeping westward across the enormous surface of our home star.

Transits of Mercury don't happen very often. The last was on May 7, 2003, and the next doesn't come until May 9, 2016.

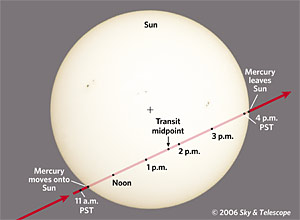

Well-prepared observers will see Mercury edge onto the Sun's face around 2:12 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (1:12 p.m. Central, 12:12 p.m. Mountain, 11:12 a.m. Pacific). Watchers in western North America can see the entire transit, which ends when Mercury slips off the Sun's edge at 4:10 p.m. Pacific time. Farther east, the Sun will set while the transit is still in progress.

How to Watch

Of course, you'll have to be Sun-safe! You can burn a permanent blind spot in your eye's retina by trying to observe the Sun without proper protection — and a telescope makes the danger more intense. You'll need a safe solar filter designed to go over the front of your telescope. Alternatively, you can project the Sun's image out of the eyepiece of a telescope or binoculars onto a white card held a foot or two away; turn the focus knob to get a sharp image of the Sun on the card. For details and illustrations see "How to Watch a Partial Solar Eclipse Safely" at SkyandTelescope.com/eclipse. SkyandTelescope.com is the website of Sky & Telescope and Night Sky magazines — both of which have more about the transit and how to observe it in their current issues.

What to Expect

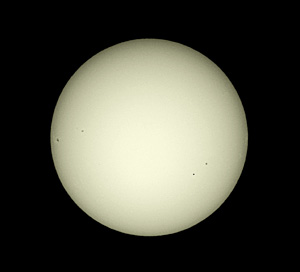

What will you see? Mercury is remarkably tiny compared to the Sun, appearing only 1/200 as wide during this transit. Even so, the little planet is big enough that in a safely filtered telescope, the total blackness of its silhouette can be distinguished from the dark gray of any sunspots that may be present. (It's possible, though, that the Sun will display no spots; the Sun is currently near the minimum of its 11-year sunspot cycle.)

The transit begins at first contact. This is when Mercury's leading edge first touches the Sun's southeastern edge. The time differs by a couple of minutes depending on where on Earth you're looking from. (For exact predictions at many locations, see NASA's Transit of Mercury website.) Second contact, when Mercury's trailing edge enters the Sun's disk, comes slightly less than two minutes later.

Deepest transit occurs around 4:41 p.m. EST, when Mercury is a little closer to the Sun's center than edge. The transit ends within a couple minutes of 4:08 p.m. Pacific Standard Time, 5:08 p.m. Mountain Standard Time. Farther east, as noted, the Sun has already set.

Why Is This Unusual?

Why are these transits so rare? Why don't we see one every time Mercury comes between the Sun and Earth? It's because the orbits of planets are slightly tipped with respect to one another. If Mercury and Earth revolved around the Sun in exactly the same plane, the innermost planet would indeed cross the Sun from our viewpoint every few months. But Mercury's orbit is tipped 7° relative to Earth's. So when Mercury passes between Earth and the Sun (during what astronomers call inferior conjunction), it usually passes a bit above or below the Sun from our viewpoint.

But twice each year, around May 9th and November 10th, the imaginary ellipse of Mercury's orbit is projected directly against the Sun as seen from our perspective. For a transit to occur, Mercury must slip between the Sun and Earth within a few days of those dates — and that happens only about 12 times per century.

As you watch this leisurely celestial ballet, revel in the rarity of the event and think of the astronomers in days of yore who might travel halfway around the world to observe and study and time a planet transit. Since the entire event lasts several hours, there'll be plenty of time to watch and share the experience with others. Throw a "transit party," and you might be surprised at how fast those hours fly by.

Sky & Telescope is pleased to make the following publication-quality graphics available to our colleagues in the news media. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted in the captions) are included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.com.

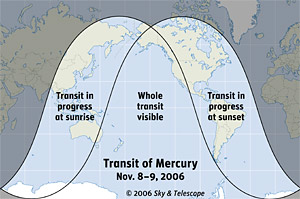

Some or all of the 5-hour transit will be visible from the Americas before sunset on November 8th, and after sunrise on the 9th from New Zealand, Australia, and the Far East. Click on the image to download a publication-quality version (120-kilobyte JPEG); it'll open in a new browser window. Sky & Telescope illustration by Casey Reed |

The farther west you live in North America, the better you're positioned to see most or all of the transit. Click on the image to download a publication-quality version (121-kilobyte JPEG); it'll open in a new browser window. Sky & Telescope illustration; source: Fred Espenak (NASA) |

It'll take nearly 5 hours for the innermost planet to glide across the Sun's face. This diagram shows its path, with celestial north up and east to the left. Where you see Mercury make its grand entrance, however, depends on your location. Click on the image to download a publication-quality version (68-kilobyte JPEG); it'll open in a new browser window. Sky & Telescope illustration by Casey Reed; source: Fred Espenak (NASA) |

Through a telescope with a specially designed solar filter placed securely over the front, the Sun may look something like this during the transit of Mercury on November 8, 2006. Can you tell which speck is Mercury and which are sunspots? The planet appears as a perfectly round, totally black disk, whereas a sunspot generally has a dark gray umbra (interior) skirted by a lighter gray penumbra (exterior). See the close-up view below to compare Mercury with a sunspot. Click on the image to download a publication-quality version (629-kilobyte JPEG); it'll open in a new browser window. Sky & Telescope photo-illustration by Richard Tresch Fienberg |

Through a telescope with a specially designed solar filter placed securely over the front, it should be relatively easy to distinguish the silhouette of Mercury from any other spots on the the Sun's face during the planet's transit on November 8, 2006. Mercury appears as a perfectly round, totally black disk, whereas a sunspot generally has a dark gray umbra (interior) skirted by a lighter gray penumbra (exterior). Sky & Telescope photo-illustration by Richard Tresch Fienberg |

About Sky Publishing

Sky Publishing, a New Track Media company, was founded in 1941 by Charles A. Federer Jr. and Helen Spence Federer, the original editors of Sky & Telescope magazine. In addition to Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.com, the company publishes Night Sky magazine (a bimonthly for beginners), two annuals (Beautiful Universe and SkyWatch), as well as books, star atlases, posters, prints, globes, and other fine astronomy products.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.