Contacts:

Alan M. MacRobert, Senior Editor

855-638-5388 x2151, [email protected]

J. Kelly Beatty, Senior Contributing Editor

617-416-9991, [email protected]

| Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by publication-quality illustrations; see details below. |

If it’s clear late on Saturday and Sunday nights (the nights of December 13th and 14th), keep a lookout high overhead for the “shooting stars” of the Geminid meteor shower. “The Geminids are usually one of the two best meteor showers of the year,” says Alan MacRobert, senior editor at Sky & Telescope magazine. “They are sometimes more impressive than the better-known Perseids of August.”

Under a clear, dark sky, you might see a shooting star every minute from 10 p.m. local time until dawn on the peak nights. If you live under the artificial skyglow of light pollution the numbers will be reduced, but the brightest meteors will still shine through. There will be some interference as well from a last-quarter Moon, which rises close to midnight.

Lower counts of Geminid meteors should be visible earlier on those evenings, and for a few nights before and after December 13th and 14th.

To watch for meteors, you need no equipment other than your eyes. Find a dark spot with an open view of the sky and no glaring lights nearby. Bundle up as warmly as you can in many layers. “Go out late in the evening, lie back in a reclining lawn chair, and gaze up into the stars,” says MacRobert. “Relax, be patient, and let your eyes adapt to the darkness."

Geminids can appear anywhere in the sky, so the best direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest, probably straight up. Small particles create tiny, quick streaks. Occasional brighter ones might sail across the heavens for several seconds and may leave a brief train of glowing smoke.

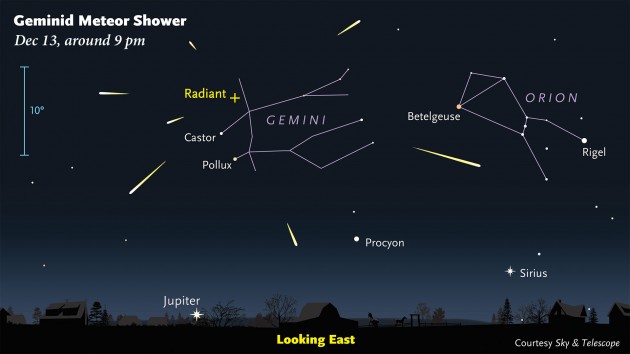

If you trace each meteor’s direction of flight backward far enough across the sky, you’ll find that this imaginary line crosses a spot in the constellation Gemini near the stars Castor and Pollux. Gemini is low in the eastern sky during late evening and climbs to high overhead in the hours after midnight (for skywatchers at north temperate latitudes). The special spot is called the shower’s radiant. It’s the perspective point from which all the Geminids would appear to come if you could see them approaching from far away, rather than just in the last second or so of their lives as they dive into Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Learn more about meteors and meteor watching.

The Source of the Geminid Meteors

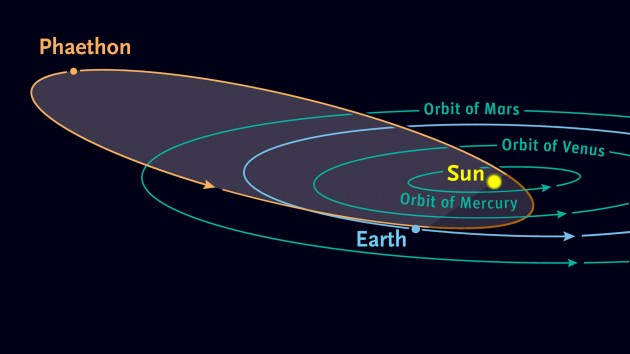

The Geminid meteors are created by tiny bits of rocky debris (the size of sand grains to peas) shed from a small asteroid named 3200 Phaethon, which was discovered in 1983. Before then no one knew the source of the Geminid shower. Phaethon is small, only about 3 miles across, and it loops around the Sun every 1.4 years in an orbit that approaches the Sun closer than any other known asteroid.

Over the centuries bits of Phaethon have spread all along the asteroid’s orbit to form a sparse, moving “river of rubble” that Earth passes through in mid-December each year. The particles are traveling 22 miles per second (79,000 mph) with respect to Earth at the place in space where we encounter them. So when one of them dives into Earth’s upper atmosphere, about 50 to 80 miles up, air friction vaporizes it in a quick, white-hot streak.

More about Light Pollution

Light pollution in the sky doesn’t interfere just with meteor watching. It’s the bane of everyone from backyard nature lovers to professional deep-space researchers. But most light pollution is unnecessary. It results from wasted light beamed uselessly sideways or upward from all of the poorly designed and improperly aimed outdoor lighting for many miles around.

This waste can be prevented by installing modern, fully shielded fixtures, and by aiming fixtures more downward toward the ground where the light is wanted. These simple steps not only reduce light pollution in the sky but allow great savings of electricity. "Be aware that some LED fixtures emit harsh, blue-hued light that makes it especially difficult to see the stars," notes S&T senior contributing editor Kelly Beatty. He recommends that you install LEDs with a "color temperature" (marked on the packaging) that's no greater than 3000K.

Sky & Telescope is making a publication-quality illustration available to our colleagues in the news media. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credit (as noted in the caption) is included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.com.

Sky & Telescope / Gregg Dindermann

Sky & Telescope / Alan Dyer

Sky & Telescope diagram

0

0