If skies are clear this weekend, we’ll see the full Moon. And not just any old full Moon, but the Blue Moon — the “true” Blue Moon.

Contacts:

Diana Hannikainen, Observing Editor, Sky & Telescope

+1 617-500-6793 x22100, [email protected]

Rick Fienberg, Press Officer, American Astronomical Society

+1 202-328-2010 x116, [email protected]

Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by high-quality graphics; see the end of this release for the images and links to download.

The full Moon of Sunday, August 22nd, will be a “Blue Moon” according to the original — but not the most popular — definition of the phrase.

In modern usage, “Blue Moon” has come to refer to the second full Moon in a month (the last of these occurred on October 31, 2020) — but that hasn’t always been the case. This colorful term is actually a calendrical goof that worked its way into the pages of Sky & Telescope in March 1946 and spread around the world from there.

Editors and contributors to Sky & Telescope have traced the traditional astronomical definition to the Maine Farmers’ Almanac in the late 1930s. he Almanac consistently used the term to refer to the third full Moon in a season containing four (rather than the usual three). “Introducing the ‘Blue’ Moon meant that the traditional full Moon names, such as the Wolf Moon and Harvest Moon, stayed in synch with their season,” says Diana Hannikainen (pronounced HUHN-ih-KY-nen), Sky & Telescope’s Observing Editor.

But in 1946, amateur astronomer and frequent contributor to Sky & Telescope James Hugh Pruett (1886–1955) incorrectly interpreted the Almanac’s description, and the second-full-Moon-in-a-month usage was born.

Sky & Telescope admitted to its “Blue Moon blooper” in the March 1999 issue (see “What Is a Blue Moon in Astronomy?”). Texas astronomer-historian Donald W. Olson, along with research librarian Margaret Vaverek at Texas State University, worked with the magazine’s editors at the time to figure out the origin of the mistake, and how the two-full-Moons-in-a-month meaning spread into the English language.

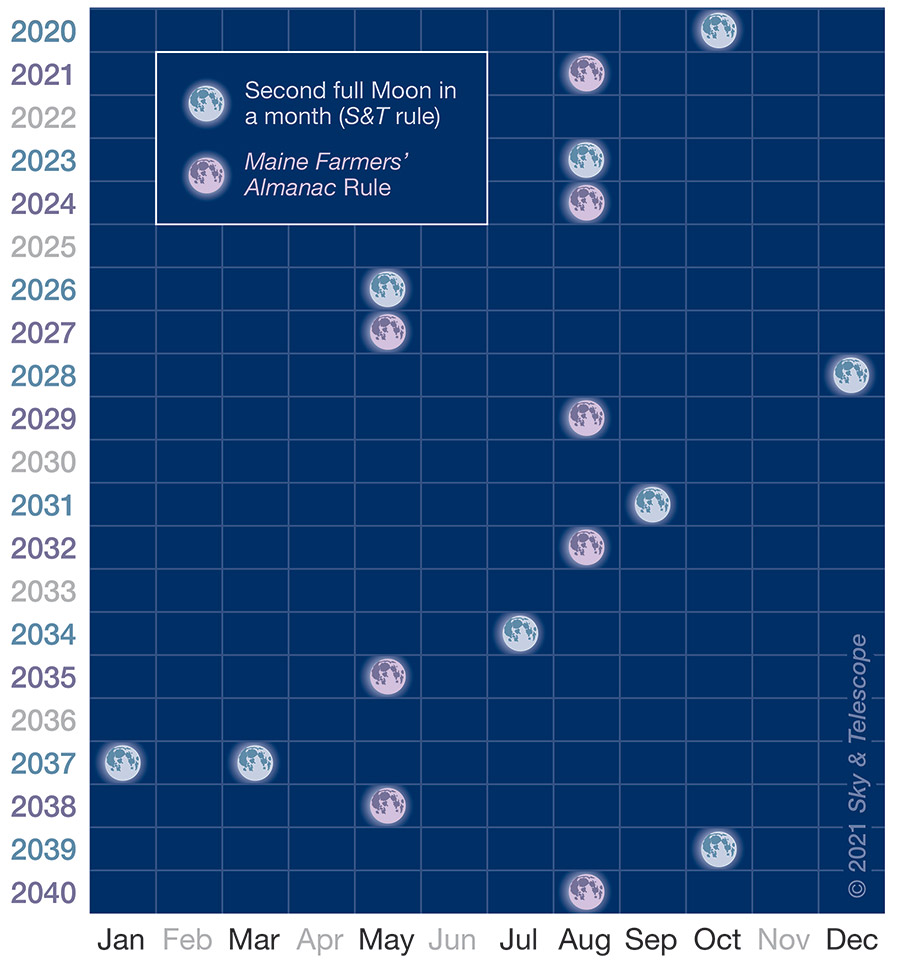

By either definition, Blue Moons are still relatively rare. They happen about once every 2.7 years on average. We get a “true” Blue Moon when the cycle of lunar phases causes the full Moon to occur within a few days after an equinox or solstice. The last such occurrence was in February 2019, and the next after this month’s will be in August 2024. We get a “Sky & Telescope” Blue Moon after a full Moon occurs on the first or second night of a month having 30 or 31 days, respectively; there can never be this type of Blue Moon in February, because full Moons occur 29.5 days apart. The next second-full-Moon-in-a-month Blue Moon comes in August 2023.

The Moon will be exactly full (that is, directly opposite the Sun) this month at 8:01 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (12:01 Universal Time), after the Moon has set as seen from the U.S. East Coast. This means that observers in the Americas will see nearly full Moons on two successive nights — August 21–22 and August 22–23 — with the Moon appearing closest to full before dawn and again after dusk on the 22nd.

Historically, the term “Blue Moon” was more often not an astronomical term: In older songs it's used as a symbol of sadness or loneliness, while “once in a blue Moon” means a rare event. Only exceedingly rarely does the Moon actually turn blue in our sky — when volcanic eruptions or forest fires send lots of smoke and fine dust into the atmosphere.

Popular culture has also enthusiastically adopted the phrase “Blue Moon” and applied it to many different things. As you wait for the Blue Moon to rise on August 22nd, you could treat yourself to a Blue Moon cocktail: In a tall glass filled with ice, mix four parts of gin to one part of blue curaçao and add a twist of lemon. Enjoy!

Sky & Telescope is making the illustrations below available to editors and producers. Permission is granted for nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted) are included. Web publication must include a link to skyandtelescope.org.

Gary Seronik

Sky & Telescope

Maine State Library

For skywatching information and astronomy news, visit SkyandTelescope.org or pick up Sky & Telescope magazine, the essential guide to astronomy since 1941. Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.org are published by the American Astronomical Society, along with SkyWatch (an annual beginner's guide to the night sky) as well as books, star atlases, posters, prints, globes, apps, and other products for astronomy enthusiasts.

The American Astronomical Society (AAS), established in 1899, is a major international organization of professional astronomers, astronomy educators, and amateur astronomers. Its membership (approximately 8,000) also includes physicists, mathematicians, geologists, engineers, and others whose interests lie within the broad spectrum of subjects now comprising the astronomical sciences. The mission of the AAS is to enhance and share humanity’s scientific understanding of the universe as a diverse and inclusive astronomical community, which it achieves through publishing, meeting organization, science advocacy, education and outreach, and training and professional development.

0

0