Contacts:

Diana Hannikainen, Observing Editor

855-638-5388 x22100, [email protected]

Gary Seronik, Consulting Editor

[email protected]

Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by high-quality graphics; see the end of this release for the images and links to download.

The Perseid meteor shower, an annual celestial event beloved by millions of skywatchers around the world, is about to make its annual return to the night sky. It’s predicted to reach its peak late on the night of Tuesday, August 11th, and early on Wednesday, August 12th. Head out after sunset and catch as many meteors as you can before the Moon rises shortly after midnight (local time).

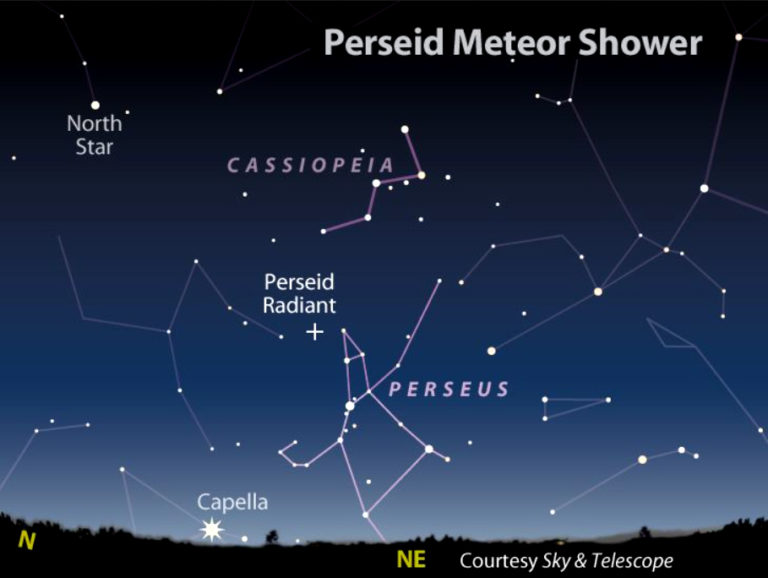

Begin watching for meteors soon after evening twilight ends. By then the shower's radiant, its perspective point of origin in the constellation Perseus, has risen above the northeastern horizon. The few Perseids that appear this early will be spectacularly long "earthgrazers" that skim along the top of the atmosphere. The higher the radiant, the more meteors you'll see — so when Perseus is higher in the northeast, more meteors will appear all over the sky.

The last-quarter Moon rises shortly after midnight and its light will wash out fainter meteors. But don’t despair: The Perseids are a long-lived event and you should see meteors — though fewer in number — for several nights before and after the night of the peak.

To enjoy the Perseids, you need no equipment but your eyes. Find a dark spot away from bright lights with a wide-open view all around if possible. Bring a reclining lawn chair or a ground cloth so you can lie back and watch the sky in comfort. Bundle up in blankets or a sleeping bag, both for mosquito shielding and for warmth; clear nights can grow surprisingly chilly. Next, relax, be patient, and let your eyes adapt to the darkness.

“These ‘shooting stars’ can appear anywhere and everywhere in the sky — you don’t have to look at the radiant to see them,” advises Diana Hannikainen (pronounced HUHN-ih-KY-nen), Sky & Telescope’s Observing Editor. “So the best direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest, usually straight up.” Faint Perseids appear as tiny, quick streaks. Occasional brighter ones might sail across the heavens for several seconds and leave a brief train of glowing smoke.

When you see a meteor, track its path backward. If you eventually come to the constellation Perseus — which climbs higher in the northeastern sky as the night progresses — then you’ve just witnessed a Perseid. Occasionally you might spot an interloper. The weaker Delta Aquariid and Kappa Cygnid showers are also active during Perseid season, and there are sometimes a few random, “sporadic” meteors. All of these track back to other parts of the sky. It’s a fun exercise to track these back to their radiants: If it’s not in Perseus, they’re not Perseids!

Any light pollution will cut down the numbers visible. But the brightest few meteors shine right through light pollution. In fact, a NASA analysis of all-sky images taken from 2008 to 2013 shows that the Perseids deliver more bright meteors (those that outshine any star) than any other annual meteor shower.

How and Why

Meteors are caused by tiny, sandgrain- to pea-size bits of dusty debris streaking into the top of Earth's atmosphere roughly 80 miles (130 km) up. Each Perseid particle zips in at 37 miles per second, creating a quick, white-hot streak of superheated air. The nuggets in Grape Nuts cereal are a close match to the estimated size, color, and texture of typical meteor-shower particles.

The Perseid bits were shed long ago by Comet Swift-Tuttle and are distributed all along the comet's 133-year-long orbit around the Sun. Earth passes through this tenuous “river of rubble” every year in mid-August. The comet is so named because it was independently discovered by Lewis Swift and Horace Parnell Tuttle in July 1862.

Graphics

Sky & Telescope is making the illustrations below available to editors and producers. Permission is granted for nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted) are included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.org.

Sky & Telescope illustration

Sky & Telescope illustration

Sky & Telescope

Sky & Telescope / Dennis di Cicco

For skywatching information and astronomy news, visit SkyandTelescope.org or pick up Sky & Telescope magazine, the essential guide to astronomy since 1941. Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.org are published by the American Astronomical Society, along with SkyWatch (an annual guide to the night sky) as well as books, star atlases, posters, prints, globes, apps, and other products for astronomy enthusiasts.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.