In which I attempt a contrarian argument against my own contrarian argument.

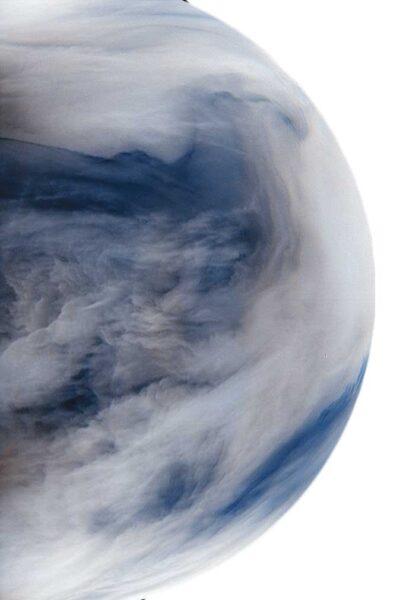

PLANET-C Project Team

For more than two decades I’ve been arguing that Venus — so often voted “least likely to succeed” by astrobiologists — might possibly harbor life. Not on the scorching surface but high up in the clouds, where temperatures are mild, nutrients and energy abound, and droplets consist of water that, while steeped in sulfuric acid, are less acidic than some environments where life is found.

This contrarian position has produced some eye-rolling at conferences, but nobody has come up with a good reason why it’s wrong. And now a funny thing has happened: An international workshop on Venusian cloud life held in Moscow in October 2019, along with several recent publications, appear to have moved the idea from the fringe to near-respectability.

Several results contribute to this shift. Observations from the Venus Express and Akatsuki missions have deepened some of the Venusian mysteries that cloud life might explain, such as unidentified airborne material that absorbs more than half the solar energy falling on Venus. Exoplanets in the “Venus zone” have renewed astronomers’ interest in the possible habitability of close-in planets. And new calculations point toward Venus having had water oceans for much of its lifetime.

So now let me tell you everything that’s wrong with the idea. Here’s why Venus is most likely a dead world:

Maybe life can’t live in clouds. Although microbes thrive in clouds on Earth, no known species lives its entire life cycle in this environment.

Maybe the chemistry of Venus’s clouds is just too harsh. While Earth does have acid-loving microbes, we don’t know the detailed composition of the Venusian cloud particles or whether they would be compatible with any form of life.

Maybe life couldn’t migrate to the clouds when the oceans disappeared, or maybe the clouds haven’t been continuously habitable. Evolution on Earth shows that life is extremely good at finding habitable niches and evolving when conditions change. But we don’t know if Venus has been continuously cloudy since the surface became uninhabitable, so a cloud niche may not have been stable over long time scales.

Maybe an ocean never had the right conditions. Some scientists think that for life to start you need oceans and continents. If early Venus had too much water and no land/water interface, life might not have arisen. Or a specific necessary environment, such as seafloor hot springs, might have been absent or chemically different enough to preclude life’s origin.

Maybe an ocean didn’t last long. Calculations showing that an ocean could have lasted for billions of years depend on several assumptions about early Venus. They require that the planet always rotated slowly, as it does now; a fast-rotating Venus would have quickly lost its oceans. But we have no idea what the early rotation rate was.

Venus may never have had an ocean. The young Sun may have vaporized any water, with the solar wind blowing away a steam atmosphere before it condensed on the surface.

Maybe Earth just lucked out. Life could be improbable, dependent as much on some absurd twist of fate as on specific planetary conditions, stages, or events.

So what do you think? I’ve made my best attempt to tell you why Venus should be dead — though I haven’t really convinced myself. In any case, I think it’s worth a look!

This article originally appeared in print in the May 2020 of Sky & Telescope.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.