Nearly 11 billion light-years away in the constellation Grus, astronomers have found an elongated clump of 36 galaxies that shouldn't exist. Most of the mapped space (green box, 300 million light-years wide) is empty of visible objects. The galaxies are clearly gathered in one particular part of the volume, for reasons unknown.

Courtesy NASA.

Yet another group of astronomers has found signs that we don't know as much as we thought about how galaxies formed after the Big Bang. An international team has located a streamer of galaxies 300 million light-years long that had already taken shape when the universe was only a fifth of its present age — at redshift 2.38, when the universe was just 2.8 billion years old.

Such a galaxy string would be no big deal in the present-day universe. It's similar to the famous Great Wall of galaxies just a few hundred million light-years away. But the best models of structure formation predict no gatherings so big appearing so early in cosmic history. "The universe was growing up faster than we thought it was," said Povilas Palunas (McDonald Observatory), one of the discoverers, at the American Astronomical Society meeting on Wednesday. "Our results are consistent with others that are coming from this meeting," he added, referring in particular to the recent discovery of big, mature galaxies that existed before theory says they should (see story below).

Team member Bruce Woodgate (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center) described how the astronomers first began to suspect something funny. They noticed two quasars 30 million light-years apart in the early universe showing spectral signs that the same, huge gas cloud was filtering the light of both. Gas clouds, even the ones that pervade galaxy clusters, shouldn't be that big. Further investigation turned up 36 galaxies and one quasar grouped at the same distance (redshift) in an even larger, ragged band at least ½° long on the sky. In fact the band runs off both edges of the field the astronomers surveyed. They intend to go back at the first opportunity and try to determine its full extent. They also plan to survey other patches of sky to see if such early structures are common.

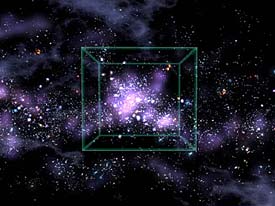

The galaxies in the image above are probably only the brightest tips of an iceberg; the region likely contains thousands more galaxies that are too faint to show, as depicted in this artist's concept.

Courtesy NASA.

All of the too-early galaxies and clusters that astronomers are finding do not, in any case, pose a crisis for cosmology — at least not yet. There's no reason to think the reigning Cold Dark Matter model of cosmic structure formation — a foundation of today's cosmology — is far out of whack. Galaxies and everything else made of normal matter are only a small part of the picture, and the brightest galaxies, the ones that show up over great distances, are surely only the tip of the iceberg. Most of the mass of the universe is in the form of unknown, nonbaryonic dark matter (matter not composed of atoms), which outweighs all normal matter by five or six times. What's apparently missing is a proper grasp of how gas gets funneled along the streams and clumps of dark matter into the pools that become galaxies, and how and when large numbers of the brightest stars begin to shine within the biggest of these. In today's universe, normal matter and dark matter are closely tied to each other — where there's one there's the other, at least on large scales — but early in cosmic history this probably wasn't so.

"We're looking at the galaxies; we're not looking at the mass," stressed team member Gerard M. Williger (Johns Hopkins University). "We'd love to look at the mass, but that's very, very hard."

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.