Last December, astronomers worldwide tracked a dramatic storm that erupted in Saturn's North Tropical Zone. Now two reports in Nature combine these observations with data from NASA's Cassini orbiter to show that the storm was triggered deep within Saturn's atmosphere and that it discharged titanic lightning bolts for days on end.

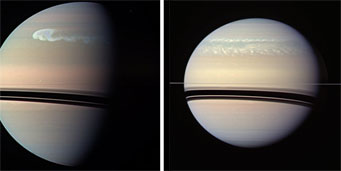

Images from Cassini taken on December 24th last year (left) and May 15th (right) show the progress of a massive storm in Saturn's atmosphere.

NASA / JPL / Space Science Inst.

Benign disturbances, dubbed convective storms, are common on Saturn. But storms 10 times more turbulent than these, called great white spots, can rage on the planet's face once every Saturnian year (29.5 Earth years). Only five such events have been recorded in the last 130 years.

The latest show began when Cassini's Radio and Plasma-Wave Science Instrument picked up signals of a lightning storm on Saturn. And even as ground-based observers watched the storm expand across 30deg;s of northern latitudes, with its eastward tail wrapping around the entire planet. Cassini recorded lightning flashes, called Saturn electrostatic discharges (SEDs), that were 10,000 times more powerful than those on Earth. A team of scientists led by Georg Fischer (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Graz) reports that the SEDs were clustered together, and that the action never did stop — at the storm's peak, the spacecraft recorded as many as 10 lightning discharges per second.

"Cassini shows us that Saturn is bipolar," notes Andrew Ingersoll (California Institute of Technology) in NASA's press release. "Saturn is not like Earth and Jupiter, where storms are fairly frequent. Weather on Saturn appears to hum along placidly for years and then erupt violently."

While these dramatic eruptions are commonly seen at the onset of northern spring, this storm began a little early on the Saturnian calendar.

Unlike Jupiter, which has only an axial tilt of 3.1°, Saturn's globe is tipped 26.7° to its orbit and thus has distinct seasons. As winter turns to spring, the changing insolation somehow causes water and ammonia to condense in the planet's atmosphere and creates moisture-laden convection cells that well up from the planet's interior. Scientists believed that these changes trigger the storms seen on the planet.

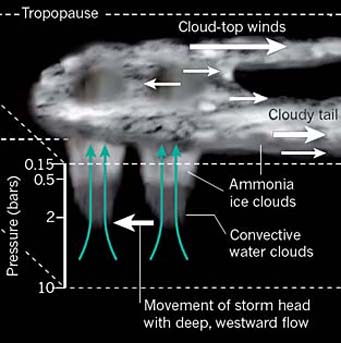

Studies indicate that convective upwelling of heat, moisture and ammonia from deep water clouds (originating at pressure levels of about 10 bars) into the upper troposphere produce the visible white clouds of Saturn's storms. A pair of eastward jet streams sandwich the eye of the storm and cause the formation of a fast-moving eastward tail.

Click on the image for a larger view.

Peter Read/Nature

The second report, by Agustin Sánchez-Lavega (Universidad del País Vasco, Spain) and others, concludes that the storm cells were generated 8 to 10 bars deeper in the planet's atmosphere than sunlight can penetrate. While the exact reasons for the convection currents still remain unclear, the authors suggest that great white spots can be generated when upwelling storm cells inject ammonia ice into the upper troposphere. The team used a series of telescopic images in ultraviolet and near-infrared wavelengths to map the eye of the storm within a westward jet stream at 38°N. It was sandwiched between a couple of eastward jets which might have caused the formation of a fast-moving eastward tail.

Scientists are still waiting to study the long-term changes precipitated by this storm, but the observations have already been game-changers for outer-planet specialists. As Peter Read (Oxford University) comments in an accompanying perspective, "It will be a major challenge for the next generation of atmospheric models to predict when and where storm clouds will next appear to brood over Saturn's normally bland and hazy face."

1

1

Comments

Nathalie Martimbeau

July 15, 2011 at 11:32 am

Hi,

I would like to find the source for the image taken on May 15 please ? I am searching the Cassini mission web page and can't find the press release for this image. I want to add it to our astro news segment at the Montreal Planetarium.

Best,

Nathalie

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.