Two weeks ago I traveled to Mexico, specifically to San Pedro Mountain Observatory (part of Mexico's Observatorio Astronómico Nacional), located 9,150 feet (2790 m) high in Baja California's San Pedro Martir National Park. Scientists from MIT's Planetary Astronomy Laboratory had enlisted me and four fellow members the Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston to make this trip.

The ride from San Diego to Ensenada and then on to the observatory is about 350 miles, the last 150 or so on twisting roads that hug the mountainsides. Fortunately we were under the care of professional drivers in the observatory's huge four-wheel-drive utility vehicles. This is not a drive I'd want to do in my Prius!

Bruce Berger

Our assignment was to carry specially designed CCD cameras to remote sites across both hemispheres to record the first-ever occultation of a star by a large Kuiper Belt Object (KBO). This kind of professional-amateur collaboration has worked well in the past for organizations like the American Astronomical Society, the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, the American Association of Variable Star Observers, and it proved to work well for MIT in this investigation.

My host for the two-day investigation was Raul Michel, a long-time staff member at the Institute of Astronomy at the Autonomous National Observatory (OAN) of Mexico. Dr. Michel specializes in cataclysmic variables. He has conducted many of his investigations using the same 60-inch (1.5-m) Ritchey-Chrétien telescope that we we'd be using.

Bruce Berger

Upon arrival I was assigned room 110 in the visiting astronomers' quarters. The room was quite comfortable, with a warm bed covered with several of those colorful wool blankets the Mexicans are famous for, private lavatory and shower, a desk, and wireless internet. Actually the wi-fi was available throughout the well-equipped building and in the observatories themselves.

Dr. Michel and I were assigned VW #5 in order to get around the steep hills of the observatory. The ride from our dormitory to the 60-inch telescope was about a mile uphill. After the first day Raul let me drive this 1998 Mexican-built classic. It brought back memories of the old VW from my college years.

Bruce Berger

We got right to work installing the camera on the telescope and testing it out in the daylight. We had a little trouble with the GPS unit but were able to get it stable enough for the night's work.

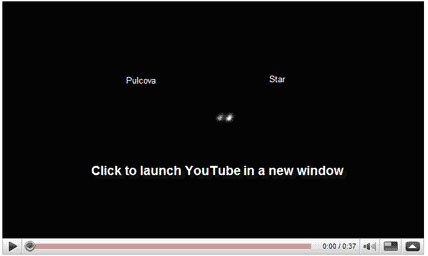

We were fortunate that timing was perfect for a practice run on the first night. The target was 762 Pulcova, a main-belt asteroid discovered in 1913 by Grigory Neujmin and named after the Pulcova Observatory near Saint Petersburg, Russia. Pulcova is a dark body 85 miles (137 km) in diameter, and it was to occult TYCO 2314-01655-1, a 12.2-magnitude star in Triangulum.

It's especially significant because in 2000 astronomers at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii discovered a small, 10-mile-wide moon orbiting Pulcova about 500 miles (800 km) away. This was one of the first asteroid moons to be identified.

Here I am bathed in red light at the base of the 60-inch, f/13.5 Ritchey-Chrétien telescope. It was installed at the SPM Observatory in 1970 in collaboration with the University of Arizona and the patronage of Harold Johnson. The original aluminum primary is on display at the UNAM Ensenada campus, where the new Cer-Vit mirror was ground and polished. At the lower left, an arrow points to the specially-designed CCD camera.

Bruce Berger

The telescope slewed and found our target star without trouble. I'd never operated at such a large scope so this was a special treat. As Dr. Michel calibrated the finder and guide scope, I switched on the camera and GPS timer. And there they were, both the target star and Pulcova.

Here”™s a video showing the occultation of TYCO 2314-01655-1 (at right) by the asteroid Pulcova (at left).Watch carefully as Pulcova moves in front of the star and emerges on the right.

Bruce Berger

Dr. Michel reduced the data contained in the 1,257 images that make up this light curve, which clearly shows the magnitude drop from 12.2 to 14.4 that we expected during the occultation.

Bruce Berger

Our "real" target would occult a 13.2-magnitude star the next night, or rather early morning, and this is what we were really here for.

We checked late occultation path predictions and learned that the revised path would be about 1,300 km south of us. But the uncertainty of the prediction was the reason we'd come here, because when combined with other observation reports, a negative sighting can help to define one dimension of the KBO.

Dr. Michel and I met at 1:30 a.m. (8:30 UT) and drove to the observatory. Our first goal was to attempt a long exposure to capture the KBO before the occultation started. Dr. Michel adjusted the telescope and focus, and then engaged the auto-guiding system. We took one 5-minute exposure, but the KBO was not visible.

Then I set the automated system to take one ½-second exposure every 1½ seconds starting at 10:07 UT.

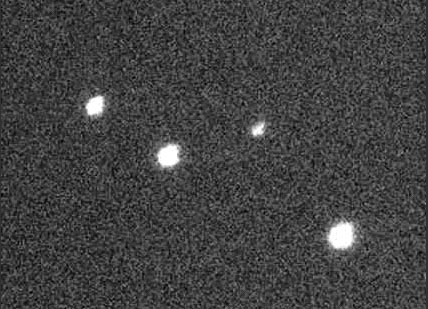

Right on time, our system started taking pictures of the occultation field. Our first shots came in, and they looked good. The Kuiper Belt object is invisible, but the star it was predicted to occult is the one at upper left.

Bruce Berger

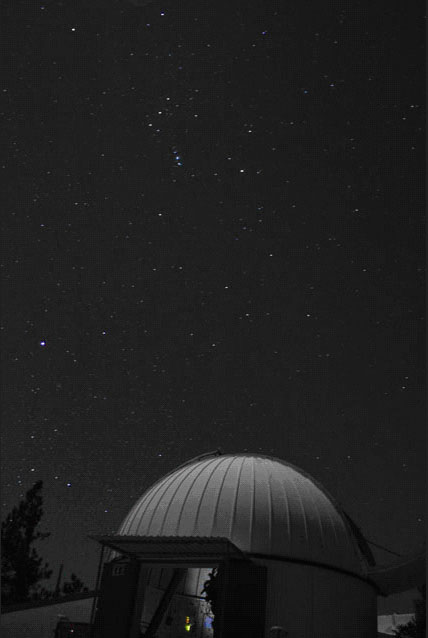

During all this I again set up my camera on a tripod while the shots were being triggered by the GPS receiver. While Dr. Michel monitored the telescope tracking from inside the warm control room, I set a pocket timer to 5 minutes and during each interval I would go outside the observatory and take in the beautiful night sky.

We took some focusing images and then waited for 10:00 UT to start our integrations. While we waited I set up a tripod and a Canon XSi DLSR inside the observatory and took some wide-angle sky pictures. The Moon peeks in at top center, and the Pleiades (M45) are clearly visible through the telescope's upper ring.

Bruce Berger

Orion is clearly visible in this 15-second exposure shot with the camera's lens set to 21 mm and f/4.0. The glow inside the observatory is from a laptop computer.

Bruce Berger

In all, we took over 2,000 images of the target star grouping between 10:07 and 10:56 UT, and then 100 bias shots and 30 flats. We've submitted our data and are excitedly awaiting reports from our host at MIT.

My very sincere thanks go to Dr. Michel and to the staff at San Pedro Martir Observatory, as well as to the supporting staff at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Ensenada, which I visited after coming down off the mountain.

Or, put another way . . .

Muchas gracias por la hospitalidad brindada durante mi visita al Observatorio Astronómico Nacional. Tuve una estancia muy buena y la comida y los telescopios se apenas a la derecha. Espero volver a SPM en otro momento.

This beautiful Brashear refractor is one of the several antique telescopes on display at the Ensenada offices of the 125-year-old Mexican National Astronomical Observatory (OAN).

Bruce Berger

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.