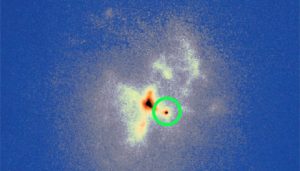

Astronomers have discovered an object in the active galaxy Cygnus A that wasn’t there before.

NRAO / AUI

Last week at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Grapevine, Texas, astronomers made an announcement that’s caught the interest of several researchers: a very bright something has appeared in a well-known galaxy.

That galaxy is the elliptical Cygnus A. Cygnus A is one of the brightest radio sources in the sky. It lies approximately 800 million light-years from us (redshift of 0.056). In its core sits a supermassive black hole madly eating and cocooned in gas, while two jets shoot out to either side and light up the intergalactic medium. This activity produces the radio radiation that makes Cygnus A so bright.

Using the recently upgraded Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico, Rick Perley (NRAO) and colleagues took a gander at Cygnus A — the first time the instrument has looked at the galaxy since 1989. (Apparently astronomers spent so much VLA time observing the galaxy in the 1980s that they didn’t feel the need to look again, Perley joked January 6th in his AAS presentation.) The new observations showed a surprise: a new, secondary object just southwest of the central black hole. This object wasn’t in the 1989 radio image. Additional, higher-resolution observations with the Very Long Baseline Array also picked up the object, clearly distinct from the galaxy’s nucleus. It’s roughly 1,300 light-years from the center.

The whatever-it-is is about twice as bright as the brightest known supernova at these frequencies. In fact, it’s much brighter than just about any transitory radio signal known, except for accreting supermassive black holes and tidal disruption events, outbursts created when a black hole eats a star.

The team scoured other archives and found the object in 2003 Keck infrared observations and, more iffily, in some images from Hubble. (The object is so red that it doesn’t show up well at optical wavelengths, and in this range the space telescope’s resolution isn’t as good as that of Keck’s adaptive optics.)

G. Canalizo et al. / Astrophysical Journal 2003

The science session’s attendees were aflutter with curiosity. Claire Max, who serves as director of the University of California Observatories (which manages both the Keck and Lick Observatories), went back and dug through Keck data and discovered that, in fact, astronomers had already discovered this source. In 2003 she, Gabriela Canalizo (now at University of California, Riverside), and colleagues had stumbled upon the mystery source. They, too, had gone back and found it in some Hubble images and not others — they weren’t sure whether that was because the source was flickering, or just that Hubble hadn’t looked long enough to consistently see it.

The team determined that the whatchamacallit wasn’t a foreground object in the Milky Way, nor a cluster of young stars in Cygnus A. Rather, it seemed to be a compact cluster of old, red stars, with all the trappings of being the stripped-down core of a much smaller galaxy that Cygnus A had eaten. That minor merger might also explain why the big galaxy’s black hole has “turned on,” the astronomers suggested in their 2003 Astrophysical Journal paper.

On the other hand, Canalizo and colleagues went on to suggest in 2004 that the source might instead be a peek at the hot inner rim of the dusty doughnut enshrouding the black hole.

Perley’s team favors a merger, too. But he advocated instead that the radiation might come from a second black hole, the leftover core of the eaten galaxy. If so, then Cygnus A is one of a few galaxies that seems to host a central binary black hole.

At the end of his presentation Perley called for others to look through their archival observations so that astronomers can pinpoint when this source appeared. His team is also looking in X-ray, but given that the central nucleus is so bright, they’re not optimistic of their chances of seeing something, unless there’s some variability. A formal paper and press release (with cool images!) are in the works, and when they’re out we’ll update you with more info.

References:

Richard A. Perley et al. “Serendipitous Discovery of a Radio Transient in the Luminous Radio Galaxy Cygnus A.” 229th American Astronomical Society. Abstract 319.06.

Gabriela Canalizo et al. “Adaptive Optics Imaging and Spectroscopy of Cygnus A. I. Evidence for a Minor Merger.” Astrophysical Journal. November 10, 2003.

Gabriela Canalizo et al. “Penetrating Dust Tori in AGN.” Penetrating Bars through Masks of Cosmic Dust. 2004.

Enjoy our blogs? Show your appreciation with a subscription to Sky & Telescope magazine.

2

2

Comments

Tom-Fleming

January 16, 2017 at 6:29 pm

From the article: If so, then Cygnus A is one of a few galaxies that seems to host a central binary black hole.

There are numerous examples of merged galaxies, some absorbing more than one. It is generally accepted that most galaxies host an SMBH. So the statement seems at odds with this fact. Is the existence of the absorbed galactic core a fairly transient event on the Universe's time line such that only a few are detectable at any given time?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Camille M. CarlislePost Author

January 17, 2017 at 9:53 am

True, there are numerous examples of merged galaxies, but there are far fewer examples of clear binary black holes in galaxies that are undergoing or have undergone a merger. By "clear binary black holes" I mean that we see emission/other signs from both black holes and they're within, say, 10,000 light-years of each other. Those are very hard to spot, and we don't have a whole lot of them. (Although, that number could be 100+ if all those discovered by http://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/new-evidence-for-black-hole-binary-1609201523/ are really binaries. In terms of those that are clearly binaries, the number is far, far lower.) Astronomers are very interested in finding more in order to test the merger-->black hole binary-->black hole growth idea.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.