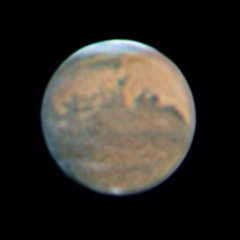

Mars on the evening of November 25th. The very dark band at right is Sinus Sabaeus, ending with the double prongs of Sinus Meridiani closer to center. Sky & Telescope assistant editor Sean Walker took this image at 2:43 on the 26th Universal Time using a webcam on a 7-inch telescope. North is up, as indicated by the North Polar Hood of clouds on the northern limb. A thin haze of dust has reduced the contrast of features in the southern hemisphere.

Image by Sean Walker.

Look high in the southeast to south these evenings and you'll see a big, yellow-orange "star" shining like no other. This is Mars. It passed unusually close to Earth during October and November 2005 and is still relatively close in December, though farther in January. Anyone can see it — no matter how little you know about the stars or how badly light-polluted your sky may be. There's nothing else so bright in its part of the sky.

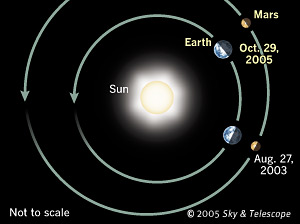

Mars is shrinking and receding into the distance as Earth pulls ahead of it in our faster orbit around the Sun. Even so, this is still a special time for Mars observers. At the end of October Mars reached a maximum apparent diameter of 20.2 arcseconds (the angular size of a penny seen from 620 feet). On December 1 Mars appeared 17" in diameter, on January 1 it's 12", and on February 1 it's 9". This compares with a maximum diameter of 16" during Mars's next opposition, in December 2007.

The orbits of Earth and Mars bring these neighboring worlds close together about every two years. For skygazers, the best meetings occur when Mars is near perihelion, the point on its elliptical orbit that's closest to the Sun, as was the case in 2003. This year's pairing, while not quite as good, is still very favorable and will be the best until 2018.

Sky & Telescope illustration.

Skywatchers at the latitudes of North America and Europe do have an advantage this season: Mars is far north in the sky and shines very high during evening, avoiding the thick layers of atmosphere that blur telescopic images of objects nearer the horizon.

Telescope Tips

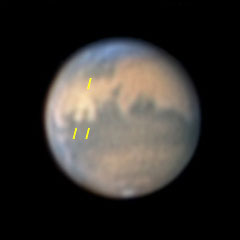

By October 18th, with summer advancing in Mars's southern hemisphere, a V-shaped dust storm had developed in the Chryse region. (Yellow ticks mark the upside-down V's ends and point.) Click on the image to see how the dust clouds changed and spread in the following two days. Mars observers were becoming concerned that the dust storm could grow and widen to blanket the whole planet, hiding surface features as happened at the Mars opposition of 2001. For this image, taken at 3:04 UT, Sky & Telescope assistant editor Sean Walker used a ToUcam Pro 740 webcam at f/50 on a 7-inch Maksutov-Newtonian telescope, then stacked the video frames using RegiStax freeware. North is up.

Photo by Sean Walker.

Surface details on Mars are always a pretty tough target in a telescope. To begin with, Mars is only about half the size of Earth. Even at its closest, under high magnification it appears as a surprisingly small, bright ball with some subtle dark markings, possible white clouds around its edges, and, currently, perhaps the tiny remnant of the white South Polar Cap shrunken in the warmth of the Martian summer.

Moreover, since mid-October 2005, dust storms on Mars have added a thin layer of yellow haze to the planet's atmosphere (at least in the southern hemisphere) reducing the contrast and visibility of surface markings.

The brightest yellow areas are deserts covered by fine, windblown dust. The darker markings are terrain displaying more areas of bare rock or darker sand and dust. Mars rotates once every 24½ hours, so if you can see detail at all, you can see Mars turning in just an hour or two of watching.

To see much detail, several things all have to be working in your favor. You'll need at least a moderately large telescope with high-quality optics. (For advice on how to select a telescope wisely, see "Choosing Your First Telescope"). And the atmospheric "seeing" must be good; this is the astronomer's term for the constant fuzzing and shimmering of highly magnified telescopic images due to the tiny heat waves that are always rippling through the atmosphere. The seeing changes from night to night and sometimes from moment to moment.

More about Mars this season, including a surface-feature map and a timetable of which side of Mars is facing us at any time, is in the September issue of Sky & Telescope.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.