In every batch of detections from the Kepler spacecraft, some transit signals get relegated to “false positive” status by an automated vetting pipeline. How do we ensure that real exoplanet detections don’t accidentally get discarded by the pipeline?

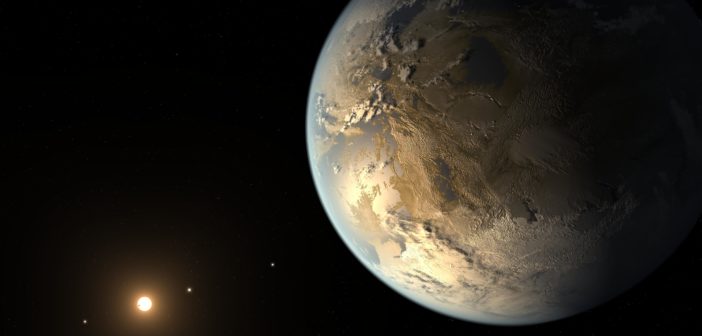

NASA Ames / SETI Institute / JPL-Caltech

The Kepler False Positive Working Group is on the case — and they just rescued quite a find from being relegated to a false-positive fate.

To Be a Planet Candidate

Since Kepler’s launch in 2009, this hard-working satellite has found signals from thousands of candidate transiting exoplanets. But all transit signals aren’t just immediately declared planet candidates!

The first hint in Kepler data of a potential transiting planet is what’s known as a “Threshold Crossing Event” (TCE). That TCE could either be a true signal from a planet transiting across the face of its host star, or it could be a false positive or false alarm — a signal mimicking a transiting planet that’s instead caused by a background eclipsing binary system, noise in the data, instrumental artifacts, etc.

Early on in the Kepler mission, every TCE was reviewed by a team of scientists and classified as a true planet candidate or a false positive. But as the mission ramped up and data volume grew, scientists turned to an automated pipeline — aptly named the Robovetter — to categorize the TCEs.

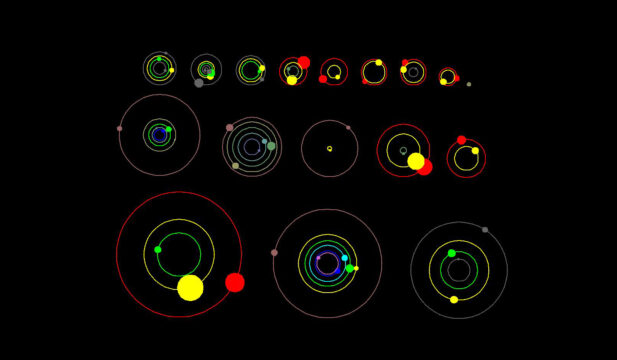

NASA Ames / UC Santa Cruz

Human vs. Machine

The automated approach has many advantages: we can process larger volumes of data, and the statistical uniformity allows us to make inferences about the sample completeness. But it’s inevitable that the Robovetter will sometimes be wrong, misclassifying a true planet as a false positive.

To address this, the Kepler False Positive Working Group was established to visually inspect all signals the Robovetter classified as false positives and confirm the categorization. This process allows us to improve the Robovetter’s algorithms — and it also opens the door to new discoveries hidden in old data.

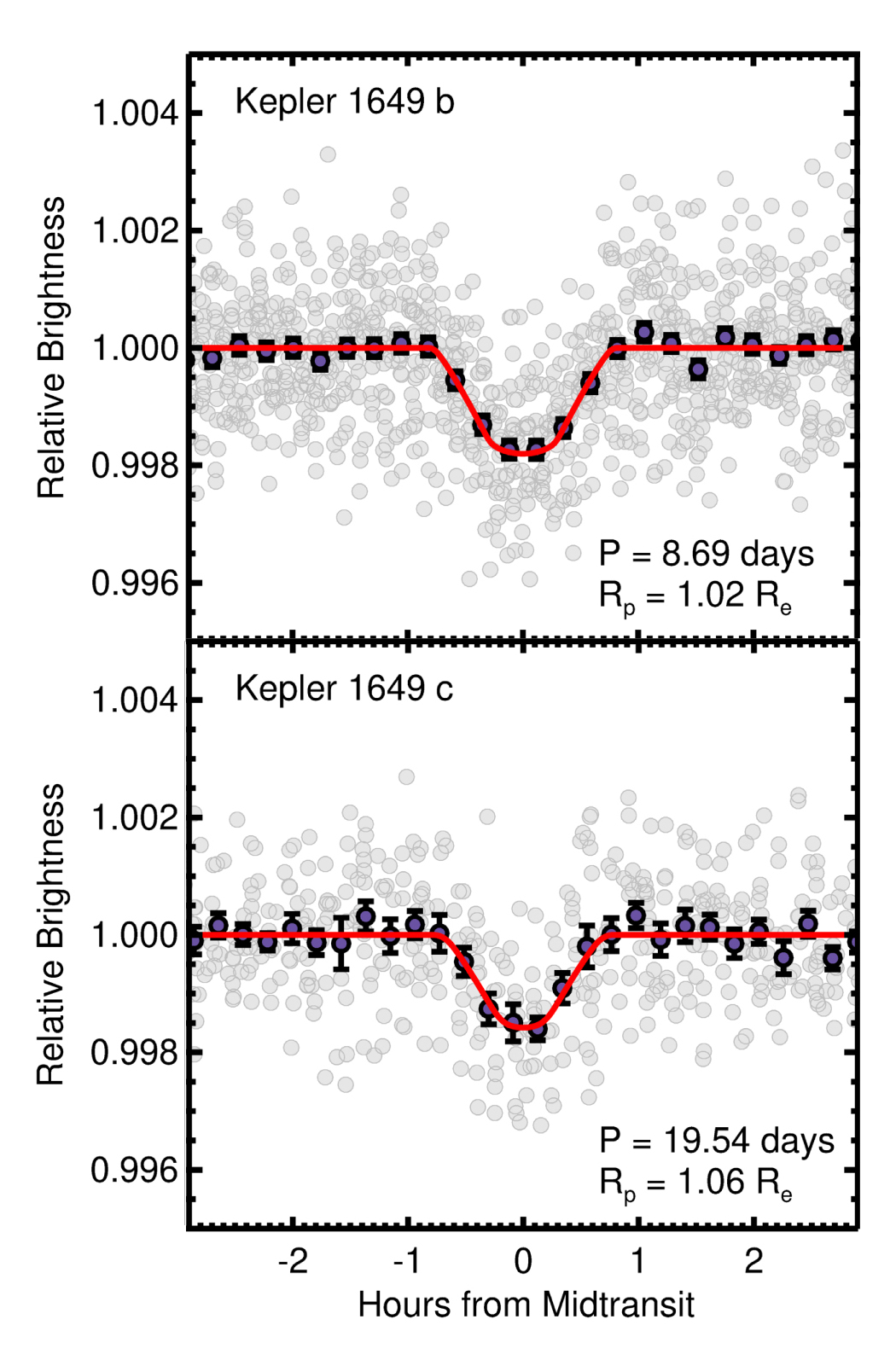

Adapted from Vanderburg et al. 2020

Such is the case with Kepler-1649c, a planet candidate that was incorrectly categorized by the Robovetter as a false positive. In a new study led by Andrew Vanderburg (NASA Sagan Fellow at The University of Texas at Austin), a team of scientists presents their rescue of this sneaky planet.

Earth-like Discovery

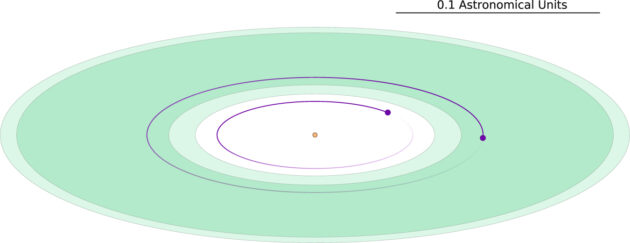

Kepler-1649c is a planet the same size as Earth that orbits around its M-dwarf host star once every ~20 days, placing it firmly in its host star’s habitable zone. Its star also hosts a previously known inner planet that appears to be equivalent to Venus in its size and the amount of flux it receives.

How did the Robovetter miss this important habitable-zone, Earth-like planet? Vanderburg and collaborators suspect that the pipeline was fooled into mistaking Kepler-1649’s location due to the star’s high proper motion. This introduced noise into the inferred light curve, making the Robovetter think the transit signal wasn’t real.

Vanderburg and collaborators point out that there are likely hundreds of undiscovered planets left in the extended Kepler mission data. While automated pipelines do a great job of doing the heavy lifting, the discovery of Kepler-1649c goes to show that there’s value in having a human eye checking results.

Vanderburg et al. 2020

Citation

“A Habitable-zone Earth-sized Planet Rescued from False Positive Status,” Andrew Vanderburg et al 2020 ApJL 893 L27. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab84e5

This post originally appeared on AAS Nova, which features research highlights from the journals of the American Astronomical Society.

2

2

Comments

Ken

April 28, 2020 at 1:44 am

This comment is totally irrelevant but needs airing.

Mathematical proof, the construct on which all mathematics and science is based. All it takes is one! One wrong conclusion, and everything that follows is false. There are many proofs, observations, and calculations which justify and even falsify the original flaw(s). Such are the errors of those that follow and such are the errors of Einsteinian physics and mathematics. The world awaits new genius to provide the insights, mathematics, and science to revolutionize our understanding of the universe.

I have always dismissed some of Einstein's theories. Nothing moves faster than the speed of light through space is a roaring example of mathematics based on wrong proofs. The supposition is false in that it is accepted to be true. It ignores our inability to imagine, measure, or conceive of any way to measure anything that might possibly exceed the speed of light. This is not proof that nothing can exceed the speed of light in space, it is only proof that our mathematics may be wrong. I am careful to use the term “in space” because current “knowledge” conceives of faster than light only during the Big Bang due to the fact that space did not yet exist, thus we rely on inflation to dismiss our mathematical models during this brief time period. Let us suppose that inflation always existed, and now exists even while space co-exists. Does the concept of inflation now become obsolete due to Einstein's narrow definitions of Space-Time or can new mathematical models incorporate inflation and faster than light in current observations of the universe?

I may not have the mathematics to prove, dis-prove, or question the current model of the universe, but let me state that I have a serious disquiet when it comes to the physics and mathematics that now describe the universe as we understand it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[email protected]

May 1, 2020 at 4:46 pm

Your first sentence is partially right - the comment is totally irrelevant. The rest is a waste of space-time and electrons.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.