Keeping a record of what you see in the telescope is not only fun but helps grow your observing skills. Learn how to start a journal and see how other amateurs keep theirs.

Bob King

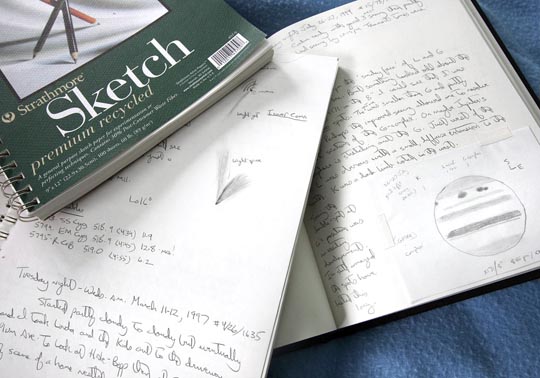

Do you write down what you saw after a session at the telescope? I've been doing it since I was a kid. I started my first diary at the tender age of 12. The loopy letters of my youth look funny to me now, but that little leather-bound book records highlights of my life when my hair was thick and heart beat strong.

Within its pages I recorded daily high and low temperatures, my first experience holding hands with a girl, and of course, short descriptions of the amazing things I saw through my 6-inch reflecting telescope at the time. I can't recall what motivated me to write, but the experiences were important to me. They meant something.

Bob King

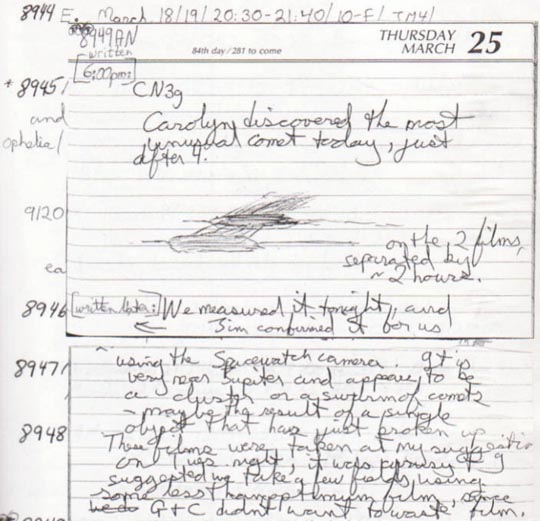

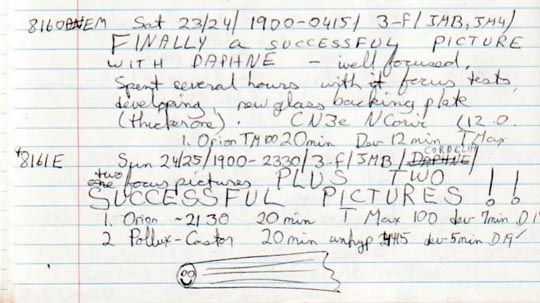

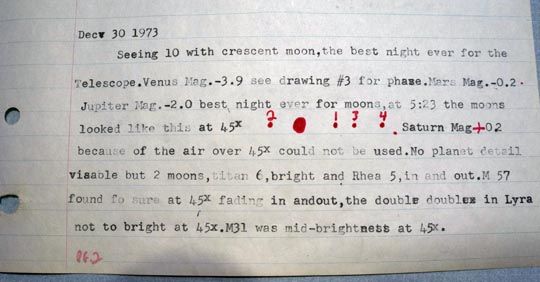

Much later in life, as responsibilities grew like dandelions, I abandoned the 3-times-a-day temperature readings. Cut out the daily ups and downs of life. But everything else goes in there — weather, the joy of spotting a long-sought comet, night sounds, failed attempts to find some faint galactic wisp, and sharing Jupiter with strangers passing by on snow machines. Now I've got boxes of large, black-bound journals bursting with sketches of planets, supernovae, the Sun, and auroras, along with descriptions of each night's explorations.

Elizabeth Warner

Some read back with the workmanlike tone of simple data recording; others capture the rhapsodic feelings so many of us experience when the sky gongs us with wonder, when we realize how our evanescent lives find a home in infinity.

Bernd Pauli

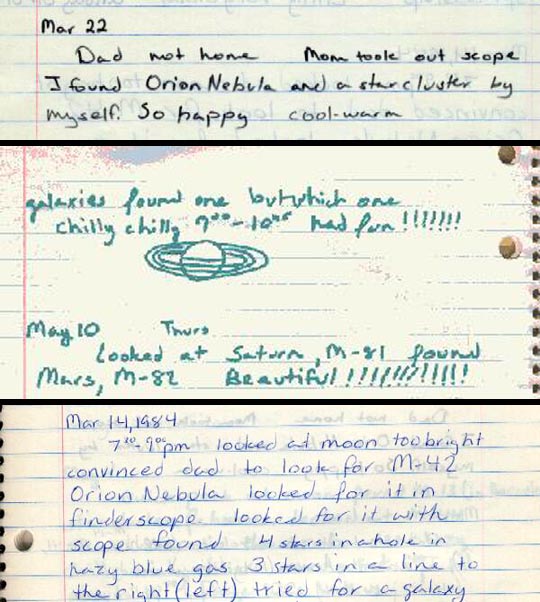

All these jottings. Maybe I'm crazy, but I've got company. Lots of company. Skywatchers the planet over happily put pen to paper or tap away at the keyboard to capture the stuff of their nightly journeys, too. How could you not record the story of how you finally found a long-sought galaxy or reveled in another's joy at seeing Saturn for the first time?

David Levy

David Levy

Most journals I've seen are brutally honest. We're OK admitting we tried but simply couldn't see that 14th magnitude planetary nebula. Heck, we'll go for it again another night. Was the night so cold you quit early because you couldn't take it anymore? Did a sound coming from the nearby woods scare the pants off you? Maybe you lacked an observing plan one evening, got tired, and returned to bed. All dutifully recorded.

Mike Sangster

One of the things I like about a journal is how easy it is to begin one. Buy a notebook, find a pencil, and you're ready to go. I usually take brief notes and make crude sketches at the telescope on a sheet of paper. Later, away from the mosquitos, biting cold and darkness, I sit down and more fully "illuminate" my observations in a notebook or bound artist's sketch book. Blank, unruled paper is your friend. You don't want parallel lines crossing through that lovely Jupiter sketch, do you?

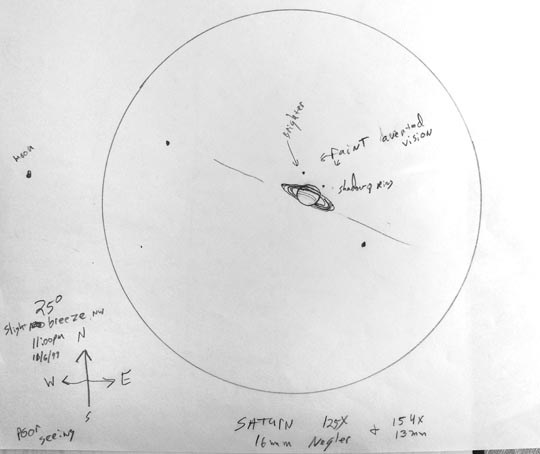

Jim Phillips

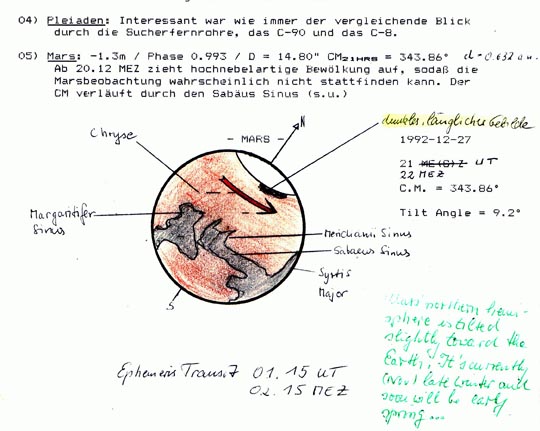

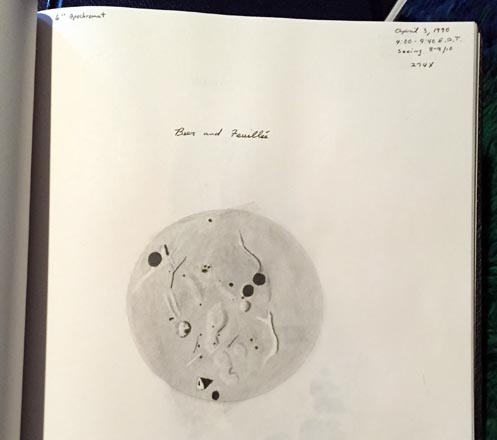

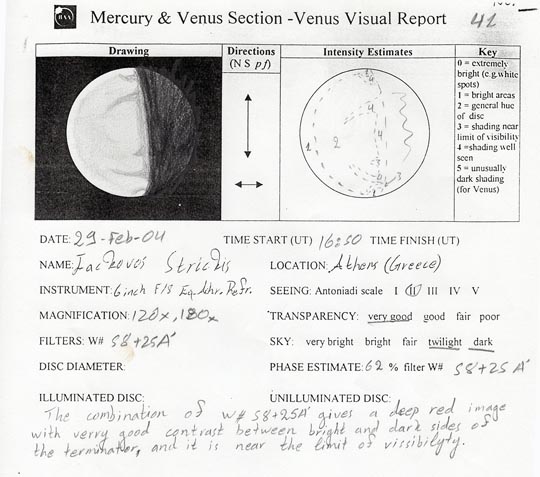

Start with the basics - day, date and time. Maybe a temperature, a brief statement about the weather, location, and telescope used. Then go on about what you saw and try your hand at sketching. I'm the worst artist on the planet, but I work at it. Now I can draw galaxies, comets and planets. But getting Saturn's rings just right still eludes me. Some organizations like the American Lunar and Planetary Observers offer convenient templates for each of the planets. These are much appreciated!

Lawrence Garrett

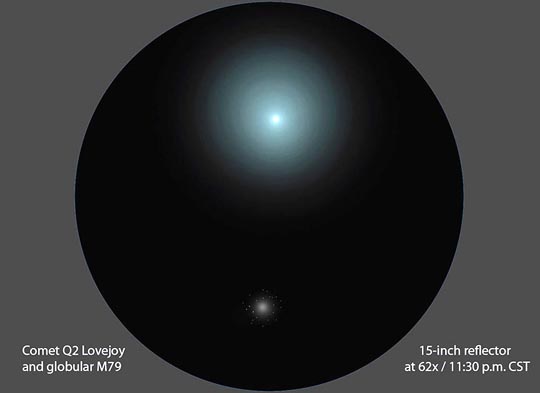

Some observers use color pencils for sketches, but many stick to a simple pencil. Depending on the pressure you apply, a pencil allows a broad palette of tones, while an eraser allows you to "sculpt" a drawing by judiciously removing bits and pieces of pencil smudging to delineate a galaxy's spiral arms for example. Of course, you don't even need a pencil. Lately I've been experimenting doing color sketches of comets with Photoshop using the dodge and burn tools.

Your verbal descriptions can be brief or as long as you like. Some skywatchers keep their logs tidy and organized, others not so much. If you make an observation of a short-lived phenomenon such as the brightness of a nova or variable star or appearance of a comet, record the time. You never know when you might catch a key event in an object's evolution. Should the call come for observations to help unravel its behavior, you might be in possession of a crucial data point.

There are many reasons to keep a journal. It's a low-pressure, low-tech creative outlet. Over the years it's fun to look back at your astro-adventures to relive a moment. Writing and sketching prepare the mind and eye to see better and more deeply the next time we step up to the telescope.

Taking time to write up an observation is a form of appreciation for the beauty that's all around us. The more we appreciate the world, the happier our lives. I want to thank all the amateurs who contributed samples of their work for this article.

For more on sketching and writing and journal writing, check out these links:

* Astronomy Sketch of the Day

* Cloudy Nights Sketching Forum

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.