S5 0716+71, a bright blazar currently in a feeding frenzy, invites you over for dinner the next clear night.

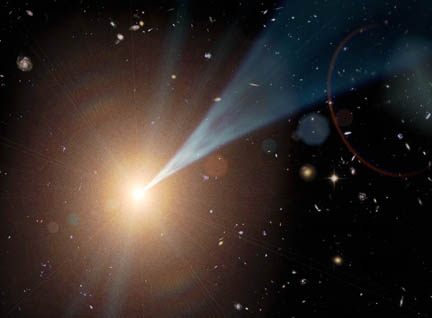

NASA / JPL-Caltech

Don't ask me to pick up the tab for S5 0716+71 — no way can I afford its voracious appetite. With no warning, this otherwise fastidious and faint stellar pinpoint in the circumpolar constellation Camelopardalis rose from magnitude +13.7 to +12.5 within a week. A sure sign it's feeding again.

The cause of this sudden surge in brightness is a supermassive black hole feasting on matter from its host galaxy, an invisible bit of fluff located 3.75 billion light-years from home in Camelopardalis.

S5 0716+71 belongs to a class of violently-variable, active galactic nuclei (AGN) called blazars. Like quasars, blazars begin with a supermassive black hole at the center of a distant galaxy feeding on interstellar dust, rogue planets, and the occasional stray star. As the doomed object falls into the gravitational trap, it's shredded, compressed, and heated to millions of degrees to join its cohorts in a swirling vortex or accretion disk centered on the black hole.

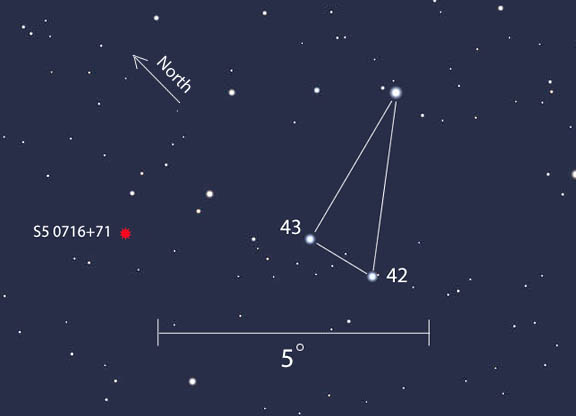

DSS2 / Stefan Karge

Much of the material within the disk ultimately spirals down the hole, but some of it gets whipped up by powerful magnetic fields generated within the rapidly spinning disk into a pair of relativistic jets. Any matter caught within a jet gets blasted hundreds of thousands of light years into space at 95 to 99% the speed of light.

We now understand blazars and quasars as two sides of the same coin: In a quasar, we view the AGN from the side; in a blazar we stare directly or nearly so into the jet. Observing a blazar is akin to someone shining a flashlight right in your face.

Because we see the jet almost square on, blobs of material within it can exhibit superluminal motion. As they travel toward us at nearly the speed of light, they keep pace with the light they emit. From our perspective, the difference in time of arrival between the two happens over a much shorter time frame, creating the illusion of faster-than-light travel. In October 2011, a team of astronomers observed a superluminal knot of material in S5 0716+71 traveling at an apparent speed ~21 times light speed!

ESO / M Kornmesser

In addition to their superluminal "powers," blazars exhibit time dilation effects, rapid variations in brightness, and even enhanced brightness due to relativistic effects. All this happens whenever S5 0716+71 encounters fresh material for gnoshing.

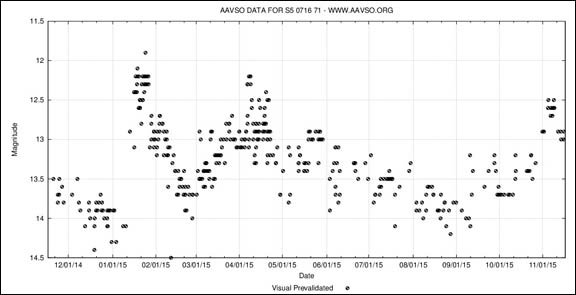

AAVSO

According to AAVSO data, the blazar reached magnitude +12.0, its brightest-ever showing in visible light, in January this year. A second outburst to magnitude +12.2 followed in early April; this November we're in the midst of yet another dinner-for-one production. Normally, the blazar glimmers weakly between 13th and 14th magnitudes.

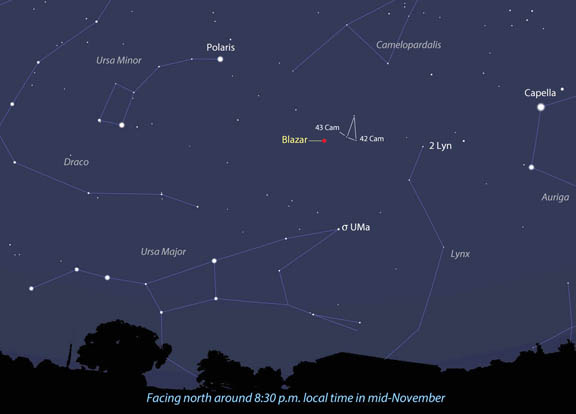

Stellarium

An 8-inch telescope currently shows it with ease; even a 6-inch might coax it out under dark, moonless skies with averted vision and a little patience. S5 1716+71 is located in a region devoid of bright stars, but on the up side, it's circumpolar and visible almost any time of night from much of the United States, Canada, and Europe. I usually set the scope up around 8:30 p.m. local time, when it's climbed about the mass of conifers that line my driveway.

Stellarium

This past weekend (Nov. 13-15), the blazar held steady at magnitude +12.7-12.8, but I see it's now beginning to fade (Nov. 18). Will that trend continue or will it reverse course and flare brighter yet? That's half the fun. Regular monitoring of S5 0716+71 brings its own rewards and a chance to be one of the first to catch it during the next outburst.

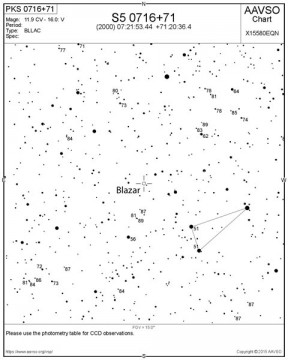

AAVSO

To reference its ups and downs, I encourage you to download the free charts of the blazar available from the AAVSO. The pinpoint-accuracy maps also include nearby field stars and their magnitudes which you can use to estimate the object's brightness. If you find yourself in the habit of making brightness estimates, consider joining the association and sharing your observations with amateur and professional astronomers worldwide.

To make a chart, type S5 0716+71 in the Pick a Star box then click Create a Finder Chart. You can either accept the chart shown or click Plot Another Chart. Many options are available.

I confess a love for theoretical astrophysics, a science which uses theoretical models and computer simulations to understand phenomena as diverse as the flow of gas around a black hole to the beginning of time in the Big Bang.

I'm no astrophysicist. Not by a long shot. But thanks to those who are, we can picture and understand the mind-boggling scene that goes by S5 0716+71 when it snaps into focus in our telescopes.

Resources:

* Detailed AAVSO finder chart with stars to mag. +13.5 to precisely locate our featured blazar

* Stefan Karge's Franfurt Quasar (and Blazar) Monitoring

* AAVSO blazar list

7

7

Comments

Frank-ReedNavigation.com

November 18, 2015 at 2:42 pm

Another terrific story from Bob King.

Despite being so faint, this is a great object for a quick peek with casual observers. Distance alone is worth it. The light we see tonight from that little speck on the camel's back left there when the last of the lunar maria were being formed at the very end of the Late Heavy Bombardment, and the surface of the Earth was still a kind of hell...

By the way, there's a little trick with WordPress-based web sites like this one that I think is worth passing along. The caption here for the AAVSO finder chart says to "click to download a large version". Well, sort of. This is browser and screen-dependent, and in many browsers, e.g. Chrome, Firefox, clicking only yields a popup with another view of the image that is only a bit larger (depending on available screen real estate). The trick is to right-click (option-click) on the popup image. Then you can select "save" or "open in new tab" or various other options that show the full-size image.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

November 18, 2015 at 7:52 pm

Thank you very much, Frank! And thanks for the lunar maria perspective and the "little trick". We appreciate it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tom Hoffelder

November 20, 2015 at 2:05 pm

Frank, excellent comments! I would like to add that even though Earth was a kind of hell 3.75 billion years ago, it was surprisingly a kind of "living hell" since many biologists agree that life (along the lines of a bacterium, not a simple virus) first appeared "somewhere between 4.1 and 3.9 billion years ago, or [only] some 0.5 to 0.7 billion years after Earth originated." (Rare Earth: Why Complex Life Is Uncommon in the Universe, by Peter D. Ward and Donald Brownlee, 2000

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tom Hoffelder

November 20, 2015 at 1:35 pm

Thanks very much for posting this! It's just what I've been needing: some really "deep sky" targets for my C14!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

November 20, 2015 at 7:17 pm

Could you please explain what gnoshing is?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Adlhoch

November 23, 2015 at 4:58 pm

Bob, thanks for the great article! I was actually on the S5 team back in the 1980s. I was an astronomy undergrad at the University of Arizona, working for Helmut Kuhr (the principle investigator). My job was to attempt to correlate the radio sources with visual objects on the old glass POSS plates. I also accompanied him several times to various telescopes on Kitt Peak to collect visual spectra of the S5 objects. That was probably the second best job I ever had! I'm not in the field any longer, but still an avid amateur. After reading your article I plan to find 0716+71 with my 20" dob and say hello to an old friend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tom Hoffelder

December 1, 2015 at 9:53 am

After reviewing the Frankfurt list, I'm much more interested in PG 1634+706. At mag 14.2-14.7, it is always in range of my C14, and 3963 Mpc is 12.9 Gly! It seems difficult to believe that something that distant is always bright enough to be seen in a 14, but I'm assuming (and hoping) the numbers are correct.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.