A nearly full Moon offers plenty to see and ponder.

This week the lunar disk transitions from a fat, waxing gibbous to full on Saturday night/Sunday morning (February 8/9). Some won’t be able to resist calling this full Moon a “supermoon.” The phrase gets dragged out any time the full Moon coincides with our satellite being near perigee, but in fact, the Moon will actually be closer to Earth for the full Moons in March, April, and May.

Much more interesting is how high in the sky our nearest celestial neighbor appears at this time of year, and how that can effect one’s perception of the nocturnal world.

When I was a kid, I’d often wake up late at night and go to our big dining room window to look out into the yard. One winter night, as I took in the bright, moonlit scene, I was struck by a feeling of warmth — as if I could step outside and experience summerlike conditions. The impression was powerful. Years later it finally occurred to me what was going on.

As I absorbed the backyard scene, subconsciously I registered the appearance of the trees and the shadows they cast — these were not the long shadows of a cold, winter’s day, rather, they were the stubby shadows cast on a summer afternoon. Hence, the remarkably vivid sensation of warmth I experienced that night.

High Moon

Stellarium, with additions

Most skywatchers know that the full Moon rises around the time the Sun sets because it’s positioned opposite the Sun in the sky. Less well appreciated is that the full Moon is also about 180 degrees from the Sun along the ecliptic, which is to say, the full Moon is always found about where the Sun will be six month’s later. On the winter solstice, the Sun sits low in Sagittarius and the full Moon rides high in Gemini — which is why the light of winter full Moon mimics that of the summer Sun.

If you’re a lunar observer like me, you try to catch the Moon when it’s highest in the sky and minimally affected by atmospheric turbulence — what stargazers refer to as “seeing.” The most northerly point on the ecliptic is in Gemini, about 5° west and a little north of 2.9-magnitude Mu (μ) Geminorum. But really, any time you find the Moon near the meridian and in the stretch of the ecliptic extending eastward from northern Taurus, through Gemini and into Cancer, you’re going to enjoy near-optimal viewing conditions.

Throughout the year, different phases of the Moon appear in this prized zone. As February begins, that phase is a waxing gibbous — the phase the Moon is until it turns full on the weekend. At that point, the Moon slips over the border from eastern Cancer into Leo.

Telescope Treats

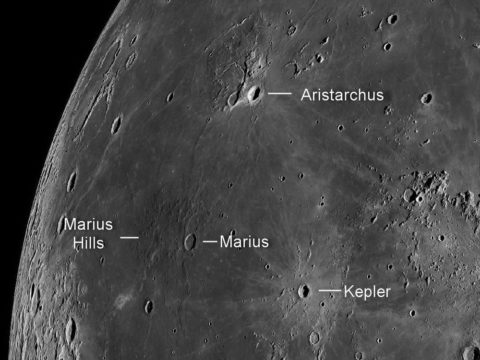

Although some telescope users might regard the nearly full Moon as the least interesting phase, if you focus your attention on the advancing terminator you’ll find lots of fascinating lunar features to inspect. I’ll be aiming my scope at the craters Aristarchus, Schickard, Bailly and Grimaldi. In addition, take advantage of the favorable illumination conditions on Wednesday and Thursday nights (February 5 and 6) to check out the Marius Hills. The Hills area collection of tiny, volcanic domes located south of Aristarchus. These suggestions are just a few of the highlights on offer a during high Moon this week.

Further Reading

Full Moon Is Tycho Time by Bob King

Observing the Full Moon by Charles A. Wood

0

0

Comments

Charles-Keller

February 5, 2020 at 5:10 pm

Love this article. Even as an adult, I still enjoy seeing the shadows cast by the full moon and thinking about the sun's placement on the ecliptic in six months - or six months past. Obviously works for other phases, too, with only a little math applied.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.