A deepest, darkest sky offers an extraordinary encounter with the stars.

There are different experiences of awe or great wonder in astronomy. The most staggering and momentous, I believe, comes during a total eclipse of the Sun. But the most peacefully (yet still stirringly) wondrous is the sight of a clear, dark sky filled with stars.

Perhaps the best sky of this sort was one I observed 40 years ago this September.

Early autumn’s limit-pushing clear nights

Across most of the contiguous United States, the least cloudy time of year runs from about late August through mid-October. Strong cold fronts move through frequently but briefly, temporarily pushing away clouds and haze. Here where I live in rural southern New Jersey, a favorably placed “omega block” weather pattern sometimes produces extremely transparent nights in late April or early May. But some of the clearest and therefore most star-crowded nights I’ve experienced occurred in September or early October.

Stars to 8.0?

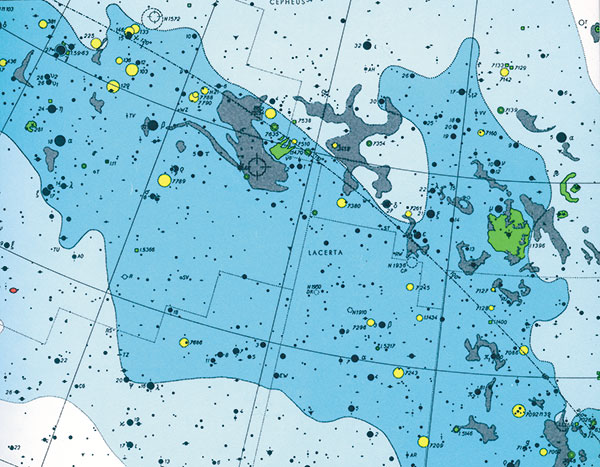

Take a look at our October all-sky map on page 42 (October 2017 issue). The bright stars from northeast to southwest resemble a wave sweeping the Milky Way band across the sky. But filling the entire southeast quarter of the heavens is a flood of sky so sparse in bright stars it really does deserve to be compared to a dark ocean (and because it consists entirely of water-related constellations, it’s often called “the Water” and the “Great Celestial Sea”).

Fomalhaut and Beta (β) Ceti (also known as Diphda or Deneb Kaitos) are the only stars of 2nd-magnitude or brighter in this region on our map — if we consider the non-aquatic Epsilon (ε) Pegasi (Enif) and stars of the Great Square of Pegasus as merely bordering the region. But what about the interior of the Great Square? Only two stars inside its huge pattern are bright enough to be plotted on our map. What a joy it is to have a sky dark and clear enough to make this quadrant of the sky crawl with countless faint stars.

That night in September 1977 I was easily seeing stars in the magnitude 6.76 to 7.25 class of Antonin Becˆvárˇ’s Skalnaté Pleso Atlas of the Heavens with my 22-year-old naked eyes. I tried for a very faint but conveniently situated star from the atlas — and finally convinced myself I was seeing it. I looked up its brightness in the SAO Star Catalog — magnitude 7.9! But not many years ago I checked its brightness in a more recent database — its brightness rounds off to 8.0. And this observation was from just 40 feet above sea level. Did I really see the star? Other sights I was seeing (including M52 with the naked eye) suggest that I did.

Totality and the positive opposite of fear

Many years ago, a local newspaper ran an article about a rare southern New Jersey tornado that struck the grounds of a prison about 10 miles from my home. The tornado destroyed a huge barn (I went to inspect the ruin) and tossed one of the prison guards 50 feet through the air. But it was the words of another prison guard that struck me the most. He said seeing the tornado headed right toward him was “the kind of sight that makes strong men weak.” So too is a total eclipse of the Sun — in the opposite way.

What do I mean? There are different kinds of opposites. One opposite of fear produces similar and equally strong feelings and sensations — but is positive, not negative. That emotion is, of course, awe. And if you experience a total eclipse of the Sun with even the least sensitivity to the wonders of nature, you’ll be swept away by your awe of the event. In fact, I hope many of you have been swept away by the time you receive this issue — maybe around August 21st?

This article originally appeared in print in Sky & Telescope's October 2017 issue.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.