The author wonders whether other worlds produce creatures who create art.

I’ve recently spoken at several art museums in conjunction with the current tour of “NASA Art: 50 Years of Exploration.” The diverse range of artistic responses provoked by the space age, from Rockwell to Warhol, is both inspiring and dizzying. And as spacecraft continue their reconnaissance, artists will continue to find new ways to help us assimilate the experience.

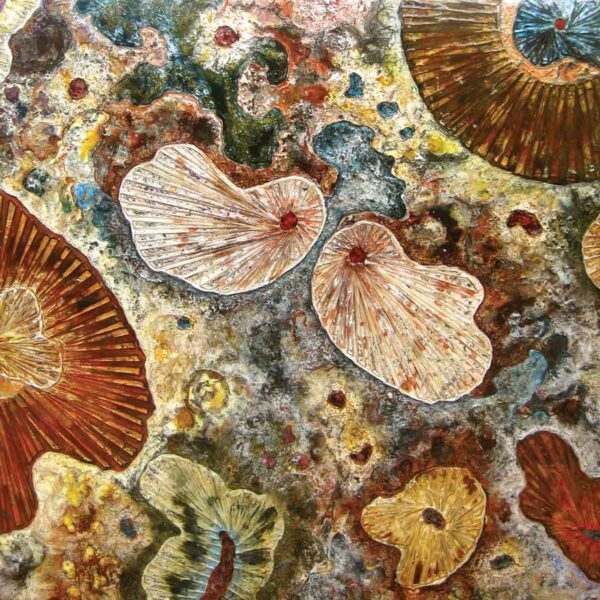

In Colorado Springs the NASA show was paired with a major exhibition by Monica Aiello, a Denver artist who finds inspiration in the moons of Jupiter, mimicking or riffing their colored surfaces with materials and techniques that do not so much faithfully resemble the landscapes as evoke deep responses to them.

But is there art on other planets? In one sense, obviously yes. Certainly we find artistic qualities in the bursting flowers of Ionian volcanoes and the tangled roots of Europa’s cracked, icy surface. But why?

Theories about art are like theories about life. Volumes have been written about the search for life even though nobody can define it well. Of course Earth is beautiful to us and aesthetically evocative; our senses and minds evolved in response to it. But what about planets, where no ancestor of ours has ever laid eyes or set foot, root, or cilia?

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the places in our solar system that seem most promising for astrobiology are also the most aesthetically evocative. Mercury and the Moon are dead; they are scientifically important but not as artistically inspiring as Titan and Mars. Energy flow and activity, phase transitions and complexity — these make for the most beautiful places, the most interesting to explore, and the most likely to produce life.

In this vast galaxy, which we now know is well populated with planets, will such active worlds occasionally produce other art makers? Our cultures are born of sym- bolic languages, including the creating of art in every human society. Now that chimpanzees, crows, and octopi have been found to also use tools, what is unique about us? Archaeologists use the presence of art in ancient sites to distinguish humans from non-human ancestors. Art making seems so widespread, so intertwined with our other unique capacities, that it makes me wonder if it might be universal — inherent in the evolution of curious, communicating civilizations. Or is it some local evolutionary peculiarity of our brains? I’d like to think it’s something deeper than that, but as a scientist I’m obligated to be particularly suspicious of any thought that I would like to be true.

We often focus on the ability to build machines, and in particular radio telescopes, as the hallmark of extraterrestrial intelligence. This is pragmatic but perhaps suspect, since this criterion was invented by radio astronomers. We debate whether intelligence inevitably produces science and technology. We cite dolphins, swimming and singing with big brains but too streamlined for opposable thumbs, as an example of intelligence without technology. Dolphins don’t create brick-and-mortar art, but do they have something analogous to choral music or poetry?

Perhaps, like life or intelligence, extraterrestrial art is something that we can’t define but can still search for and hope to recognize and understand. This leaves room for misunderstandings of cosmic proportions.

This article originally appeared in print in the August 2011 issue of Sky & Telescope. Subscribe to Sky & Telescope.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.