How many of you can claim that your favorite stargazing spot is as dark now as it was five years ago, let alone 10 or 20? That's what new measurements show for Kitt Peak in southern Arizona — terrific news for the largest collection of professional observatories in North America.

Kathryn Neugent and Philip Massey of Lowell Observatory took a series of 30 night-sky brightness readings in 2009 and 2010 from Kitt Peak's 6,880-foot (2,097-m) summit. They aimed their photometer straight up and also angled it in the directions of Tucson, Phoenix, Nogales, and "Nowhere" (due south). Then they compared their readings with those made by Massey in 1988 and 1999. Their research appears in October's Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

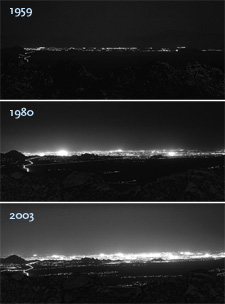

As seen from atop Kitt Peak, the lights of Tucson, Arizona, dominate the northeast horizon. But, thanks to strict lighting codes, the city's growth over time hasn't affected the sky's darkness over the summit. Click here for a larger version.

B. Schoening / J. C.Golson / M. Hanna / NOAO

"Overall," Neugent and Massey conclude, "the sky brightness has remained remarkably constant over the past 20 years." In fact, the raw data show that the sky directly overhead at the summit is actually a little darker than it was a decade ago. Apparently, they realized, the ongoing minimum in solar activity has reduced airglow (fluorescing oxygen atoms) in the upper atmosphere significantly compared to that during 1999's solar maximum. Still, after applying a correction, the Lowell duo finds that the sky at the zenith is only about 0.1 magnitude (10%) brighter now than it was in 1988.

It's all the more remarkable considering that the population of Tucson, just 40 miles to its northeast, has grown by more than a third in the last two decades and now tops a half million. Even the measurements made lower down in the sky, toward the city, show that sky brightness has remained steady over the past decade, after increasing 0.3 magnitude in the 1988-99 interval.

So what gives? The answer is decades of municipal arm-twisting. Astronomy is big business in Arizona, having built up a billion-dollar infrastructure that pumps $250 million into the state's economy annually. So there's incentive to keep the dark skies dark. (Let's not talk about Phoenix, shall we?)

A 1993 aerial photograph of the observatories atop Kitt Peak in southern Arizona.

NOAO / AURA / NSF

Over the years astronomers as the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, headquartered in Tucson, have worked aggressively to preserve the pristine darkness at the summits of Kitt Peak and Mounts Lemmon, Graham, and Hopkins. In response, local officials first imposed outdoor-lighting restrictions in 1974. Subsequent revisions in 1987, 2000, and 2005 have created night-lighting codes shared by Tucson and the surrounding Pima County that are among the toughest in the U.S.

The Tucson-Pima regulations do more than simply require new or replacement lighting to be fully shielded, so that no light is emitted above horizontal. There's also a set of "lumen caps," which limits how much outdoor light is allowable for a given-size property, and strict curfews. Moreover, Tucson is one the last bastions of low-pressure-sodium (LPS) fixtures, which emit just a single wavelength of yellow light that's easily avoided by astronomers making spectroscopic observations.

While all of these contribute to keeping Kitt Peak's skies luxuriously black, shielding may well provide the linchpin. In a study published in Physics Today last December, Chris Luginbuhl (US Naval Observatory) and two others found that light straying out a fixture at angles just above horizontal can affect the skyglow for more than 100 miles (200 km) in all directions.

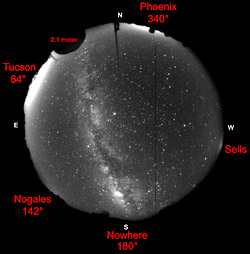

A fish-eye image taken June 13, 2010, with Kitt Peak's all-sky camera shows light domes visible from the summit (numbers give their azimuth directions). Tucson is 55 miles away, and Phoenix is 120. Click here for a larger version.

K. Neugent & P. Massey

The new findings come at a crucial time for NOAO, which is trying to maintain Kitt Peak in the game for funding and observatory development. Buell Jannuzi, who recently stepped down as director of NOAO's Kitt Peak National Observatory, believes the entire community — officials, businesses, and the Tohono O'odham Nation (whose land includes Kitt Peak) have shared in keeping the skies dark. NOAO's press release about the sky test, he says, spreads the word that the strict lighting curbs are paying off and provides ammunition for city officials looking to keep them in place.

Meanwhile, Tucson itself isn't quite the dark-sky haven it used to be. Jannuzi remembers being able to see Halley's Comet and the Milky Way from within the city limits. But much of light pollution (like politics, Tip O'Neill once famously said) is local. All that population growth has created a stronger pall of skyglow over Tusconans' collective heads.

Still, it's nirvana when compared the starless skies over most other cities.

1

1

Comments

richard.norman

September 30, 2010 at 1:48 am

The difference in sky glow is obvious! Just print a black bar across the images to see the difference in the sky glow between 1953 and now!

If you can see the light source with a camera from above the light source, guess what?... the light source is contributing to the sky glow!

In the 1950's, Dr. Wernher von Braun helped a local high school student, Mr. Sammy Pruitt, choose the Monte Sano State Park for our observatory not just for its elevation, but because it was a remote dark site! Currently the Rocket City is struggling to maintain our view of the Milky Way!

How are we to inspire the youth of the community to explore space when they can't see the stars ?!

Thank you for your effort, and I hope you have a Stellar Night!

Sincerely,

Richard Norman

Dark Sky Rep

Von Braun Astronomical Society

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.