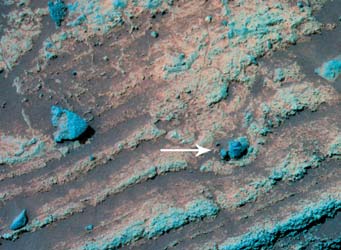

The ripples under this 4-centimeter "bomb" suggest the rock likely landed into ancient Martian mud.

NASA/JPL/Caltech/USGS/Cornell

Is there anyone out there who still doesn't believe that ancient Mars was once very wet? Can we see a show of hands? Well, for all you skeptics still in the room, two recent announcements might change your opinions.

The first was hinted at back in October 2006 at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences meeting and the refereed results appeared in the May 4th issue of Science. At his presentation, Mars Exploration Rover lead scientist Steve Squyres (Cornell University) showed this close-up piece of Home Plate, the largest exposure of layered bedrock that the Spirit rover has yet found as it roams the floor of huge Gusev Crater. In this false-color view, a 4-centimeter rock (arrowed) appears to have deformed the layers beneath it.

“That’s a bomb sag,” says Squyres. To geologists, a bomb is a rock that falls from the sky. If it lands on soft layers, you see something like this. And it’s a big clue. “The fact that it’s a bomb sag says there was some kind of violent emplacement process, some kind of high-energy process,” notes Squyres. Given the geochemistry of the rocks in the area, a volcanic origin (rather than, say, a meteorite fall) is the most likely cause.

The water evidence comes from those deformed layers. A great way to blast basaltic rocks into the air is by volcanic steam explosions. And, says Squyres, “If you saw a bomb sag like this on Earth, you would say those sediments were wet — like soft, deformable mud.”

This brightly colored silica-rich soil, plowed up by the Spirit rover, almost certainly formed in the presence of liquid water.

NASA/JPL/Cornell

The second piece of evidence was released early this week on the NASA rover website. The team unveiled a concentrated deposit of non-crystalline silica. After analysing the patch with the Spirit's thermal emission spectrometer and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, the rover team learned that the bright-toned feature is so rich in silica (about 90%) that the process forming it almost certainly required the presence of liquid water.

“The fact that we found [this] after nearly 1,200 days on Mars . . . makes you wonder what else is still out there,” says Squyres.

Anyone else still raising their hand?

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.