The Tadpole Galaxy, UGC 10214.

Courtesy NASA and the ACS Science Team.

Jubilant astronomers and NASA officials unveiled the first images from the Hubble Space Telescope's Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) today. The strikingly detailed and colorful vistas reveal never-before-seen features in celestial objects both familiar and obscure.

Installed by shuttle astronauts on March 7th, the ACS is Hubble's first new visible-light camera in nine years. Compared with the telescope's workhorse, the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2, the ACS covers more than twice as much sky with sharper resolution and higher sensitivity. Its 17-megapixel detector array records a patch of sky 3.4 arcminutes square, about one-ninth the apparent diameter of the Moon.

The picture above captures an unusual 15th-magnitude galaxy cataloged as UGC 10214 and known informally as the Tadpole. Located about 420 million light-years away in Draco, the

object is a gravitationally disrupted spiral. Its debris tail, stretching 280,000 light-years to the east-northeast, was presumably drawn out by tidal forces during a collision with another galaxy, the blue remnants of which shine through the spiral's disk at upper left. The interaction is playing out against a rich backdrop of remote galaxies — as many as 3,000 of them — seen with unprecedented clarity. The image is reminiscient of the twin Hubble Deep Fields, which snared thousands of galaxies in 100-hour exposures. But this picture, constructed from images made in near-infrared, orange, and blue light, required only 8 hours of exposure time.

The Mice, NGC 4676.

Courtesy NASA and the ACS Science Team.

The ACS image at right shows a spectacular pair of colliding galaxies 300 million light-years away in Coma Berenices. Officially known as NGC 4676, the pair are nicknamed "The Mice" because of the long tidal tails of stars and gas projecting outward from the maelstrom. Computer simulations suggest that the centers of the two systems were closest together some 160 million years ago. In the far future the pair will merge into a single giant elliptical galaxy. Astronomers predict that a similar fate awaits our own Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, M31. This composite-color image is assembled from exposures made through near-infrared, orange, and blue filters.

The Cone Nebula, NGC 2264.

NASA and the ACS Science Team.

A favorite target of deep-sky photographers, the Cone Nebula (NGC 2264) in Monoceros lies within a turbulent star-forming region about 2,500 light-years away. In the image at left, the ACS has zeroed in on the upper 2.5 light-years of a 7-light-year-long pillar of gas and dust at the apex of the Cone. Radiation from hot, young stars out of the frame at top is eroding the pillar and causing the hydrogen gas to glow crimson. The vivid three-dimensional scene recalls Hubble's famous image of the "Pillars of Creation" in the Eagle Nebula, M16. This view is a composite of near-infrared, hydrogen-alpha, and blue-light exposures.

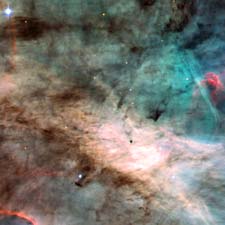

The Omega Nebula, M17 (detail).

NASA and the ACS Science Team.

The Omega Nebula, M17, is one of the easiest deep-sky objects to find in binoculars or a small telescope. Roughly 5,500 light-years away in Sagittarius, this mottled, hollow cloud of gas and dust is energized by intense ultraviolet radiation from young, massive stars beyond the upper-right corner of the ACS close-up at right. The blistered walls of the nebula shine with the light of excited atoms and ions. For example, the rose-like feature just right of center glows with the telltale hues of hydrogen and sulfur. This composite-color view is constructed from exposures made through four filters: blue, near infrared, hydrogen-alpha, and doubly ionized oxygen.

"We have a great camera!" enthuses ACS team leader Holland Ford (Johns Hopkins University). He expects to show off more ACS images at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in early June. Around that time, other Hubble astronomers will unveil new results from the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS), which was idled three years ago when its coolant prematurely ran out. During last month's servicing mission, astronauts hooked NICMOS up to an experimental refrigerator, which has now succeeded in chilling the instrument's detectors to their operating temperature of –203°C (–333°F). Such cold is necessary to avoid drowning out feeble infrared signals from space with thermal emissions from NICMOS itself.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.