NASA’s Juno flew by Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest satellite and the biggest moon in the solar system, on June 7, 2021.

Updates:

July 14, 2021: NASA has released an epic video of Juno's recent flyby past Ganymede and then, a day later, Jupiter. It is well worth a watch!

Note: this animation contains real images as well as modifications for a better video. For both worlds, JunoCam images were orthographically projected onto a digital sphere, and synthetic frames were added between actual images to make the motion appear smoother and provide views of approach and departure for both Ganymede and Jupiter. Read more in NASA's press release.

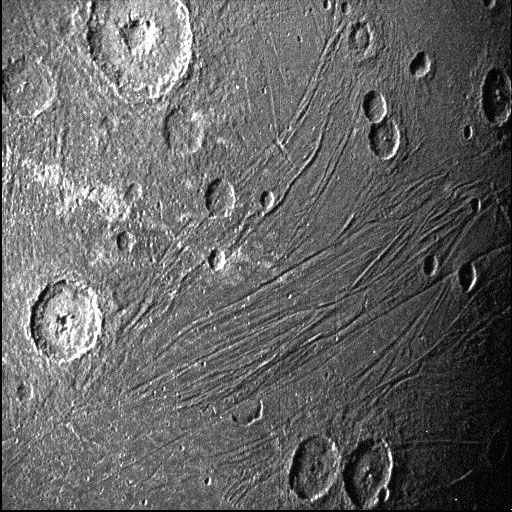

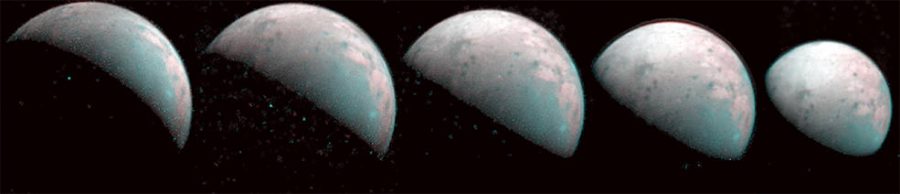

June 8, 2021: NASA has just posted new images from Juno's flyby showing the striated and cratered surface of the ice-covered moon:

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI

Read and see more in NASA's press release, and see additional images as they come in in the JunoCam archive.

On June 7th, NASA’s Jupiter-orbiting Juno spacecraft will perform a close flyby of Ganymede, passing about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) from the icy moon’s surface. This flyby places the mission alongside seven other planetary spacecraft that have photographed the moon over the last few decades, increasing our understanding of this unique world.

Part of the purpose of the flyby is to begin adjusting Juno’s orbit in anticipation of its extended mission, announced last January. But the flyby will also allow Juno to study some of Jupiter’s large moons from close range, and Ganymede is up first. This icy world is the largest moon in the solar system, bigger even than the planet Mercury, with a tenuous atmosphere and, unique among moons, its own magnetic field. It also probably has a subsurface ocean, though it’s not as accessible as the one on Jupiter’s Europa or Saturn’s Enceladus.

Photography was never intended to be a prime objective of the Juno mission, which focuses instead on measuring Jupiter’s magnetic fields, gravity, and atmosphere. But Juno nevertheless carries a public-outreach camera called JunoCam, which has been highly successful. It has provided rich imagery of Jupiter’s cloud tops and occasional distant views of the Galilean satellites, all downlinked as raw pictures that amateurs then processed into beautiful panoramas.

Now, JunoCam will have a chance to provide more detailed images of Ganymede. Before the new images arrive, let’s take a look at the history of Ganymede’s exploration up to this point.

17th Century: Discovery

The incomparable Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei discovered Ganymede — along with Io, Europa, and Callisto — in 1610. A series of winter evenings found Galileo aiming one of the world’s first telescopes at Jupiter, discovering three, and later four small dots near the planet. Galileo was initially intrigued because these “stars,” as he originally called them in his notes, were in a straight line near Jupiter’s equator. Within a few weeks, punctuated by the occasional cloudy nights (some things never change!), the truth became obvious: These celestial bodies were orbiting the larger planet.

1610–1973: Earth-based Observations

Unlike Jupiter, the moons were too far away for surface details to be resolved even in large telescopes. At best, observers could make some very slight albedo and color measurements. So what could possibly be learned about Ganymede and its companions when they appeared as nothing more than points of light, moving from night to night around the giant planet?

By examining Ganymede’s orbit, it was possible to approximate its mass and density, by which astronomers could in turn infer information about the moon’s composition. Spectroscopy also provided clues.

But sometimes those clues were misleading. An astronomy textbook from 1901, for example, comments on the low densities of the Galilean satellites: “It has been surmised that these satellites are not solid bodies, like the earth and moon, but only shoals of rock and stone, loosely piled together and kept from packing into a solid mass by the action of Jupiter in raising tides within them.” Ice or interior oceans, both of which also reduce the bulk density, weren’t yet considered.

In the end, even careful observations could only go so far. There were still no clues to the nature of Ganymede’s geography and surface details — was it a cratered world? Did it have maria like the Moon? Or something new entirely? The same 1901 textbook laments that while “each of these satellites may fairly be considered a world in itself, their great distance from us makes it impossible . . . to see more upon their surfaces than occasional vague markings, which hardly suffice to show the rotations of the satellites upon their axes.”

1973: Pioneer 10 and 11

That all changed with the space age. In 1973, the unmanned Pioneer 10 spacecraft returned the first images of Ganymede. The best of these photos showed Ganymede’s major surface geography for the first time, including details as small as 400 km across. The images were a little fuzzy and of fairly low resolution but far better than what had been achieved previously. Pioneer 11 also returned some images of Ganymede in 1974. Together, the spacecraft refined measurements of Ganymede’s mass and composition.

NASA

1979: Voyager 1 and 2

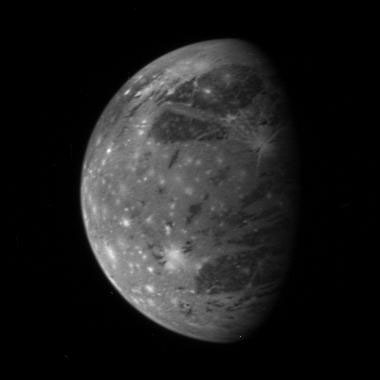

A real breakthrough came in 1979, when the twin Voyager spacecraft made close flybys of Ganymede. No longer seen as a point of light or a fuzzy disk, the photos from the Voyager probes show Ganymede as a dramatic world in its own right.

NASA / JPL

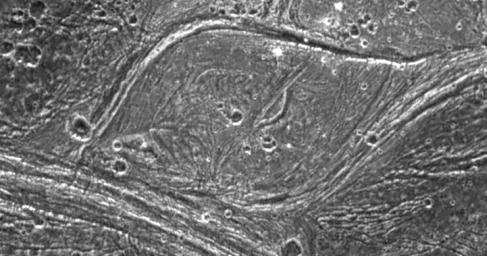

Mapping much of the moon’s surface, the Voyagers returned detailed images of Ganymede, showing that the dark regions were heavily cratered and that the lighter topography had been reworked by tectonic activity. The nature of the surface — a combination of ice and rock littered with cracks and craters — became clear at last. The probes also saw that Ganymede has polar ice caps. Earth from space is often called the “blue marble;” from close range, Ganymede appears as something of a “gray marble.”

NASA / JPL

1996: Galileo

The highly successful, although somewhat malfunction-plagued Galileo probe reached Jovian orbit in 1995 and performed six flybys of Ganymede over the next few years. It obtained even closer views of the moon than the Voyagers had: During one flyby, it passed a mere 225 km above Ganymede’s icy surface — flying more than 50 times closer than Voyager 2.

NASA / JPL

Galileo’s photos showed plains, mountains, and valleys, and some regions of rugged terrain disrupted by tectonic action. The probe also discovered that Ganymede has a magnetic field — the only moon in the solar system with that distinction. Much of our current understanding of Ganymede comes from this mission.

NASA / JPL / Brown University

2001: Cassini

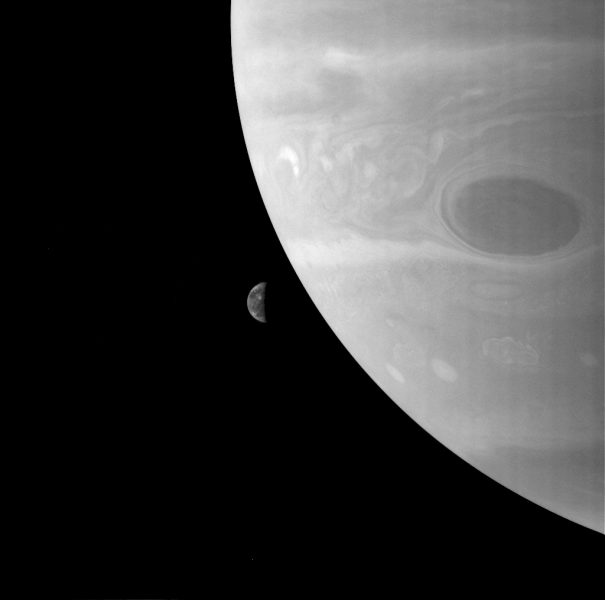

The fabulous Cassini spacecraft passed by Jupiter on its way to Saturn in 2001. Although it didn’t travel as close to Ganymede as other probes before it, Cassini did snap a handful of aesthetically appealing photos of the large moon juxtaposed against Jupiter’s turbulent cloudtops.

PDS / OPUS

2007: New Horizons

While en route to Pluto, New Horizons took advantage of Jupiter’s strong gravitational field to boost its trajectory; at the same time, the probe captured some excellent photos of the Jovian system, included a few distant images of Ganymede. Infrared spectral images filled in large gaps on compositional maps of Ganymede’s surface.

NASA / JHUAPL / SWRI

2016–present: Juno

And that brings us to Juno, NASA’s current mission at Jupiter. Even though exploration of the Jovian moons was not a primary focus of the mission, Juno has repeatedly photographed Ganymede, Europa, and Io, albeit from considerable range. The JunoCam has even given us our first views of Ganymede’s north polar region, thanks to Juno’s unique orbit around Jupiter.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / ASI / INAF / JIRAM

In addition to visual data, spectra taken during a 2019 Juno flyby enabled astronomers to map the distribution of water ice in Ganymede’s north polar regions and revealed the potential presence of magnesium salts, ammonia, and carbon dioxide on the surface. This region is inaccessible from Earth-based observations, so Juno’s explorations are valuable to scientists.

June 7, 2021: Juno’s First Close Flyby

Now, with Juno fast approaching Ganymede for another close-range study of the moon, new images and spectra will help further our understanding of this fascinating world. Once again, anyone with an interest is invited to “ride along” with the probe and view Ganymede from the perspective of a planetary spacecraft as data is downlinked. What will we see this time in the new photographs? What new sights await? Stay tuned to find out!

3

3

Comments

[email protected]

July 16, 2021 at 10:31 pm

In watching the video of Ganymede there were flashing dots of white occurring during the fly by. Any explanation for the flashes?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Michael Brough

July 19, 2021 at 3:32 pm

I thought they might be lightning flashes.But I am only guessing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

GerryH

August 12, 2021 at 9:20 am

Sunlight reflecting off ammonia ice clouds?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.