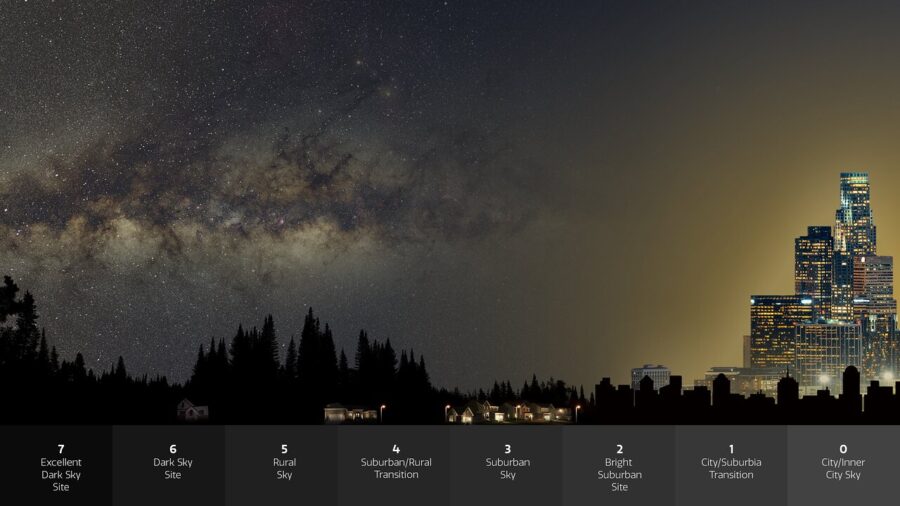

The average brightness of the night sky is increasing 10% every year, making the stars less visible.

NOIRLab / NSF / AURA, P. Marenfeld

How many stars can you see at night from where you live? According to results from a new study appearing this week in Science, the number is likely less than it was just a few years ago.

To arrive at that conclusion, Christopher Kyba (Ruhr University Bochum, Germany) and his collaborators analyzed data from the Globe At Night citizen-science project. The researchers found that the brightness of the night sky increased on average by about 10% every year between 2011 and 2022.

Skyglow is familiar to most amateur astronomers as the wash of light across the night sky, mostly from artificial light sources on the ground. It reduces the contrast between astronomical objects and the sky, making some observations difficult, if not impossible. The effect is greatest in and near cities.

Researchers have found that the nighttime light that yields skyglow also has important effects on the ground. Artificial light at night can negatively impact wildlife, energy security, and public safety. As a result, light pollution is increasingly considered an important environmental problem.

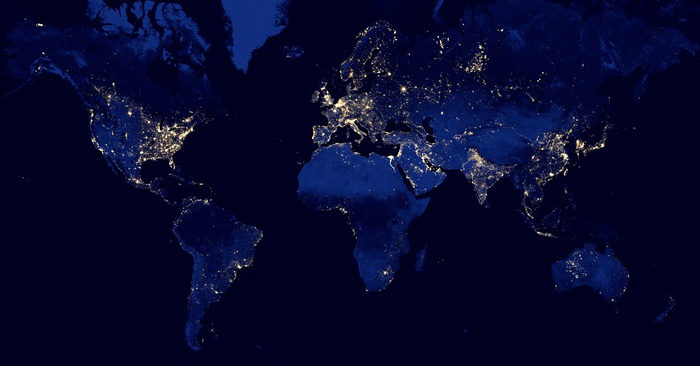

Until now, our best global view of light pollution came from satellite measurements of the Earth at night. They indicated that the amount of light emitted on the ground grew at an average rate of 2% per year between 2012 and 2016. But the new result from citizen scientists on the ground hint that satellites have underestimated the increase in a big way.

NASA

The new estimate differs from earlier results in part because the instruments aboard the current generation of satellites are effectively blind to blue light. In the past decade, governments in many parts of the world rushed to adopt white light–emitting diode (LED) technology. LEDs emit much more in the blue part of the spectrum than earlier light sources did, and that light scatters more efficiently in the atmosphere than other colors. Also, because LEDs use much less energy than earlier light sources did, regions tend to install more (and brighter) fixtures, which may negate the cost savings. But even as observers on the ground generally saw their night skies brighten from the transition to brighter, bluer LEDs, satellites missed much of the change.

Furthermore, satellite sensors don't see light emitted toward the horizon from sources like windows and illuminated signs very well. That light is an important contributor to what observers perceive as skyglow. And particularly in the early evening hours, these sources may be the dominant source of skyglow near cities.

Visual observations like those collected by Globe at Night can account for at least some of the “missing” light. By counting the number of visible stars in the night sky, citizen scientists include the influences of both increasing light emissions and the shift toward generally bluer light sources.

Salvador Bará, a light pollution researcher formerly of the University Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain, who was not involved in the study, says this approach was crucial to the outcome of the investigation.

“This work reports on the real vision of the night sky with the naked eye, without relying on technological instruments,” Bará said. He added that it “underscores the power of citizen science to assess changes in our environment on a global scale.”

Globe at Night participants contributed over 50,000 individual observations during the study period. Many came from parts of the world where deploying ground-based light sensors was impractical or even impossible.

Yet even that mountain of data could sample night-sky conditions only on large scales. “We were only able to look at continental trends, because we don't have sufficient data to look at smaller regions,” Kyba explains.

More program participants would improve the results, Kyba suggests. It's also important to recruit volunteer observers in parts of the world underrepresented in past Globe at Night campaigns. Satellite data suggest that’s where light pollution and skyglow may actually be growing the fastest.

Despite high confidence in certain approaches known to reduce light pollution, the researchers concluded that current efforts don't seem to be working. And failure to cut back on wasted outdoor light at night can have real impacts on communities. The main messages of light pollution reduction might be better conveyed to governments if the study results were more targeted to specific geographies.

Raising the number of Globe at Night observations each year by a factor of 10 would make it possible for researchers to look at trends on much smaller scales than they can now. “If we could do that, we would surely find places that are doing better than average,” Kyba says, “and we could try to figure out what they are doing right.”

Kyba argues that this is why the conclusions of the paper affect everyone — not just astronomers. “Even if you don't care about the stars, this result should matter to you,” he said. “It's a visual representation of your community's waste of money and energy as a result of poor lighting design or installation.”

You can join Globe at Night — find instructions here.

6

6

Comments

Mike McCabe

January 22, 2023 at 5:05 pm

The culprit is the LED revolution. Ultra-bright, cheap to purchase, economical to run, people who don't understand light pollution (which is most people) are gravitating to them like moths to, well, lights. They're loving the bright-as-daytime illumination on their properties at night, regardless of whether they need that much illumination or not. I don't see any good way out of the situation. When we talk to folks about light pollution as an issue we're just brushed off like some societal anomaly. People come back from vacation trips to places where it's darker and even if they notice they don't consider any effort to remediate their own local situation. To them it's just the way it is. Sorry to be so gloomy on the topic, but I just see a general lack of appreciation for the effects of light pollution and the only real solution for those of us that really want darker skies is to move away from populated areas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

January 23, 2023 at 6:15 pm

It is easy to get discouraged. I don't think that moving away from populated areas is an effective long-term solution. What are you going to do when somebody moves in down the road and put in yard blaster lights?

We can't solve this problem on an individual basis. Many communities around the world recognize the problems caused by light pollution and have started using good outdoor lighting practices. Check out the International Dark Sky Association for encouraging news and tips for how to get involved.

https://www.darksky.org/category/dark-sky-places/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dom

January 25, 2023 at 5:12 pm

I couldn't put it in a better way Mike. Agree very much with the words "societal anomaly". I live in Belgium (region Flanders), the very bright spot east of England in the composite image above. The every year grewing fewer times i make an effort to take out one of my telescopes ends in a feeling of disillusion. So i turned recently to solar observing. But that doesn't make me feel any better about the fact that we can't enjoy the wonders of the night sky any more. The situation in Belgium has always been very bad, already from the time i started stargazing (40+ years ago now). Despite the good efforts of organisations like IDSA and the local association who try to raise awareness of the negative effects of light pollution, it is a fact that most people won't give up their security feeling of well illuminated roads, private properties, etc. I pass much of my yearly holidays in the Alps (Austria mostly). There, high in the mountains, the sky is still dark. Sometimes so dark i can't even recognize some of the constellations, being used to my poor skyconditions. But to go even for a two or three day observing session that far (about 1.000 k), no thanks. I have some spots with better observing circumstances at about 150 k but you will agree that after a day's work it's not that easy to load all your gear in the car and drive off. Perhaps to find cloudcovered skies when you arrive at the spot.

I always like the comments from Anthony. Always very positive despite the fact that he is observing from SF, i think even worse skies than over here.

Perhaps i am also too gloomy, but the situation is what it is, not good in this case.

One last remark : being interested in meteor observing i read sometimes reports of meteor observers here in Belgium. What i find most intriguing is that they most of the times reach limiting magnitudes around 6.5 - 6.7 in a (bright) suburban sky. My vision (certainly with my glasses on) is not bad. I wonder how they do it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tony Flanders

January 22, 2023 at 8:33 pm

I suspect that the rather dramatic decrease in reported NELM is due primarily to increased glare -- lights shining directly into the observers' eyes -- rather than increased skyglow. In many discussions with beginning and prospective backyard astronomers. it appears that the biggest problem is their next-door neighbor's security light, not the light of the sky itself. This would explain the discrepancy between the satellite observations and Globe at Night's conclusions, because local glare is generally caused by low-wattage sources that would be undetectable by satellites, and would have negligible effect on skyglow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

January 23, 2023 at 3:36 pm

This is my situation. I observe from my back yard in San Francisco. No street lights shine directly into the yard. When all the neighbors' lights are off, I can see third magnitude stars naked eye, even fourth magnitude when the sky is very clear. If even one outside light is on from one of the eleven surrounding households, I might not be able to see second magnitude stars. I've talked to all my neighbors and they mostly remember to turn off their outside lights when they're not using them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John

January 23, 2023 at 11:32 am

I've noticed it as well. I can do no RGB imaging any longer and even narrowband has become iffy, mostly due to transparency in north east Ohio. Planetary and solar imaging is still OK but not much else.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.