Technology may have revealed a piece of the long-lost works of Greek astronomer Hipparchus, one of the greatest astronomers of antiquity.

Peter Malik

Sometime between 162 and 127 BC, the great Greek astronomer Hipparchus drew up the first star catalog of the western world, containing descriptions and coordinates of some 850 stars in the northern sky.

At least, that’s what later sources say — copies of Hipparchus’s list have never been found. Until now, that is. Writing in the Journal of the History of Astronomy, three European scientists claim to have uncovered a small part of the long-lost catalog. “I felt nothing short of awe when I first heard about it,” says astronomy historian and writer William Sheehan.

In the 2nd century AD, Claudius Ptolemy compiled a catalog of 1,025 stars in 48 constellations to include in his magnum opus, Almagest. Ptolemy also hinted at the existence of an earlier listing, some scholars have suggested that Ptolemy’s work was based not on his own observations but on Hipparchus’s catalog.

Hipparchus was born around 190 BC in Nicaea, in what is now northwestern Turkey, but he carried out most of his astronomical work on the island of Rhodes. He made the first estimates of the distances and sizes of the Moon and the Sun, and was the first to discover precession: the slow wobble in the orientation of the Earth’s spin axis. According to astronomy historian Bradley Schaefer (Louisiana State University), Hipparchus was “arguably the best and greatest astronomer in the world before Copernicus.”

“Only one of his many books, The Commentaries, has survived,” says Schaefer, “with the most important loss being his influential star catalog.”

That’s why scientists are elated about the new find. “It […] illuminates a crucial moment in the birth of science, when astronomers shifted from simply describing the patterns they saw in the sky to measuring and predicting them,” astronomy historian James Evans (University of Puget Sound) told Nature.

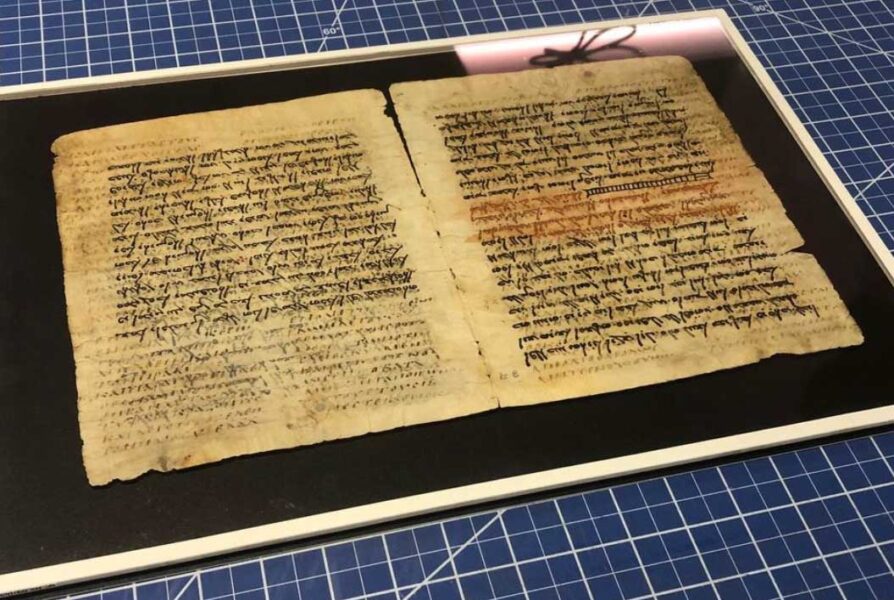

Peter Williams (Tyndale House, UK) and Victor Gysembergh and Emmanuel Zingg (Sorbonne University, France) studied the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a 9th- or 10th-century manuscript from the Saint Catherine’s Monastery on the Sinai peninsula in Egypt. The codex, which is now kept at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., contains Christian texts in Syriac.

Museum of the Bible 2021 / Journal for the History of Astronomy 2022

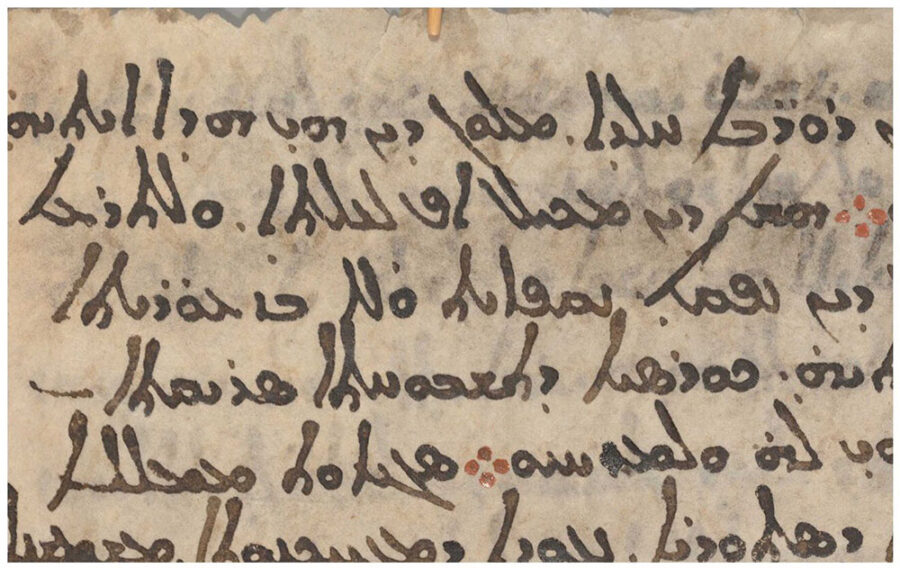

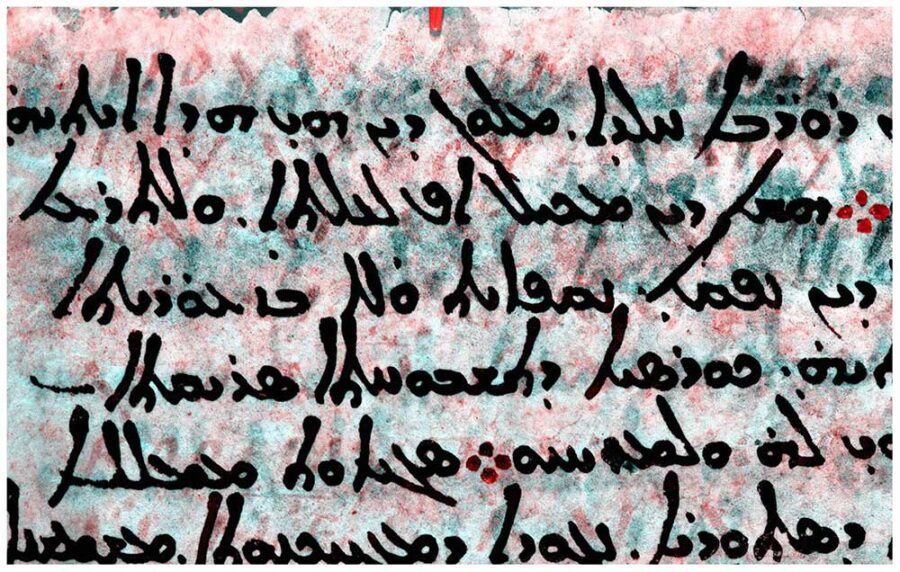

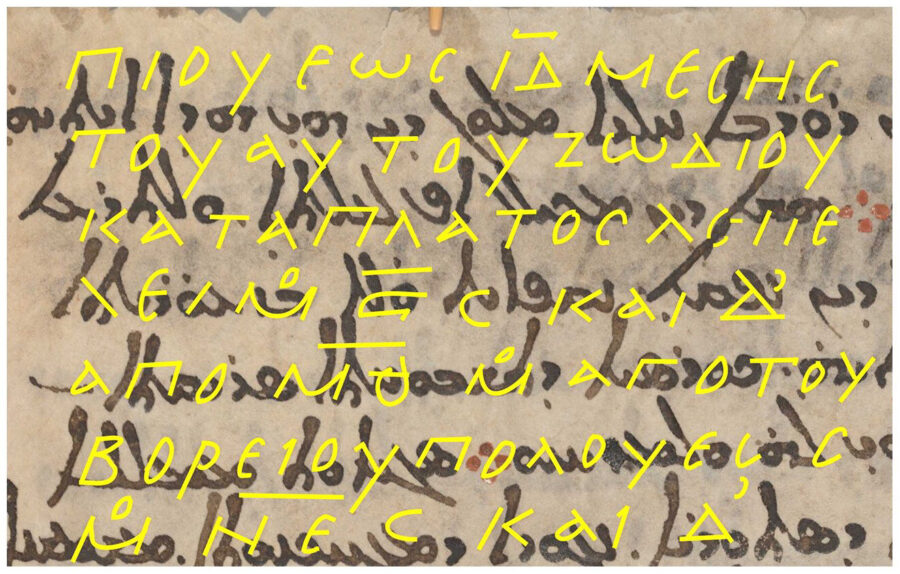

Beneath the visible text on one of the folios is a so-called palimpsest — the almost indiscernible imprint of an older text that medieval copyists had scraped off in order to re-use the costly parchment. By meticulously studying dozens of images made at various ultraviolet wavelengths, the scientists revealed the older text, which probably dates from the 5th or 6th century A.D.

Museum of the Bible 2021 / Journal for the History of Astronomy 2022

Museum of the Bible 2021 / Journal for the History of Astronomy 2022

The Greek palimpsest text describes the constellation Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown, providing information on its extent on the sky and on the coordinates of four of its stars (now labeled α, β, δ, and ι). These coordinates neatly agree with the stellar positions around the time Hipparchus drew up his catalog.

“The ‘style’ and coordinate system of the brief text in the palimpsest is similar to that used by Hipparchus in The Commentaries,” says Schaefer, “so the palimpsest might plausibly have a Hipparchan heritage.” However, he warns that this is “far from proven.” Still, most scientists appear to be convinced that part of the oldest star catalog in history has finally come to light. “It is one of the most thrilling things to happen in astronomy history for a while,” says Sheehan. “What else remains out there to be found out from one of the ancient palimpsests?”

The discovery shows that Hipparchus used equatorial coordinates, and that his measurements were accurate to within one degree. In contrast, Ptolemy’s catalog, compiled almost three centuries later, used ecliptic coordinates and was significantly less accurate. According to Williams, Gysembergh and Zingg, this implies that Ptolemy’s work was not based solely on data from Hipparchus.

“It’s a remarkable discovery,” says Sheehan. “It will force us to completely rethink our views about the ancient world, and in particular it shows that the cycles of discovery and science do not, as we like to think, follow a progressive line forward, and that even Ptolemy’s work represents something of a dark age compared to some of his predecessors.”

5

5

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

October 22, 2022 at 10:27 pm

A tiny quibble: Hipparchus didn't discover that the Earth's spin axis was wobbling. he discovered that the celestial sphere was very gradually speeding up in it's rotation around the unmoving Earth. It would take a couple of millennia for people to figure out that the Earth was rotating.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

PGT

October 23, 2022 at 7:20 pm

what would that observation look like?

how would one perceive that in the span of a human lifetime?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 23, 2022 at 9:39 pm

Hipparchus compared his observations with those made by earlier astronomers. Here is more detail from http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/glossary/hipparchus

"This notable discovery was the result of painstaking observations worked upon by an acute mind. Hipparchus observed the positions of the stars and then compared his results with those of Timocharis of Alexandria about 150 years earlier and with even earlier observations made in Babylonia.

"He discovered that the celestial longitudes were different and that this difference was of a magnitude exceeding that attributable to errors of observation. He therefore proposed precession to account for the size of the difference and he gave a value of 45" or 46" (seconds of arc) for the annual changes. This is very close to the figure of 50.26" accepted today and is a value much superior to the 36" that Ptolemy obtained.

"The discovery of precession enabled Hipparchus to obtain more nearly correct values for the tropical year (the period of the Sun's apparent revolution from an equinox to the same equinox again), and also for the sidereal year (the period of the Sun's apparent revolution from a fixed star to the same fixed star). Again he was extremely accurate, so that his value for the tropical year was too great by only 6 1/2 minutes."

You must be logged in to post a comment.

PGT

October 23, 2022 at 11:41 pm

Thank you!

This kind of informed response is what makes this a great online site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

wadecaves

November 9, 2022 at 6:20 pm

A quibble about your quibble – in his Almagest, Ptolemy dismisses claims that the earth rotates on its axis, showing that this idea was not uncommon in intellectual circles even if it didn't dominate mainstay theory:

"But certain people,* [propounding] what they consider a more persuasive view, agree with the above, since they have no argument to bring against it, but think that there could be no evidence to oppose their view if, for instance, they supposed the heavens to remain motionless, and the earth to revolve from west to east about the same axis [as the heavens], making approximately one revolution each day; or if they made both heaven and earth move by any amount whatever, provided, as we said, it is about the same axis, and in such a way as to preserve the overtaking of one by the other. However, they do not realise that, although there is perhaps nothing in the celestial phenomena which would count against that hypothesis, at least from simpler considerations, nevertheless from what would occur here on earth and in the air, one can see that such a notion is quite ridiculous."

Ptolemy then goes on to say that those convinced of axial rotation have overlooked that the speed and force of the earth's daily rotation would overtake all motion on earth and force everything into east-to-west motion.

Ptolemy dismissed their theory because he thought he could do better with something simpler and more intuitive, and the weight of his reputation did contribute to low adoption in the centuries that followed him. But mathematicians love fringe folk; we have heliocentric tables of planetary positions centuries before heliocentric models became mainstream, and here too we have intellectual divergence – just a minority voice hard to find, but thankfully observable in passages of refutation by those writing a more majority opinion.

* In footnotes, translator G. J. Toomer cites Heraclides of Pontos (late fourth century BC) as the earliest known source for the idea of axial rotation – so this idea would have had over five centuries of development before Ptolemy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.