Capella is the sixth-brightest star in the sky — and it’s more than one star. The main two stars in the system are near-twins, bright yellow giants.

Vitals

| Official name | Capella |

| Other designations | Alpha Aurigae, HIP 24608, HD 34029 , HR 1708 |

| Nicknames | The Goat Star |

| Apparent magnitude | 0.08 |

| Distance from Earth | 42.8 light-years |

| Composite type | G3III |

| Color | Yellow |

| Mass of primary | ~2.7 M☉ |

| Radius of primary | ~12.2 R☉ |

| Constellation | Auriga |

| Right ascension | 05h 16m 41s |

| Declination | +45° 59' 52” |

| Multiple system? | Yes |

| Variable star? | No |

| Exoplanets status | None known |

| Probable fate | White dwarf / planetary nebula |

Capella's Physical Characteristics

Capella is one of the brightest stars in the sky and the crown jewel of Auriga, the Charioteer. Like many other stars, Capella appears to be a single object but is actually a multi-star system. The primary members are two yellow giant stars, designated Capella Aa and Ab. They orbit about a common center of gravity, separated by only about 0.72 astronomical units, where an a.u. is the distance from Earth to the Sun.

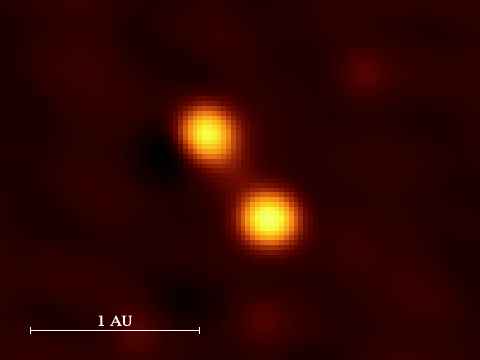

The two stars' mutual orbit is angled 137° relative to the plane of the solar system, so we get an almost face-on view. Because we see the system at such a large angle, the two Capellas don’t eclipse each other from our perspective. The two stars are so close, they can’t be split visually with ordinary equipment and are only just resolvable with the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST), so don’t be disappointed when your telescope only reveals a single yellowish-white point.

COAST / University of Cambridge, UK

Besides the double yellow giants, the Capella system also boasts a pair of red dwarf stars, apparently gravitationally bound to the others but separated by a tremendous distance of more than 1,000 a.u. (For a sense of scale, Voyager 1, our most distant space probe, has traveled only 150 a.u.) The red dwarfs are roughly half the Sun’s mass and shine with less than 2% of its luminosity.

Origin / Mythology

The oldest myths concerning Capella are Mesopotamian and associate Capella with a goat. In fact, the modern Capella is derived from the Latin word “capra,” meaning “goat,” which can refer to a “she-goat” or “little goat.” Nearby is a small acute triangle of stars playfully known as “The Kids,” presumably the offspring of Capella the Goat. It’s no surprise that goats should find their way into the ancient sky, as they are among the oldest domesticated animals. It doesn’t take much imagination to visualize a goatherd watching their animals on a cold evening as Capella rises in the north.

Daniel Johnson

Capella’s constellation is Auriga, the Charioteer. It represents one of several possible Greek myths involving various chariot drivers, including the mythological inventor of the four-horse chariot. These stories are definitely younger than the goat associations.

Interestingly, there seems to have been a conflict between the strong caprine associations with Capella and the late chariot myths. As a result, you might see Auriga represented artistically as a chariot driver holding a goat — even though there are really no surviving myths combining the two. (Sometimes the Kids are represented, too). This is not unlike visualizations that depict Lyra as an eagle grasping a harp; trying to merge two otherwise unrelated legends.

How to See Capella

Capella is an excellent autumn and winter star. In early autumn it can be found at dusk just coming up over the north-east horizon, before pivoting around Polaris for the next few hours and gaining impressive height overhead in the sky. When it’s low on the horizon, Capella often displays rapid blinking and color shifts similar to Sirius, caused by the light of a relatively bright object passing through Earth’s atmosphere.

By January, the star is already far overhead in the evenings; if you’re far enough north, it can be nearly at the zenith. At about zeroth magnitude, it ranks as the sixth-brightest star in the night sky.

Daniel Johnson

Many skywatchers are familiar with the Big Dipper’s “pointer” stars—Dubhe and Merak—that can be used to locate Polaris. Similarly, you can a variation of this idea by using Dubhe and Megrez to point to Capella. The distance you must sweep to Capella is farther than to Polaris, but since there aren’t any comparably bright stars between Dubhe and Capella it’s a pretty obvious jump.

It can be interesting to watch Capella rise in the northeast and continue east for a time before pirouetting back to the northwest — unlike the Sun, Moon, and outer planets that take arcs from east to west across the entire sky. Why not give it a try tonight?

Daniel Johnson is a Wisconsin-based freelance writer and professional photographer and the co-author of over a dozen books. He’s a longtime amateur astronomer and fortunate enough to live in a rural region with excellent seeing conditions. You can view some of Dan’s photography (he does a lot of animals!) at www.foxhillphoto.com

2

2

Comments

Yaron Sheffer

November 29, 2020 at 11:03 am

"Interestingly, the two stars’ orbits are parallel to the plane of the solar system" is a perplexing statemet. Any supporting evidence? Unless you mean parallel to the plane of the sky?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Monica Young

December 1, 2020 at 9:43 am

I've clarified this statement in the text.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.