It's been nearly six months since the Messenger spacecraft began orbiting Mercury. In that time the innermost planet has circled the Sun twice and twirled around three times — long enough for NASA's robotic emissary to get a really good look at the entire globe at close range.

Not surprisingly, then, a tidal wave of new results have come from the eight instruments aboard, and much of Science magazine's September 30th issue showcases all that's new with the innermost planet. I can't do justice to each investigation here, so I hope the science team will forgive me for focusing on the compositional findings — from which a remarkable story is emerging.

You'll recall that, as of mid-June, it was already becoming clear that Mercury's surface is unlike that of its planetary siblings near the Sun. Its exterior bears only slight geochemical resemblance to the outer layer of Mars and to the seafloor crust on Earth and none at all to the Moon's low-density, metal-poor crust. Instead, the combination of a high magnesium-to-silicon ratio and an abundance of the "volatile" rock-forming elements sodium, potassium, and sulfur make Mercury unique among the terrestrial worlds.

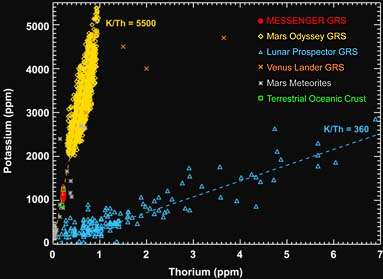

The abundance of potassium (K) and thorium (Th) on the surface of Mercury, as measured by the Messenger's gamma-ray spectrometer, compared to the abundances for Venus, Earth, Moon, and Mars. The K/Th ratio is a sensitive measure of high-temperature processes during a planet's evolution. Click on the image for a larger version.

P. Peplowski & others / Science

Of special interest to geochemists are the abundances of naturally radioactive isotopes in the crust — specifically potassium (K), thorium (Th), and uranium (U) — which give off gamma rays that the spacecraft detects as it swoops overhead. According to Patrick Peplowski (Applied Physics Laboratory), who heads the team analyzing results from Messenger's gamma-ray spectrometer, the ratio of potassium to thorium in Mercury's surface rocks is some 15 times that of the Moon. Likewise, the X-ray spectrometer has found at least 10 times more sulfur than occurs in the silicate rocks of either the Earth or Moon. Yet, what's remarkable for a planet whose metallic core takes up more than three-fourths of its diameter and half its volume, the surface rock contain very little iron.

Ever since Mercury was first visited by a spacecraft, back in the 1970s, scientists have wondered how this cannonball-hearted planet came to be. Finally, after nearly four decades of collective head-scratching, Messenger's compositional results are starting to reveal what really happened — or at least what didn't happen — when Mercury came together 4½ billion years ago.

Did Mercury come together from countless protoplanets enriched in elements like iron, sulfur, and potassium, as dramatized here — or did its formation involve a violent, chemistry-altering event?

Julian Baum / Take 27 / Nature

"The exciting thing about our observation of volatiles on the surface of Mercury is that it rules out most theories for the planet's formation," Peplowski explained during a press briefing on Thursday.

For example, in order to end up with such a plus-size core, some researchers had speculated either that the planet's outer layers were vaporized by an early bout of intense sunlight or that its crust ended up in smithereens after one or more giant impacts. But either of these scenarios would have left young Mercury boiling hot, driving away virtually all of the easy-to-vaporize elements that Messenger now finds so abundantly.

Instead, cosmic chemists are now thinking that Mercury didn't suffer some bizarre accident in its infancy but instead formed from planetary building blocks rich in volatile elements and metals like iron and magnesium. It all seems to fit (particularly highly diagnostic K/Th and Th/U ratios) if the planet had accumulated from a little-known type of meteorite known as enstatite chondrites. Gather enough of these in one place, then heat them until all the iron sinks to form a core, and you'd be left with a surface layer much like what the spacecraft is finding.

This story is holding up for now, but we've yet to hear from one of key Messenger team: the dynamicists who are using spacecraft tracking data to deduce how mass is distributed inside the planet. I hope those results emerge soon — but in the meantime I'll sit back and enjoy all the wild and wonderful views that Messenger beaming back to Earth daily.

6

6

Comments

Chandler Kennedy

October 4, 2011 at 7:09 am

A possible low-temperature method for stripping Mercury's mantle to make the relatively large core is a tidal close encounter with a larger planet. See numerical results of such an encounter in Asphaug, et. al. Nature V439 p155 (2006). A giant impact is not the sole mechanism capable of mantle stripping.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Geoff Bell

October 8, 2011 at 4:51 am

Your usage of these flashing images seems to be increasing. The one below from Meade Instruments is a minor irritation as it is at the bottom of the page. Your one next to the picture of Mercury makes the article unreadable unless I cover it with my hand. Please be more careful in your usage of moving images.

Thank you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

October 8, 2011 at 9:30 am

The science used to explain Mercury's origin I find suspect. Consider the current exoplanet count is now at 692 (http://exoplanet.eu/index.php). 300 of these bodies orbit <= 0.4 AU from their host star like Mercury or closer. The average mass of this population is 1.33 Mjup. Average host star mass is 0.99 Msun and average effective temp is 5544 K. What we should see given such exoplanet data is planets similar to Jupiter or larger moving around our Sun where Mercury is today. Attempting to explain such differences illustrates the speculative nature of planetary science.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

eanassir

October 9, 2011 at 1:32 pm

The origin of Mercury

It together with the rest of the planets of our solar system, including the Earth: all the planets were one sun which cooled down then burst to form nine pieces and the nearest sun attracted these pieces to be the present Earth and the rest of the planets, and the new sun that attracted them is our present Sun.

http://www.quran-ayat.com/universe/index.htm#Formation_of_the_Planets_

Therefore, the constituents of Mercury and the other planets are almost similar, with some maybe minor differences.

Mercury became cold and lost its internal heat; so it lost its gravity and it stopped spinning around itself, and now faces the Sun with one face only which is very hot; the other side is the dark side with extreme coldness.

The craters are due to the falling of a large number of comets attracted to this cold object.

The scarps and the torps are due to the contraction of Mercury after becoming cold.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

eanassir

October 9, 2011 at 1:43 pm

Mercury is doomed, following its cessation from axial spinning around itself.

One side is the day side facing the sun: perpetual day in which very high temperatures resulted, and life was exterminated on Mercury long time ago.

The atmosphere gases mixed with each other forming a thick smoke (like the situation now on Venus), then the atmosphere was lost into the outer space, and now Mercury is almost without atmosphere or very thin one.

Rivers and seas evaporated.

Rocks of mountains have been smashed by the heat of the sun.

Comets fell down heavily in large number leading to the craters.

http://www.quran-ayat.com/universe/new_page_4.htm#The_Burnt_World

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Simon Hanmer

October 18, 2011 at 5:33 pm

Kelly ...

Excellent, clear summary of the latest surface chemistry results. NASA was a very long time in releasing these. Enstatite chondrites are tempting, but it begs the Q as to why they would have been focused in the inner Solar System. It'll be interesting to see what the planetologists come up with on this one.

Thanks for your clarity ...

Simon (professional geologist with a major geological survey)

PS : when do you get your honorary geology degree? ... or do you already have a geo-background?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.