During the 2004 Geminid meteor shower, Alan Dyer caught a bright fireball with a tripod-mounted digital camera. He used a wide-field, 16-mm lens for a 1-minute exposure at f/2.8 with an ISO setting of 800. Expect to shoot a lot of frames before you get this lucky.

Alan Dyer

No matter what your level of interest in astronomy, everyone seems to enjoy the brief and sometimes dazzling streaks of light from meteors, sometimes called "shooting stars." These can occur at any time on any night. On most nights a half dozen of these sporadic (random) meteors appear hourly.

However, several times each year Earth encounters a stream of debris left by a passing comet, and the result is a meteor shower. You'll notice the difference if you watch the sky for a half hour or so: not only do the number of meteors you'll see go up, but also the meteors seem to fly away from a common point in the sky called the radiant.

A shower gets its name from the constellation where this radiant lies — for example, August's well-known Perseid shower has its radiant in Perseus. One notable exception to this rule is the Quadrantid shower, named for the now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis. Instead, its radiant lies in the constellation Boötes. In any case, the higher a shower’s radiant, the more meteors it produces all over the sky.

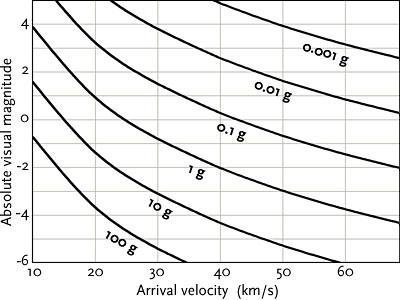

A meteor's brightness, plotted here as it would appear directly overhead at an altitude of 60 miles, depends on its mass and the speed at which it enters the atmosphere. Particles typically range in size from sand grains (upper right) to walnuts (lower left).

M. Campbell-Brown / P. Brown

Meteor showers peak during the predawn hours on the dates listed below, though they're typically active a few nights before and after the peak date. Note that the rates are for ideal conditions: very dark skies free of moonlight or light pollution; most likely you'll see somewhat lower rates than those listed. Following the table are specific predictions for each shower's prospects during 2012.

For the best possible viewing experience, find a dark location, make yourself comfortable in a reclining chair, and wear plenty of warm clothing. And for more information on watching and studying meteors, see Meteors: A Primer and the other articles in the Meteor section of our website.

| Major Meteor Showers in 2012 | ||||

| Shower | Radiant and direction | Morning of maximum | Hourly rate | Parent |

| Quadrantid | Draco (NE) | Jan. 4 | 60-120 | 2003 EH1 |

| Lyrid | Lyra (E) | Apr. 22 | 10-20 | Thatcher (1861 I) |

| Eta Aquarid* | Aquarius (E) | May 5 | 20-40 | 1P/Halley |

| Boötid | Boötes (NW) | June 27 | 10-40 | 7P/Pons-Winnecke |

| Delta Aquarid* | Aquarius (S) | July 28 | 20 | 96P/Machholz |

| Perseid | Perseus (NE) | Aug. 12 | 60-80 | 109P/Swift-Tuttle |

| Orionid | Orion (SE) | Oct. 21 | 10-20 | 1P/Halley |

| Leonid | Leo (E) | Nov. 17 | 10-20 | 55P/Tempel-Tuttle |

| Geminid | Gemini (S) | Dec. 14 | 100 | 3200 Phaethon |

* Moonlight will wash out fainter meteors in these showers.

January 4: The Quadrantids

Although a waxing gibbous Moon will be competition for this year's "Quads," it will set by about 3 a.m., providing a few dark hours for meteor watching before dawn. The peak for this short, sharp shower favors North Americans, especially in the eastern half, where viewers can expect to see 100 meteors per hour. Unlike most other showers, there's practically no activity on the days just before or after the Quadrantids' maximum. This shower's radiant is in northern Boötes, which rises in the northeast about 1 a.m. and climbs higher hour by hour.

April 22: The Lyrids

Although this isn't one of the year's strongest showers, the Moon is new when the Lyrids peak. Count on seeing roughly a dozen or so meteors per hour emanating from a radiant near the Hercules-Lyra border. As with the Quadrantids, this shower puts on a fairly brief performance — one that this year favors observers across North America, especially those on the East Coast.

May 5: The Eta Aquarids

This shower is spawned by none other than Halley's Comet. It's typically a good one for Northern and Southern Hemisphere observers, though the radiant, in the Water Jar of Aquarius, rises late for northerners. This year strong light from a full Moon will wash out most of them, so don't expect to see more than 20 or so per hour.

June 27: The Boötids

Ordinarily observers wouldn't expect much from either of the Boötid displays (there's another weak one in January). This shower's parent comet has an orbit outside Earth's that comes no closer than 0.24 astronomical unit, but some modest outbursts have been noted that were likely due to dust ejected during the 19th century. So you might catch one or two dozen Boötids per hour during this year's maximum. The waning crescent Moon won't be a problem, and the shower's radiant has a declination of +48° — placing it above the horizon almost all night for mid-northern observers.

July 28: The Delta Aquarids

Conversely, the Aquarid showers are best seen from the Southern Hemisphere because their radiant is below the celestial equator. Light from a waxing gibbous Moon will be a factor and probably wash out many of the predicted 20 or so Delta Aquarids per hour.

August 12: The Perseids

The Perseid shower is a popular display because it offers up to 60 an hour under a summer sky. Showtime usually begins as soon as the radiant (near the Double Cluster in Perseus) clears the horizon, an hour or so before midnight, and it climbs higher in the sky throughout the night. Unlike last year's display, which was spoiled by a full Moon, there'll be only a waning crescent hanging around during this year's maximum. The Perseids' parent comet is 109P/Swift-Tuttle.

October 21: The Orionids

This is another modest shower due to Halley's Comet. A waxing crescent Moon won't be a problem in 2012, so watch for 10 to 15 hourly meteors that stream from the shower’s radiant, located above Orion’s bright reddish star Betelgeuse.

November 17: The Leonids

Typically the Leonid shower is a weak display, with fewer than a dozen meteors per hour radiating from Leo’s Sickle. But the parent comet, 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, tends to create narrow concentrated streams that produced brief but prodigious displays in the late 1990s, when it last swung through perihelion. Since then the shower's activity has varied from year to year, but despite moonless skies the 2012 edition is unlikely to deliver much beyond its usual trickle.

December 14: The Geminids

With an average of 100 meteors per hour radiating from near the bright star Castor, this end-of-the-calendar shower is usually one of the year’s best. Each year the Geminids reach their maximum just four days later in the lunar cycle than the Perseids do. So, for this year's performance, the Moon will be new. Better still, you don't have to stay up until the wee hours to see them — at mid-northern latitudes, the radiant is well up in the sky by 9 p.m. Geminid meteors come from 3200 Phaethon, an asteroid discovered in 1983.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.