Looking down on Curiosity's landing site from on high, a high-resolution camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has spotted crash sites with several pieces of the spacecraft that accompanied the rover to the floor of Gale crater.

There was a time when Martian landers made their dramatic passage through the planet's thin atmosphere and onto its bleak surface completely in isolation. No one back on Earth would know the landing's outcome until the spacecraft "phoned home."

But no longer. When NASA's Phoenix descended toward its polar landing zone in May 2008, NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter was waiting overhead to capture the dramatic descent of the capsule and its parachute.

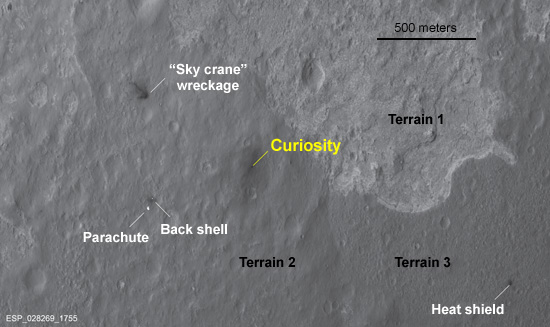

An image taken looking down from orbit on Curiosity's landing site reveals not only the spacecraft but also its parachute, both halves of the protective shell that surrounded it, and the rocket-powered "sky crane" that lowered it to the surface. Note the three distinct terrain types in the rover's vicinity. Click on the image for a larger version. NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona |

Likewise, when Curiosity dropped to the floor of Gale crater on August 6th, three craft in orbit around Mars were listening for its radio transmissions and once again MRO was waiting and ready to photograph its parachute-assisted descent.

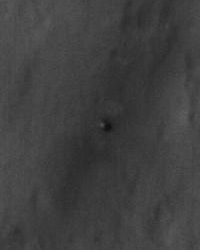

A bird's-eye view of Curiosity on the Martian surface, as imaged by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter a day after the rover landed. As the rover and its descent stage neared the surface, rocket thrusters blew away bright surface dust, exposing the darker material seen around the rover.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona

Now MRO has certified that Curiosity ended up where it's supposed to be — and spotted the wreckage of several pieces of the spacecraft that accompanied the rover to the floor of Gale crater. Taken just 24 hours after August 6th's landing, the scene above was recorded by MRO's ultrasharp HiRISE camera from a distance of about 210 miles (340 km). Even from so far away, HiRISE recorded details as small as 15 inches (39 cm) per pixel.

"It's like a crime-scene photo," notes Sarah Milkovich, HiRISE investigation scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Vague black smudges to the northeast and southwest of Curiosity show where rocket exhaust scoured away the surface's coating of bright dust. The parachute and back half of the descent capsule are sprawled across the ruddy surface some 2,020 feet (615 m) to the rover's southwest. The forward-facing heat shield, which fell away several miles up, lies nearly twice as far to the southeast.

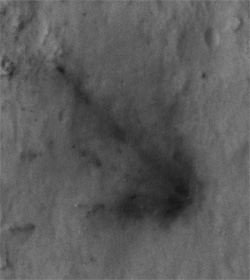

Some 2,100 feet (650 m) to the northwest is the rocket-equipped "sky crane" — or rather what's left of it. There's a big, dark splash, with rays extending away from the rover. The rocket assembly had been preprogrammed to fly itself some distance from the touchdown site after cutting itself loose from the rover, and Milkovich notes that the lopsided pattern is consistent with an oblique impact.

A close-up of the spot where Curiosity's rocket-powered "sky crane" crashed after distancing itself from the rover after landing. The spray of dark debris suggests that the platform struck the ground at an oblique angle.

NASA / JPL / Univ. of Arizona

As tempting as it might be to have Curiosity check out the piles of wreckage, that won't happen, says Michael Watkins, JPL's manager for the mission. The risk of the rover becoming contaminated (say, from leftover hydrazine in the rockets' fuel tanks) is too great.

Of more interest to the science team is the convergence of three very different terrains only a few hundred yards to the rover's east. Don't be surprised to see the rover trundling toward that nexus in the weeks ahead. The brightest of these disparate surfaces consists of some material that must be solidly compacted (orbital scans show that it retains heat longer than its surroundings). To the lower left is terrain with relatively few impact craters — and those appear muted, as if mostly eroded or mantled with a thick coating of dust. And the tract to the lower right looks peppered with craters, suggesting it might be oldest of the three.

Milkovich seemed almost apologetic about the quality of the image taken yesterday. To snap it, MRO had to roll 41° to one side, well beyond its usual 30° limit. Such an oblique view both reduced the resolution and introduced more atmospheric dust along the line of sight. She adds that notes that HiRISE has two opportunities to get much better views of the landing site within the next two weeks.

11

11

Comments

Peter

August 8, 2012 at 8:20 am

In the description of terrains, is the first "lower right" meant to be "lower left"?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mark Looper

August 8, 2012 at 8:54 am

It is regrettable, but commendable, restraint on the part of mission planners that they won't send MSL to "check out the piles of wreckage"; I can imagine (say) hydrazine really mucking up the sensitive chemical detectors that are looking for carbon-containing compounds that may or may not be there in infinitesimal concentrations. Well, at least we'll get overhead views from a safe distance.

By the way, did you all see the "Joy of Tech" cartoon on landing day about all these "supporting players"?

http://www.joyoftech.com/joyoftech/joyarchives/1724.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.

George Brewer

August 8, 2012 at 11:47 am

Would be nice to see the landing ellipse superimposed on the image for side-by side comparison. I'm sure NASA or JPL has done this. I just haven't found them yet.

Kudos to S&T for the quick post on the landing. After watching the JPL folks, I stopped by to see what you folks had.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kelly Beatty

August 8, 2012 at 1:47 pm

Peter... yes, of course it's lower-left. now fixed, thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

August 8, 2012 at 3:25 pm

So we send a $2.5 billion dollar plutonium powered robot 350 million miles and some are tempted to go "check out piles of wreckage”? I can look out my window for that! Let’s go get some real science done and have some fun to boot. JPL boys and girls, well done again and, by all means, head for the most interesting terrains you can see.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

August 8, 2012 at 3:30 pm

So we send a $2.5 billion dollar plutonium powered robot 350 million miles and some are tempted to go "check out piles of wreckage”? I can look out my window for that! Let’s go get some real science done and have some fun to boot. JPL boys and girls, well done again and, by all means, head for the most interesting terrains you can see.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mark Looper

August 8, 2012 at 7:00 pm

Well, Bruce, it might be applied rather than "real" science to go study how a heatshield fared during atmospheric entry, but since applied science enables the design of hardware that will survive to do "real" science, it is not merely idle (small-"c") curiosity that might motivate mission planners to send a rover on such a detour. Opportunity did so with its discarded heat shield, though that team waited until almost a year into their 90-day mission to spare the time:

http://www.space.com/638-mars-rover-wanders-littered-landscape.html

Maybe I shouldn't have titled my earlier post as I did...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mike W. Herberich

August 8, 2012 at 8:45 pm

Both, curiosity and Curiosity rule! For the big "C", time will tell, for the small one time has told already, over and over again, and will continue to do so. Never mind about a cat killed here and there, but rather commemorate those humans who have been killed on the way.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

August 8, 2012 at 10:10 pm

Mark, I was attempting to make a humorous point about mission objectives, sorry if I offended any aerospace engineers. I had no intention of implying that the steely eyed rocket people who pulled this off aren’t doing “real” science. Without them clearly none of this could have occurred. You make a good point about the earlier use of Opportunity, but as one of a pair of much less expensive rovers checking out the heat shield of one of them became logically practical only after the first objectives had been checked off. Also, no “crime scene" investigation is called for here, since the crime of failure happily has not occurred. (Nothing to see here folks, move along, please. 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

August 9, 2012 at 6:44 am

Oh, and before any geologist types object to my “nothing to see here” joke, I meant the “piles of wreckage” of course. Looking closely at the SUCCESS scene photo at the bottom part of the lighter colored Terrain 1 I see what to my amateur geologist eyes look like wave cut terraces! Is Terrain 1 lower in elevation that the other terrains? If so the rocket guys may have landed right next to the shore of an ancient Marian bay! Kudos to the site selectors, for Gale truly is a target rich environment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

jaime

August 9, 2012 at 3:00 pm

Excelent photo

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.