Every February, amateur astronomers flock to a dark-sky site in the Florida Keys for a week of stargazing at the Winter Star Party.

Driving south along U.S. 1, you’ll reach the end of the mainland and enter the Florida Keys, where the road becomes the Overseas Highway. Shortly after Marathon, an amazing feat of engineering — the Seven Mile Bridge — deposits you on Little Duck Key. A smidgen farther south and you arrive at Scout Key, home to Camps Wesumkee and Sawyer, girl- and boy-scout camps, respectively.

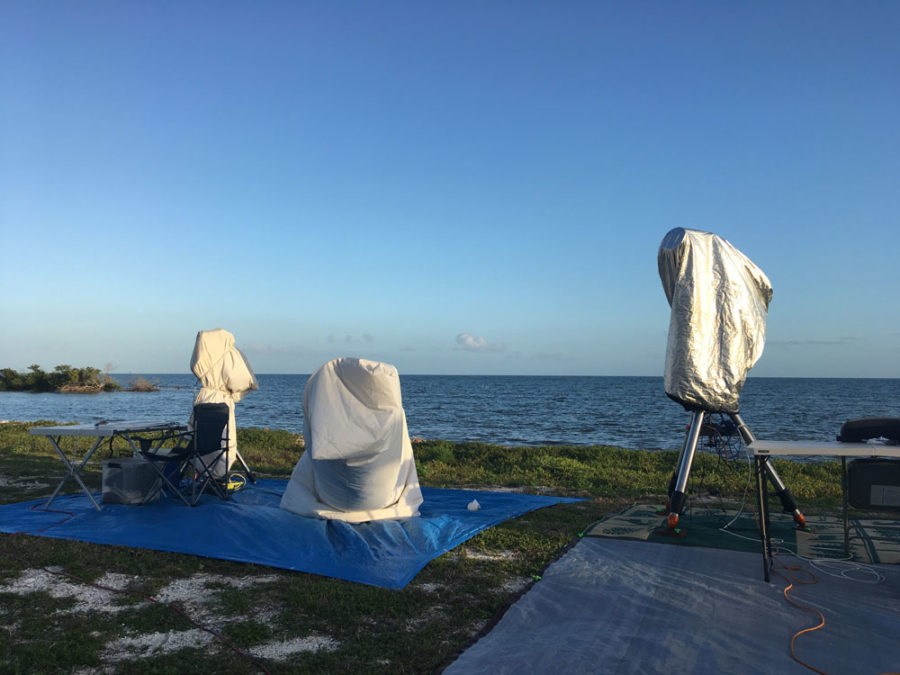

Were you to get there during a new Moon week in February, you’d come across a bewildering array of telescopes of all sizes, RVs neatly parked, tents scattered along the shoreline. That’s the scene that greeted me as I rolled in. I’d arrived at the Winter Star Party (WSP).

Diana Hannikainen / S&T

Russ Brick, president of the Southern Cross Astronomical Society, took me on a golf cart ride upon my arrival. After Hurricane Irma battered the Keys in 2017, the WSP had to relocate in 2018, but returned to the Keys in 2019. As we puttered around, Russ pointed out the remnants of the destruction incurred by the hurricane. Irma wiped out most of the lush trees that used to pepper the area, though some are slowly growing back. “The only good thing about it is that now there’s more unobstructed shoreline for people to set up their tents,” Russ reflects. Attendance also suffered, but as with the vegetation, participants are starting to return. This year, nearly 400 amateur astronomers and vendors registered, down from the sell-out number of 600, but significantly up from the last two years.

As Russ returned to his duties — in addition to nighttime observing, solar observing and talks are scheduled for the daytime — I wandered the grounds, hoping to note where the shiny instruments — and their operators! — were located before darkness fell and all would be swallowed up by the inky Florida night.

Prepping for a Dark Night

I chatted with several people as they were setting up in anticipation of what was promising to be an amazing night. Some had been coming to the WSP since its inception more than three decades ago, while others were there for the first time. Attendees tinkered with reflectors and refractors, imaging equipment, binoculars, monoculars — you name it, if it could in any way enhance your view of the sky, it was there.

Diana Hannikainen / S&T

Dan Doyle was busy setting up imaging equipment on a table next to his 6-inch refractor. A book on telescope-making sparked his interest in astronomy in high school. But life took over and Dan had to set his extracurricular activities aside. About 12 years ago he discovered the Winter Star Party, relaunched himself into astronomy, and has been coming ever since.

The first two nights had been windy, and so Dan (and many others) perused the skies with binoculars. But the previous night had been a great one and he observed with his scope. “We started with Orion because that’s right up above us when the Sun sets, and it’s just incredible. There are so many objects in Orion, my favorites are the Horsehead and Flame Nebula. Then there’s the Whirlpool Galaxy and Omega Centaurus. It’s tremendous. You just don’t know where the time goes,” Dan enthuses.

That was the litany I heard from many an observer.

Bill Arden was a first-timer at the WSP, but insisted it wasn’t going to be his last. “This is such a friendly group,” he told me, and after just a couple of hours on the ground there I could but concur. Everyone was eager to share their experiences — and the view through their eyepieces — with anyone who drifted into the immediate vicinity of their equipment.

Observing Begins

When darkness fell and I drifted into Darren Drake’s and Dan Joyce’s observing area, they offered me a peek through their eyepieces. With Darren’s 18-inch Dob I saw Uranus (it’s so green!), Sirius’s Little Pup (I could split it!), the planetary in M46 (it’s so cute!), the Spirograph Nebula (I can see the pink!), Comet PanSTARRS (wow!). While I’m exclaiming at the targets, Darren tells me about the astronomy summer camp he runs in Michigan. During the day, kids learn about astronomy from amateur astronomers and educators, and when darkness falls they get hands-on with telescopes. I think to myself: Lucky kids!

Denise Woody is imaging M42 with an easy-to-use tracker and an 85-mm camera lens. She points out Barnard’s Loop on the screen, then zooms in on the Horsehead and Flame Nebula (I’m getting the picture that these are favorites). “It’s really amazing what you can do with very light equipment,” she tells me, and I agree — the picture is very clear and sharp.

Time to go check out the 24- and 32-inch behemoths that I’d spotted earlier. As I walk toward the eastern end of Camp Wesumkee, I take a few minutes to absorb the atmosphere. It’s all so overwhelming — the people, the enthusiasm, the whir of trackers, the thrumming of generators. We’re at a dark-sky site, and on moonless nights, it’s truly dark. I listen to the waves gently lapping and I notice a bright light dancing on the water. I had to blink several times. The source of that light . . . was Canopus! I couldn’t believe a star was responsible for that river of light.

Diana Hannikainen / S&T

At John Pratte’s 32-inch Dob, Mike Lockwood is perched on the ladder, some six feet or so above the ground. A crowd has lined up to view the Flame Nebula (there it is again) through the eyepiece of this magnificent instrument. One after another people climb the ladder, peer through the eyepiece, and inevitably exclaim with pure wonder. “Oh wow” and “Holy moly” and “That’s spectacular” float into the darkness from up high. For those who want a spectacular view but might suffer from vertigo, Kirk Collins’s 24-inch is set up nearby. John and Kirk generously shared their turf with all of us eager viewers throughout the night.

I ambled over to find out more about an interesting-looking apparatus I’d espied earlier. I discover it's an asymmetrical binocular telescope made from two 5-inch f/5.5 individual units with achromatic lenses. Its owner, Brent Carter, had assembled it himself in his quest for a comfortable viewing experience — this model, he added, “provides a very relaxing observing mode with no eye-strain whatsoever.” Clusters are gorgeous viewed through it, and the Double Cluster was positively spectacular.

Meanwhile, back at the 32-inch, people were enjoying views of the Orion Nebula (M42) with an image intensifier. Yup, the thing sure was bright, just as I’d been warned. Next, we slewed over to the Rosette Nebula and Mike tells me to “drive around it, because it’s big.” And so, gently nudging the Dob, I roll around the edges of the nebula, taking in the palpable structure of alternating dark and bright puffs of nebula embedded in the most delicate wispiness.

Diana Hannikainen / S&T

One of the more amusing aspects that night was that since it was so dark, nobody could make anybody else out. People would come right up and ask to your face, “Are you Mike?” or randomly call out, “Anybody seen John?” to which the answer might be, “Yeah, he’s up the ladder,” or “No, he’s gone round to check out so-and-so’s scope.”

Glorious View

While waiting for Omega Centauri to rise, we bagged the Needle Galaxy (it’s really thin!), Thor’s Helmet (I saw the filaments!), M64 also known as the Black-Eyed Galaxy (obviously), NGC 2392 (its complex structure was clearly discernible), the Whirlpool Galaxy (and its companion), The Ghost of Jupiter (I could see color!).

And then, finally, Omega Centauri rose and hovered above the Straits of Florida. I saw the globular cluster with the unaided eye — it was faint, but distinctively fuzzy. I moved on to 10×50 binoculars, to the asymmetrical binos, to the 24-inch, to the 32-inch. In each instrument, this glorious conglomeration of some 10 million stars showed off its best side. In the smaller ones, I could almost feel the weight of those millions of stars, while in the larger ones, I could make out individual stars and streamers of stars that curled around the edges of the celestial ball.

It was time to go. Reluctantly I tore myself away from that sight.

I’d asked Dan Doyle earlier in the afternoon if he’d made observing plans for the night and he said, “Oh, yeah, it’s going to be a long night, look at the sky, it’s beautiful, there’s no wind tonight. It’s going to be the primo night of the event.”

And it was. It sure was.

Diana Hannikainen / S&T

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.