Observations from NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) have rekindled interest in dust clouds seen along the Moon’s day-night terminator.

NASA

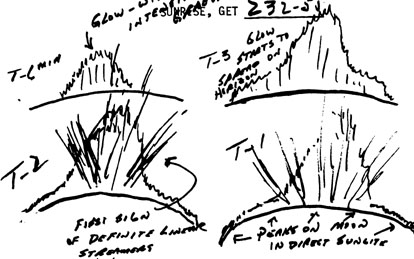

In 1968 NASA’s last robotic lunar lander, Surveyor 7, took images of a strange twilight glow along the lunar horizon during dawn and dusk. It was strange because twilights, like those on Earth, are caused by an atmosphere scattering light — and the Moon doesn’t have an atmosphere. A few years later, Apollo astronauts saw these glows as well as they circled the Moon.

Eventually, researchers concluded that the strange day-night glows must be caused by dust particles that had been thrown up with enough height and density to scatter sunlight. Dust clouds aren’t rare on Earth or Mars, which have atmospheres, but they are when talking about an airless body like the Moon.

More than 40 years later, we are still struggling to understand the nature of these dust particles, and how they lift from the surface and jump so high. Subsequent missions since Apollo have both confirmed and refuted the dust cloud’s presence, as well as given different measures of the density and concentration. Now, the newest data gleaned from NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer has provided researchers even more to think about.

What Did LADEE See?

Using LADEE’s Lunar Dust Experiment (LDEX), which detects particles once they ionize after impacting the spacecraft, Mihály Horányi (University of Colorado) and colleagues reconciled a number of details concerning the distribution, origin, and size of the dust particles that float above the Moon.

Daniel Morgan and Jamey Szalay

First, they saw that the dust cloud is much closer to the Moon’s surface and less dense than previously thought. They also confirmed the dust’s origin: comets. LADEE recorded an asymmetric dust cloud instead of a circular one along the Moon’s day-night terminator. If the dust is coming from asteroids, as was originally believed, then the resulting impacts would produce a much weaker and more symmetric cloud, due to the particles’ near-circular orbits as they move inward toward the Sun. In addition, the team also found that the cloud increases in density during annual meteor showers, such as the Geminids, which are streams of particles spread along comets’ orbits.

Static Levitation?

It’s still unclear what keeps the dust suspended so far about the lunar surface, or why it’s concentrated along the terminator. For example, the most generally accepted theory, involving static levitation, might be at odds with the observed change in cloud density and the dust’s origins.

With no atmosphere, the Moon’s surface is subject to direct bombardment by the solar wind, streams of gas from the Sun that are loaded with particles such as negatively charged electrons. When the wind hits the surface in a nighttime area, it negatively charges the dust. However, sunlight can displace these electrons, creating a positive charge. Once an area becomes charged, the dust particles begin to leap about, attempting to get away from their like-charged neighbors. Along the Moon’s terminator the dust is whipped into a chaotic frenzy as it’s pushed and pulled into night and day (negative and positive charges). This “atmosphere” would then be able to scatter light, causing that twilight glow.

The static-levitation model, first proposed in 1973 by David Criswell (then at the Lunar Science Institute) and others, does have some flaws, however. Although it can account for how dust hovers over the surface of the Moon, it cannot explain how some particles rise up to 100 km or more.

Timothy Stubbs (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center) and colleagues suggest a “dynamic fountain” model to account for these higher-altitude plumes, where certain dust particles are shot up through channels of enhanced charging — much like what happens when you rub your head with a balloon, hold it over your head, and see some strands of hair strain up to the balloon for a while before falling back down. Stubbs admits that the dynamic fountain also has flaws, as it has made assumptions about the electrostatic interactions on the Moon’s surface.

It’s the best theory for now, but researchers like Stubbs will need much more data in order to really pinpoint the mechanisms at work. We have no definitive answers yet, but the LADEE results have reenergized a decades-old debate about this mysterious lunar phenomenon.

References

M. Horányi et al. “A permanent, asymmetric dust cloud around the Moon.” Nature. June 17, 2015.

T. Stubbs et al. "A dynamic fountain model for lunar dust." Advances in Space Research. April 2005.

5

5

Comments

June 17, 2015 at 8:25 pm

Enough already with the 'Artists Conception' of what I want to see a photo of, if there is one.

Many years ago when cameras were hand loaded it made sense to hire someone to draw what was difficult to photograph. Those days have been over for more than a century. WHEN are you media folks going to get with the times? I would be less concerned about this, if there were not a very great difference between data and and art. Art does not contain the new information. It presents the old ideas in bright, splashy snippets that look like information, but is actually content free filler material for the blank space where the new information is supposed to be PUBLISHED.

As frustrating as it is for those who know the difference, and realize we are being habitually starved if information, think briefly of the effect on those who DON'T know the difference. They think they are being informed, when in fact, at best, they are being entertained. Here is the serious question : How is it Sky and telescope does not appreciate the difference between science and art?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter Wilson

June 18, 2015 at 11:07 am

Artist's conceptions are not supposed to be immaculate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

June 18, 2015 at 7:10 pm

A quick search for "Horanyi et al 2015 LADEE Nature" yielded a link to a preview of the Nature article, with all eight figures from the full article:

www dot nature dot com/nature/journal/v522/n7556/full/nature14479.html

Sky and Telescope is a general interest publication. So long as an artist's conception is clearly labeled as such (and S&T is conscientious in this regard), it can help a lay reader to understand the phenomenon under discussion.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Faye_Kane_girl_brain

June 26, 2015 at 6:39 am

> Enough already with the ‘Artists Conception’ of what I want to see a photo of, if there is one.

Well, until you became disturbingly upset about "art" and "information," I was about to make the same point.

In a post that suddenly disappeared, an S&T staff guy said:

> An artist’s conception can help a lay reader to understand the phenomenon

Yeah, so will the paintings in My Little Golden Book of the Planets, but I don't want to see them in S&T.

When I saw the picture at the top, I thought, as always, "Cool! But lemme see... is this a real photo or someone's artwork I need to ignore?"

You'd think I'd be used to disappointment by now.

Even SciAm wastes the first two pages of every article on a thrilling, dramatic, useless painting of what the article is about. Yes, Chesly Bonstell's paintings were magnificent, but only when they were in article titled, "Chesly Bonstell's Magnificent Paintings." You actually had that article once, and I loved it.

Next, I suppose Science and even Astrophysical Journal. will be doing it.

Look, if you need a graphic for layout aesthetics, use a graph that contains information. Even a photo of the probe's launch vehicle or the bearded, balding principal investigator would be better. When I want breathtaking paintings, I'll go look at the covers of all my old sci-fi paperbacks.

--Faye Kane

My naked pix

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Faye_Kane_girl_brain

June 26, 2015 at 6:48 am

> An artist’s conception can help a lay reader to understand the phenomenon

So will the paintings in My Little Golden Book of the Planets, but I don't want to see them in S&T.

-Faye

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.