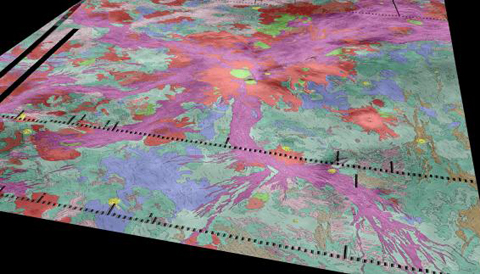

Hotspots on Venus might be researchers’ long-sought evidence for active volcanoes.

Credit: Ivanov / Head / Dickson / Brown University.

Although Earth and Venus were born similarly, with comparable sizes and atmospheres, they eventually bloomed into the two very different worlds we see today. For example, Venus’s atmosphere is remarkably thick and made almost entirely of carbon dioxide, whereas ours is much thinner and contains a more balanced mixture of nitrogen, oxygen, and carbon dioxide. Another difference lies in the planets’ crusts. Earth’s is divided into sections — called plates — and has parts that are very old and others that are new (due to recycling by plate tectonics). Venus has a single, relatively young crustal plate that covers its entire surface.

A young age suggests that something must have destroyed the old exterior and created a new crust. Researchers are rather confident that this event was a massive volcanic eruption (or eruptions) about 600 million years ago, and the question that remains now is whether the volcanoes are still active today.

Planetary scientists have searched for evidence of active eruptions for years but haven’t found definitive proof. Last year, Eugene Shalygin (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany) and colleagues reported that the European Venus Express orbiter had identified strong signs of active volcanism on the planet’s surface, as we covered at the time. Shalygin’s team has now published their full study on June 17th in Geophysical Research Letters.

Hotspots

Credit: Shalygin & others / Geophysical Research Letters

As noted in last year’s S&T report, the spacecraft’s Venus Monitoring Camera (VMC), which takes pictures in the infrared that can monitor temperature changes at the surface, captured images of areas whose thermal brightness fluctuated (they became hotter and then cooler). These hotspots were located in the Ganiki Chasma, a group of young rift zones — narrow, deep fissures caused by deep-seated volcanic convection. Earth exhibits similar relationships between hotspot activity and rift zone locations — even the dimensions of Venus’s hotspots match those on Earth.

From these observations, the researchers conclude that these brightness spikes were likely caused by active volcanoes; when they erupted, they spewed out hot matter, and the VMC caught their infrared footprints on camera.

The Big Picture

“[These] new data gives even more evidence in the direction that Venus is active now,” explains Linda Elkins-Tanton (Arizona State University). “In fact, I’d be really surprised if we find out that it isn’t.” Elkins-Tanton, who was involved in a 2010 study of Venus that looked at non-infrared radiation emitted from the planet’s surface, hopes that the new data will provide additional impetus to continue to visit and study Venus.

“Some people might wonder why we care about Venus’s volcanoes,” she explains. “If Venus is still being resurfaced volcanically, then that means some of its material is being recycled. On Earth we have the carbon cycle to replenish our material. Venus is not habitable, and we are. So we need to better understand what caused Venus to be so different from Earth in order to understand why Earth’s cycling promoted life and Venus’s didn’t.”

Reference

Eugene Shalygin, et al. “Active volcanism on Venus in the Ganiki Chasma rift zone.” Geophysical Research Letters, June 17, 2015.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.