Stay up late and you'll see the return of one of the sky's most familiar asterisms, the Summer Triangle. Firefly nights under the arch of the summertime Milky Way will soon be here.

Stellarium

Every season has its celestial bellwether. Orion's appearance in the east in November heralds the coming of winter; the Great Square in August the crunch of fall leaves, and the orange twinkle of Arcturus in March the promise of spring. We look east to see what's trending, what will be the next big thing.

On a recent evening while walking the dog, I turned east and caught sight of the Summer Triangle, a giant asterism that practically shouts "Summer's on the way!"

Three of season's brightest stars — Vega, Altair, and Deneb — mark its vertices.The first to appear in the east and also the brightest is Vega, pushing up between leafless trees in April. It's followed a couple weeks later by Deneb and then finally Altair. That's the order at mid-northern latitudes, but from a Caribbean beach, Altair rises shortly before Deneb. Pop down under to Perth, Australia, and their order is completely reversed, with Altair rising first followed by Vega and Deneb last.

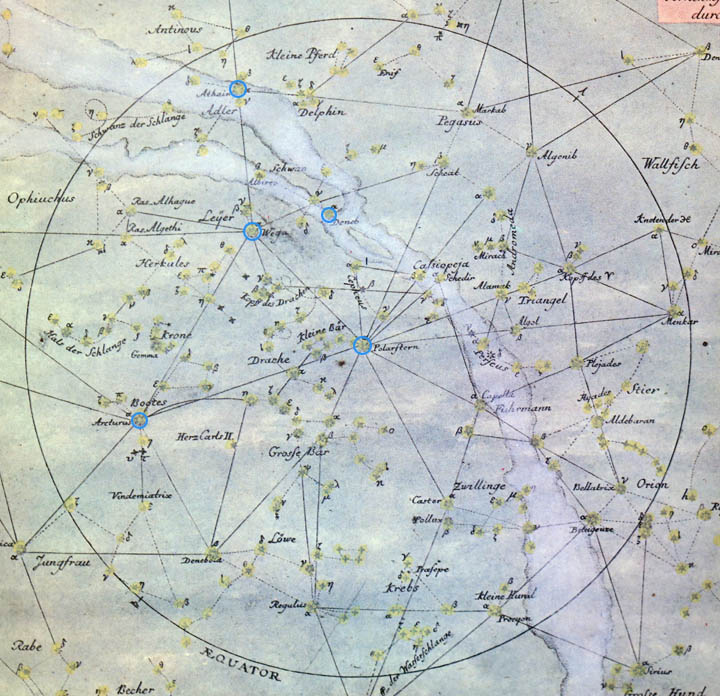

J. E. Bode's Sternatlas

The earliest written reference to the Summer Triangle dates back to Austrian astronomer Johann Joseph von Littrow's Atlas des gerstirnten Himmels (Atlas of the Starry Heavens) published in 1839. On page 4 he writes (translated from German):

" . . . you can immediately recognize a very striking, large, isosceles triangle in the sky, which is formed by three stars of the first magnitude, namely through Vega, Deneb, and Altair."

While Littrow didn't call it the Summer Triangle, he was clearly was on the right track. The triangular trio made a brief appearance again on page 41 in the 1913 guidebook The Stars and Their Stories: A Book for Young People by Alice Mary Matlock Griffith.

Bob King

Fast forward to the late 1920s, when Austrian astronomer Oswald Thomas referred to the three as the "Grosses Dreieck" (Great Triangle); by 1934 it's the "Sommerliches Dreieck" (Summerly Triangle). England’s famous astronomy popularizer Patrick Moore, who passed away in 2012, called the group the Summer Triangle in his books and lectures beginning in the 1950s.

One hundred years later and backed by the power of the internet, the figure and name have become much more familiar to the public. While lacking the cachet of, say, an Orion's Belt or Big Dipper, word's finally getting around that the triad of Vega, Deneb, and Altair makes a great place to begin to find your way around the summer sky.

In late May, the entire asterism clears the eastern horizon around midnight with radiant Vega leading the way. Vega heads up the diminutive constellation Lyra, the Harp, a half dozen dim stars in the shape of a small harp or lyre. If you've ever wondered how to pronounce the name Vega, you're not alone. I say VEE-guh but most people prefer VAY-guh. If I'm with a group of beginner skywatchers I tell them either way is fine. But the truth is that VEE-guh was chosen as the preferred pronunciation back in 1941 by a committee of the American Astronomical Society.

Bob King

To find Deneb, the brightest star in Cygnus, the Swan, or Northern Cross, reach your balled fist to the sky and look "two fists" to the lower left of Vega. Three fists to the lower right of Vega will take you to Altair in Aquila, the Eagle. Vega, Deneb, and Altair are all easy to see even from a middle-sized city and suburban areas, and each is a unique and fascinating star.

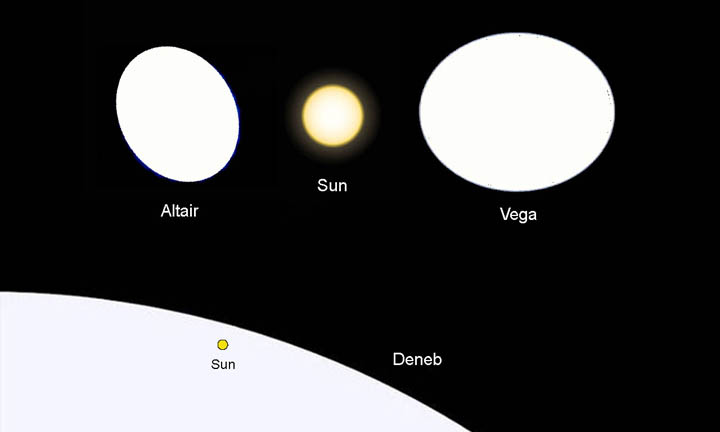

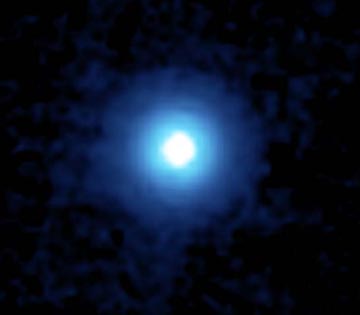

NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

Vega spins so rapidly it's 23% fatter at the equator than the poles. We also view the star looking directly over one of its poles, not from the side. Deneb is frighteningly large and by far the intrinsically brightest of the three stars. Although of apparent magnitude +1.25, were Deneb placed at Vega's distance it would shine at magnitude –7.8 — almost as bright as a half Moon — and cast obvious shadows. Deneb means "tail" in Arabic and refers to its position as the tail of the Swan.

Altair isn't only a bright nearby neighbor at just 17 light-years from Earth but also spins rapidly, completing one rotation in 8.9 hours. Whirling at 240 kilometers per second (149 miles per second), or 66 times faster than the Sun, it's spinning at a significant fraction of the speed required to tear itself apart. I like to think of my typical workday as nearly equal to one spin of Altair.

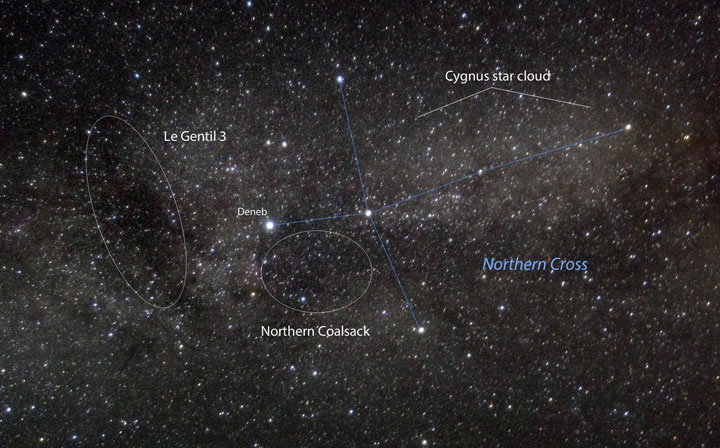

An additional treat awaits the eyes of rural observers or those who make a drive to the country. The Summer Triangle frames a bright section of the Milky Way, and with the Moon out of the way for the next week, you can watch this wonderful, star-rich band mount in the eastern sky. Its most prominent feature is the Cygnus Star Cloud, a better-than-fist-wide oval patch shimmering with starriness between Deneb and Albireo at the foot of the Cross. Binoculars are all you need to get lost among the stellar hordes.

Bob King

A short distance north of the star cloud, you'll see the darker side of the Milky Way in two huge dark nebulae, thick clouds of interstellar dust that absorb and block the light of myriad background stars: the Northern Coalsack, a cloud of cosmic dust an estimated 600 light-years away, and the long, parenthetic Funnel Cloud Nebula.

Bob King

Every time I see those three bright stars carry up the scintillatious Milky Way, I get jazzed for summer nights ahead. You, too? I figured so.

5

5

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

May 26, 2017 at 5:44 pm

Bob, your wide field photo of the Summer Triangle rising through the trees is really beautiful.

It is surprising that the Summer Triangle asterism is of such recent historical origin. I wonder if it was less obvious when everybody lived under light-polluted skies, although for more than half of every lunar month moonlight washes out the fainter stars, accentuating the brighter ones.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

May 26, 2017 at 5:45 pm

Whoops! I meant to say, "when everybody lived under skies that were not light-polluted".

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

May 27, 2017 at 10:39 am

Hi Anthony,

I'm happy you liked the photo - thanks! I agree -- I think people have noticed the Summer Triangle for a long, long time but never wrote it up. I'd compare it to the clouds, which weren't named until Luke Howard set about the task in the early 1800s.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob

May 26, 2017 at 11:25 pm

Bob King, another great article. Your presentation of the Summer Triangle asterism is most interesting.

Thank you.

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

May 27, 2017 at 10:34 am

Thanks Bob-Patrick! One of my favorite parts of the sky. I enjoyed trying to get to the bottom of the name's origin.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.