Contact:

Alan M. MacRobert, Senior Editor

617-758-0245, [email protected]

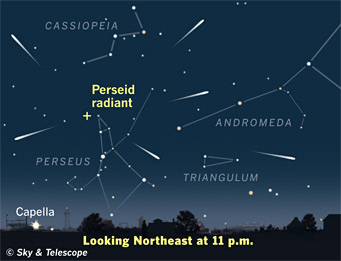

The Perseid meteors appear to stream away from the shower's "radiant" point near the border of Perseus and Cassiopeia. Under dark-sky conditions, you may see an average of one a minute around the time of the shower's peak. Click image for a publication-quality graphic. Sky & Telescope illustration |

The Perseid meteors should put on the peak of their yearly display late this Saturday night and early Sunday morning (August 11-12, 2012). “December's Geminids often outperform them by a bit,” says Alan MacRobert, a senior editor of Sky & Telescope magazine, “but the Perseids are probably the most-watched meteor shower, because they come in the warm vacation season."

Like all meteor showers, the Perseids are named for the constellation from which they appear to radiate. Perseus will hang low in the northeast early on the night of the 11th. The shower will really get underway after 11 or midnight local time, predicts Sky & Telescope, when from a dark site you may spot one or perhaps two Perseids a minute on average. The rate should increase as Perseus gains altitude in the early hours of the 12th. A thick waning crescent Moon will rise around 1 or 2 a.m., “but its glare at this phase will be no big problem,” says MacRobert.

Watch associate editor Tony Flanders guide a tour of the Perseid meteor shower on this week's SkyWeek, also available on Youtube.

Though the Perseids are named for Perseus, the constellation has nothing to do with where the meteors were born. Most meteors come from comets shedding dust and debris as they travel through our region of the solar system. We see a shower when Earth, in its annual travels around the Sun, passes through a meteoroid stream strung along a comet’s orbit. It’s only from this perspective that we see the Perseids appearing to come from Perseus.

And, that’s only if you trace their paths backward far enough across the sky. The meteors can flash into view anywhere in the sky as long as Perseus is above the horizon. “So,” says MacRobert, “the best part the sky to watch is wherever is darkest, probably straight up.”

The Perseids are pieces of Periodic Comet Swift-Tuttle. As Earth passes near the comet's orbit, tiny chunks of debris — mostly the size of grains of sand, but some as large as peas or bigger — enter the atmosphere at 60 kilometers per second (134,000 mph). Starting at an altitude of about 100 km (60 miles), a meteoroid compresses the air in front of it like water before a speedboat, creating a white-hot shock wave. This is what you mostly see — not the little bit of debris itself.

Meteors that come from comets are more like dust clumps than rocks. Even big ones are too fragile to make it down to the ground as meteorites — unlike pieces of rock and iron, which come from asteroids.

Earth passed closest to Comet Swift-Tuttle in 1992, and the Perseids put on particularly spectacular displays during the years around then. The shower has since returned to normal. The comet won't approach so close again until around 2125, but that doesn't mean this year's Perseids won't be worth finding your own patch of dark sky. Try to get as far from city lights as possible, bring a reclining lawn chair to lie back in, and be patient. And don't drag out your telescopes or binoculars; they restrict your field of view too much for meteor-watching. For this, says MacRobert, ”your naked eyes work best.”

For skywatching information and astronomy news, visit SkyandTelescope.com or pick up Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy. Sky Publishing (a New Track Media company) was founded in 1941 by Charles A. Federer Jr. and Helen Spence Federer, the original editors of Sky & Telescope magazine. In addition to Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.com, the company publishes two annuals, Beautiful Universe and SkyWatch, as well as books, star atlases, globes, and other fine astronomy products.

0

0