Break out your binoculars or a small telescope, we’ve got a busy week ahead! Watch as a bright asteroid approaches Earth, the Moon steals a star, and Comet ATLAS’s last hurrah.

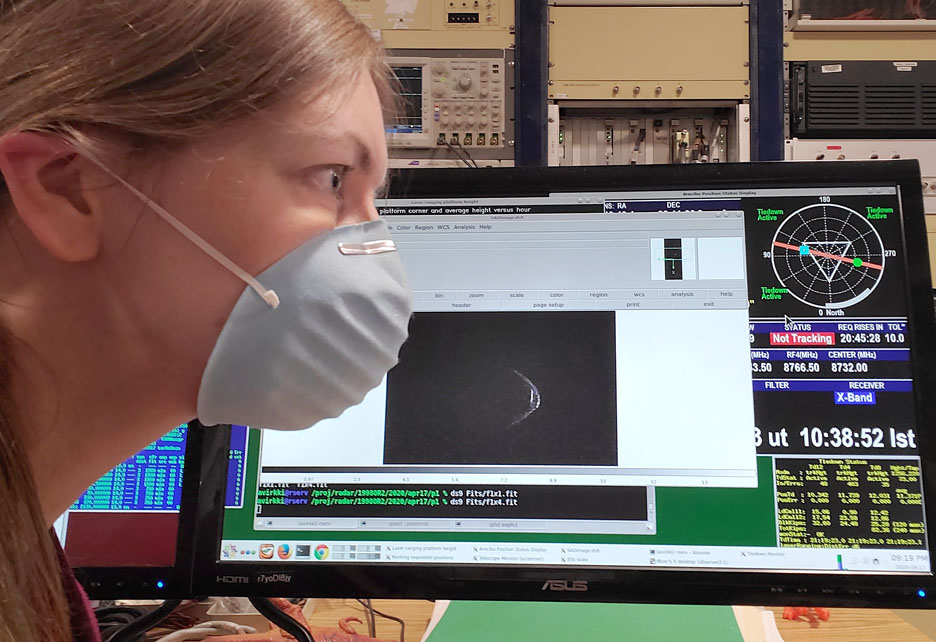

Arecibo Observatory / NASA / NSF

Is it a coincidence that asteroid (52768) 1998 OR2 looks like it's wearing a mask in this image obtained with the Arecibo radio telescope? Or has COVID-19 completely changed how we see the world? Either way you'll want to make a date with this large near-Earth and potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) very soon. On the morning of April 29th it will safely zip past Earth at a distance of 6.3 million kilometers (3.9 million miles), or around 16 times the distance to the Moon.

Courtesy of Anne Virkki

Other asteroids have swung much closer to Earth but this pass is noteworthy because 1998 OR2 is much bigger than most in its class — it will become bright enough to see in a small telescope.

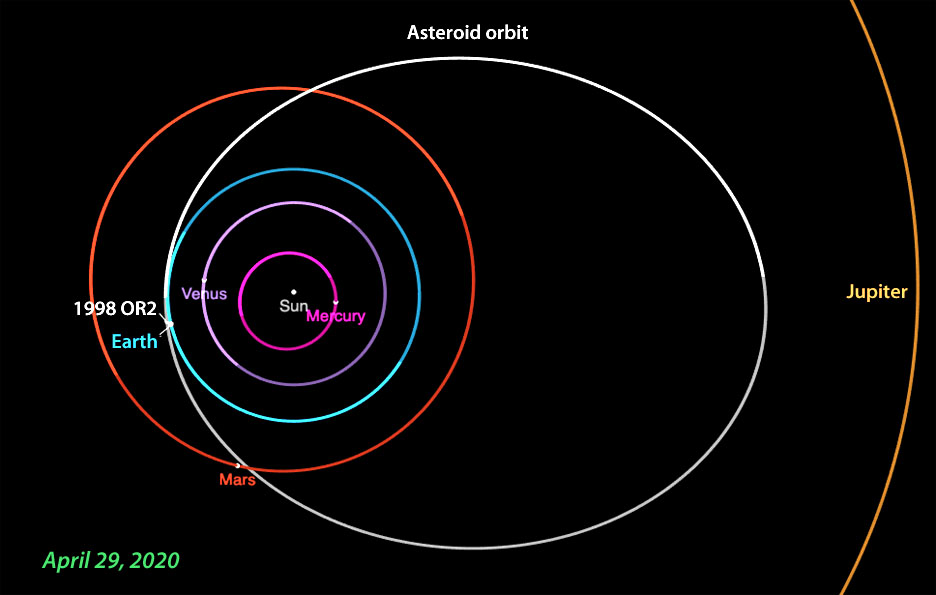

Discovered by the robotic Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) survey on Maui's Haleakalā in July 1998, the object is a relatively rare L-type stony asteroid that swings to within spitting distance of Earth's orbit at perihelion out to a chilly 3.8 a.u. (around 570 million kilometers) at aphelion. Assuming its reflectivity is similar to other stony asteroids, astronomers estimate 1998 OR2's diameter at around 2.1 kilometers (1.3 miles), making it one of the larger PHAs known.

NASA / JPL-HORIZONS

What to Expect

On April 22nd the asteroid glows at magnitude 12.0, bright enough to see in a 6-inch telescope, but it will peak around magnitude 10.8 during the close-approach window from April 30th through May 3rd. Even under suburban skies a 4.5-inch telescope should capture this celestial roadrunner in the early evening sky as it races across Hydra and Sextans at more than 30,000 km/h in relation to the Earth (132,500 km/h in relation to the Sun.) Ardent observers can track the asteroid well into May as it continues through Centaurus while slowly fading. If you don't have a telescope our friend Gianluca Masi will live-stream 1998 OR2's appearance on April 28th starting at 2 p.m. EDT (18:00 UT).

Ingvars Tomsons / CC BY-SA 4.0

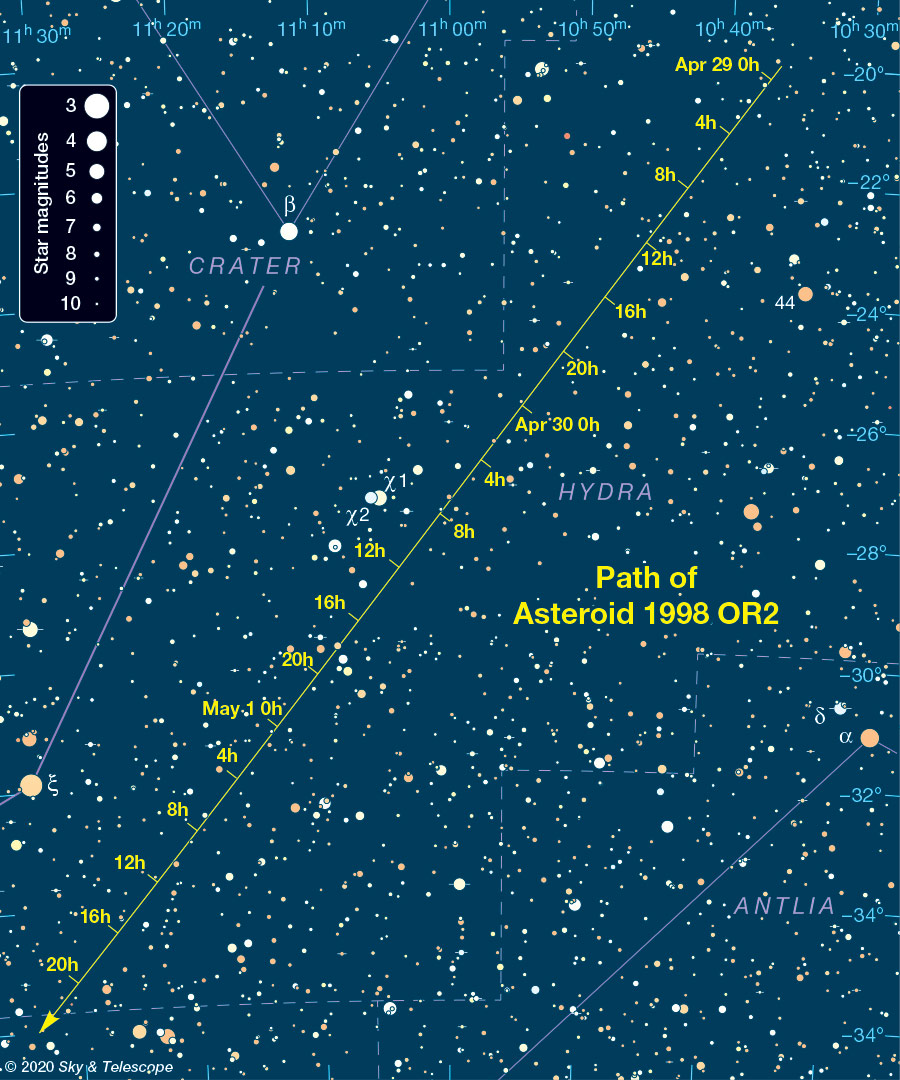

We have two charts that you can use to find and follow the asteroid: one for April 25–28 and the other for April 29–May 1. Each is marked at intervals of 4 hours Universal Time. Be sure to subtract 4 hours from the times shown for Eastern Daylight Time; 5 for Central; 6 for Mountain; and 7 for Pacific. You'll also find charts for a more extensive selection of dates at Gideon van Buitenen's 1998 OR2 link on his astro.vanbuitenen.nl site.

Within a few days on either side of closest approach the asteroid's apparent motion will reach ¼° per hour (15 arcseconds per minute), fast enough to discern its movement in just a couple minutes with a magnification of 100×.

Sky & Telescope

Set a Trap

To spot the asteroid, set a "trap" along its path at a selected time and wait for it to arrive. Bright stars or distinctive star patterns make ideal places to corral the object. The asteroid will look exactly like a star but move slowly to the southeast.

Once you find it, go along for the ride. Picture an irregular, flying roundish island spinning once every 3.2 hours as it saunters around the Sun in 1,344 days. Or imagine a date far in the future when the asteroid could potentially strike the planet, momentarily filling the entire eyepiece field before merging catastrophically with the Earth.

Asteroid 1998 OR2's next close approach occurs on April 16, 2079, when it will pass more than three times closer, missing Earth by a mere 4.6 times the distance to the Moon.

Moon Takes Out an Eye

On Saturday evening, April 25th, the three-day-old lunar crescent will occult the 3.5 magnitude star Epsilon (ε) Tauri, also known as Ain. The name derives from the Arabic for "eye," and Ain represents The Bull's left eye; the right eye is Aldebaran.

The star will disappear behind the lunar limb in late twilight from locations in the northeastern U.S., including Burlington, Vermont; Boston, Massachusetts; and New York City, while observers in the eastern half of Canada and the Upper Midwest will witness the disappearance in bright twilight (small telescope required!) and reappearance during mid-twilight when binoculars might suffice. By the time darkness falls in western North America the Moon will have left the star behind, but their close proximity will make an attractive binocular sight.

Stellarium

The occultation occurs at the Moon's earthlit limb, where the contrast between star and Moon is most dramatic. Some locations may experience a grazing occultation with the star popping in and out of view from behind mountains and crater walls that project beyond the lunar limb.

Stellarium

If you're not in the occultation zone you'll still get to see the Moon slide just to the north of Epsilon Tau in a beautiful setting that includes the Hyades and Venus. The star is an orange giant 13 times the Sun's diameter and about 150 light-years away. It's orbited by a super-Jupiter, an exoplanet 7.6 times more massive than our own Jupiter. During the International Astronomical Union's NameExoWorlds contest in 2014, when 31 exoplanets received formal names, Epsilon's planet was one of the lucky recipients — it now goes by Amateru, after the Shinto goddess for the Sun, Amaterasu.

Boston — disappearance at 9:44 p.m., moonset before reappearance

New York City — d: 9:55 p.m, moonset before reappearance

Burlington, VT — d: 9:39 p.m., moonset before reappearance

Montreal — d: 9:36 p.m., moonset before reappearance

Thunder Bay, Ont. — disappearance at 9:35 p.m., reappearance at 10:07 p.m.

Duluth, MN — d: 8:46 p.m., r: 8:59 p.m.

Winnipeg, Man. — d: 8:32 p.m., r: 9:01 p.m.

Grand Forks, ND — d: 8:44 p.m., r: 8:55 p.m.

Below you'll find occultation times for several cities (local daylight-saving times are accurate within 1 to 2 minutes). You can also simulate the occultation (or lack thereof) for your location by using Stellarium. In the Sky and Viewing Options window be sure you reduce the default value under Relative Scale to 0.25 so the stars become points. Also, uncheck the Scale Moon box under the SSO tab. Search for the asteroid, zoom in, and run the clock back and forth to recreate the event.

Bye-bye ATLAS?

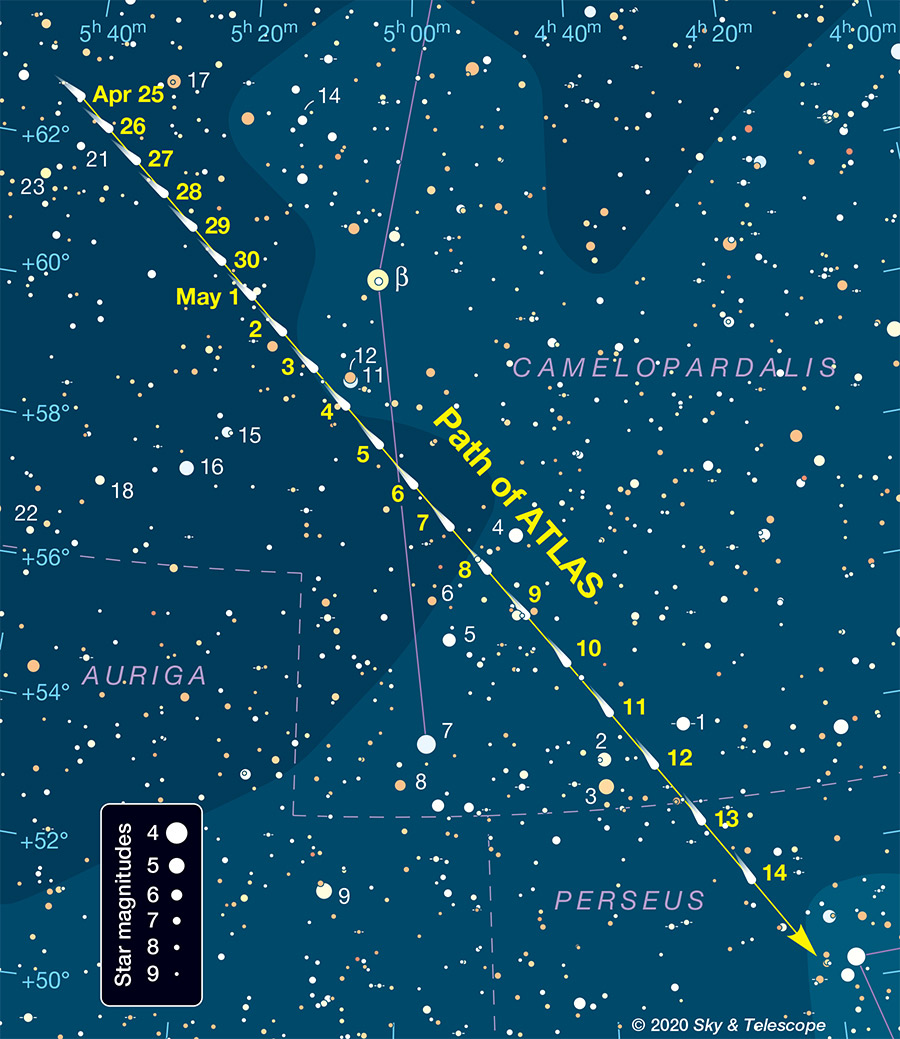

Sky & Telescope

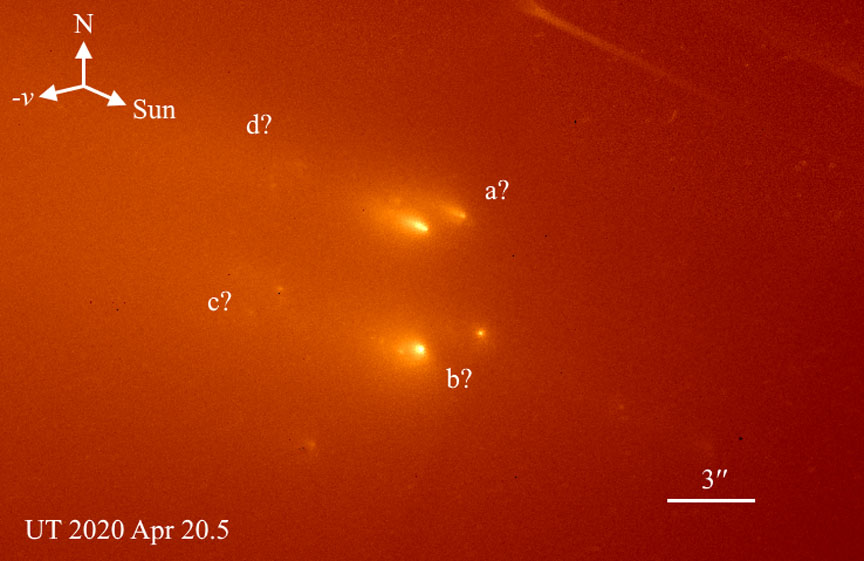

As promised, we have a new chart of Comet ATLAS (C/2019 Y4) to share. This is the comet we'd pinned our hopes on to brighten to around third magnitude before its May perihelion. Sadly, the object continues to fission and dissipate. No one likes to see a potentially bright comet fade away, but its evolution has been fascinating to watch through the telescope.

Quanzhi Ye / NASA / ESA

Recent images from the Hubble Space Telescope reveal several distinct chunks of the original comet's nucleus along with debris clouds of calving fragment cascades. While Comet ATLAS continues to slowly fade — now around magnitude 9.5 with a 4′ to 5′ coma and a faint tail pointing east — it's still bright enough to view in an 8-inch telescope. For how long is anyone's guess!

8

8

Comments

Yaron Sheffer

April 24, 2020 at 3:29 pm

Speeding through space at 30,000 km/h does not make 1998 OR2 a "celestial roadrunner". Fact is, our humble and much bigger planet clocks 108,000 km/h on any given day! With both bodies currently flying side by side around the Sun, I suspect the speeding referred to above is relative to our planet. Indeed, this asteroid should be going faster than Earth in order for it to continue climbing up the solar gravitational well and eventually reach its much greater (and colder) aphelion. Therefore, the absolute speed of 1998 OR2 might well be about 138,000 km/s, or almost 30% faster than the Earth's. This, indeed, makes it a better "roadrunner" than our planet

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

April 24, 2020 at 3:31 pm

Of course, all speeds above should be in km/h, including 138,000 km/h, NOT km/s!!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John-Mosley

April 24, 2020 at 6:22 pm

SkySafari, and perhaps other apps, has this asteroid in its database and you can watch it move across the sky.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 26, 2020 at 10:24 am

Thanks, John for sharing that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Warren-Odom

April 25, 2020 at 10:49 pm

Yes, S&T writers please take note, as a general rule astronomical speeds should always be quoted "with respect to so-and-so," unless obvious in context (such as, "the meteor hit Earth's atmosphere at xxx speed").

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 26, 2020 at 10:28 am

Hi Warren,

Point well-taken! I have updated the article to include its speed relative to both bodies, Earth and Sun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

April 26, 2020 at 10:27 am

Hi Yaron,

Of course I was only looking for a fun way to describe its rapid motion. True, in relation to the Earth, it's only around 30,000 km/h but as you pointed out, in relation to the Sun it's moving MUCH faster, approximately twice the speed of a roadrunner 😉

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

April 27, 2020 at 11:51 am

Hi Bob,

Well, isn't it exciting that our Earth is almost as good a roadrunner? 🙂

We can also note that LEO satellites move at 28,000 km/h. So under more ideal circumstances, such as a REALLY close approach to Earth, and with some help from atmospheric aerobreaking, 1998 OR2 could be captured into an orbit around our planet...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.