A new study estimates the number of interstellar objects that fly through the inner solar system every year, and it could be quite a lot.

ESO / M. Kornmesser

We've been missing small interstellar objects like 1I/‘Oumuamua zipping through the inner solar system, according to Marshall Eubanks (Space Initiatives), who calculates that an average of seven such objects pass inside Earth's orbit each year.

‘Oumuamua attracted attention both as the first interstellar object identified in the solar system and for its enigmatic nature. “The fact that it came so close to Earth implies there are lots of such objects,” says Gregory Laughlin (Yale University), who was not involved in the study.

Eubanks’ estimate, posted on the arXiv astronomy preprint server, suggest that the the Vera C. Rubin Observatory should spot more such small interstellar objects, early enough that astronomers can study them in more detail.

‘Oumuamua and Borisov

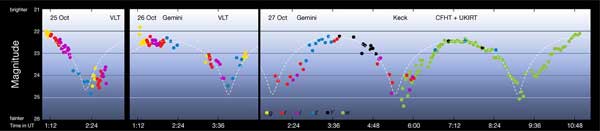

The Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawai‘i spotted ‘Oumuamua on October 19, 2017. By then, the object had already passed perihelion and Earth on its way back to interstellar space. Further observations showed it had the most hyperbolic orbit ever seen, and soon astronomers used telescopes around the world to study it.

ESO / K. Meech et al.

‘Oumuamua was strange indeed: an unusually light, long, and thin object, between 100 and 1,000 meters long but only a sixth to a third as wide. The object showed no cometary fuzz or tail despite having come close to the Sun, yet something besides gravity shaped its orbit.

Scientists have proposed several theories to explain its oddities. The most recent, just out from Steve Desch and A. P. Jackson (both at Arizona State University), is that it's a 45 × 45 × 8-meter divot of nitrogen ice blasted off an exo-Pluto by an impact that ejected it from a young star system half a billion years ago. Laughlin says all the proposed scenarios have problems.

The second interstellar object, 2I/Borisov, was not mysterious at all. Discovered by Crimean amateur Gennadiy Borisov on August 30, 2019, when it was three times Earth's distance from the Sun, it acted like a stray comet that had been ejected by another star system. The dust and water vapor it emitted made it bright and easy to discover months before perihelion. About a kilometer across, its orbit was more hyperbolic than ‘Oumuamua’s.

NASA / ESA / D. Jewitt (UCLA)

An amateur could easily have discovered an object like Borisov in 1980 and its hyperbolic orbit would have been easily identified, so Eubanks concludes such objects must be rare visitors to the solar system. In contrast, ‘Oumuamua was smaller and could only be detected when it came close to Earth, so such visitors might be more common.

Future Prospects

To estimate the prospects, Eubanks turned to data on the motion of local stars recently released by the European Space Agency's Gaia star-mapping mission. He assumed that small interstellar objects in the local region would move in the same way as stars do. Stellar velocities indicate their origins: 92% come from the thin disk near the Sun, where stars are younger than 8 billion years, 7.7% from the older thick and halo of the Milky Way, and 0.4% from beyond our galaxy. (The velocities of ‘Oumuamua and Borisov mark them as coming from the thin disk.)

With only one detection of an ‘Oumuamua-like object, Eubanks assumed the average time needed to find a similar object would be the time it took to find ‘Oumuamua after the start of surveys sensitive enough to find it. Based on that measure, he concludes that on average seven 100-meter-wide interstellar objects come inside Earth's orbit every year.

Eubanks admits that estimate is uncertain, admitting he would be happy if it were within a factor of two. Nevertheless, it's high enough that the Rubin Observatory and other big new telescopes have a good chance of finding more similar interstellar objects. He says objects like Borisov might only show up within Jupiter’s orbit once a decade.

Like the first observations of gravitational waves, the first observations of interstellar visitors show that deploying more sensitive instruments can cross the threshold to exciting and sometimes unexpected astronomical discoveries.

The Rubin Observatory will survey the whole sky visible from its site in Chile over and over again, and its extraordinary sensitivity will discover many more unexpected objects as they pass through the solar system. Other telescopes could then study the new objects in more detail. The European Space Agency's Comet Interceptor mission, planned for a 2028 launch, might be able to fly by a new interstellar visitor. We don't know what else might come our way, but we can expect new and interesting things.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.