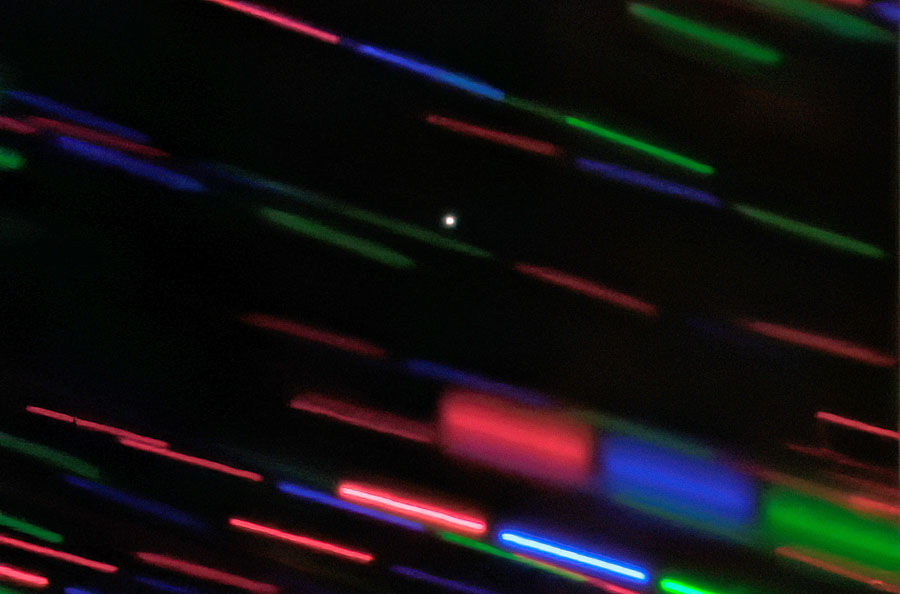

The International Gemini Observatory / NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory / AURA / G. Fedorets

Reports of the loss of Earth's minimoon may have been somewhat exaggerated.

On February 15th, astronomers spotted a faint object roughly the size of a small car, only a few meters across. Designated 2020 CD3, the chunk of rock turned out to be orbiting Earth — but only briefly.

Predictions had the moonlet leaving Earth’s vicinity in April. But only a few short weeks later, reports in The Atlantic suggested the small satellite had already left by March 7th. According to dynamicist and software developer Bill Gray, that’s when the gravitational pull of the Sun became stronger than Earth's.

Now, new research in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society suggests that the small moon will remain a captured object until early May. The difference comes down to how an object's orbit is defined — and the results turn out to be less incompatible than they initially appear.

Has 2020 CD3 Left Earth?

The chaotic nature of 2020 CD3’s movement makes nailing down its exact path difficult. Before it became our minimoon, the object went around the Sun in an orbit similar to Earth’s but more susceptible to interference. Radiation pressure from the Sun likely provided a tumultuous, irregular push, close encounters with Earth and the Moon would also have significant effects.

To determine where the minimoon had come from, as well as when it would be leaving, Carlos and Raul de la Fuente Marcos (both at Complutense University of Madrid) ran 10,000 simulations to show the potential paths the object could have taken. Their simulations had to reproduce its current observed trajectory, determined from 58 recent observations made over a period of 15 days. Based on which paths the simulated object took the most often, the researchers determined its most likely trajectory — in the past and the future.

With the possible trajectories in hand, the researchers had to decide when the moonlet had actually left Earth orbit. They chose to focus on determining whether the minimoon had enough energy to escape Earth if all other objects, including the Sun, were removed. Under those terms, de la Fuente Marcos say that the moonlet won't escape Earth’s gravity until early May.

Gray, on the other hand, based his calculations on the Hill sphere, the region in which our planet’s gravitational influence dominates over the Sun’s. For Earth, that distance is about 1.5 million kilometers (0.01 astronomical unit) — and 2020 CD3 passed outside this distance on March 7th. So according to Gray, the minimoon has already left.

Javier Roa Vicens

“The object spends a good bit of time on the way out in a ‘mixed’ state,” Gray explains. “You can't just treat it as orbiting Earth or just orbiting the Sun; you have to include the gravity of both to get any reasonable result.” Gray therefore remains wary of focusing on the moonlet's energy, rather than its orbit, to determine its status.

Carlos de la Fuente Marcos counters that the method is widely used and is necessary to draw conclusions about the class of objects orbiting or passing by the Earth.

Uncertainties and a “Moon-moon”

Because the researchers rely on a statistical look at the moonlet's path, its past is related to its future. And 2020 CD3 is unique for the Moon's past influence on its orbit.

"This is probably the first known near-Earth object for which the influence of the Moon is truly important," Carlos says. Lunar encounters were significant enough that at some points, 2020 CD3 could have become a satellite of the Moon rather than Earth. That would have made it a “Moon-moon,” a hypothetical class of objects proposed in 2018. In roughly 10% of the simulations, 2020 CD3 became a Moon-moon for anywhere from a few hours to a few days.

According to de la Fuente Marcos, each close encounter with Earth or the Moon makes reconstructing the orbital evolution into the past "rather challenging."

Gray agrees. "It really is a chaotic system," he said. "Any small uncertainty we have now gets to be a bigger one as you go back [in time]."

That knowledge could improve if images from the past year or two reveal the moonlet. "That would cause its orbit to snap into place even more than it already has," Gray said. Such observations could narrow the uncertainties around when the object first entered orbit.

After its discovery, the moonlet was observed again in late February and twice more since the publication of de la Fuente Marcos's research. "We have a really solid, excellent idea as to where the object has been during that time, and a bit before then, and a very long time after that," says Gray. That is, astronomers know it will leave Earth orbit eventually — but what the near future holds is still uncertain.

Minimoons Aplenty

Whether the tiny moon has really made its exit or not, it'll be back: According to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Small-Body Database, 2020 CD3 could make its next closest approach on March 20, 2044.

In the meantime, we might have other company.

"The fact that 2020 CD3 was only discovered when it was leaving the neighborhood of the Earth-Moon system strongly suggests that other similar objects may have been missed," de la Fuente Marcos says.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.