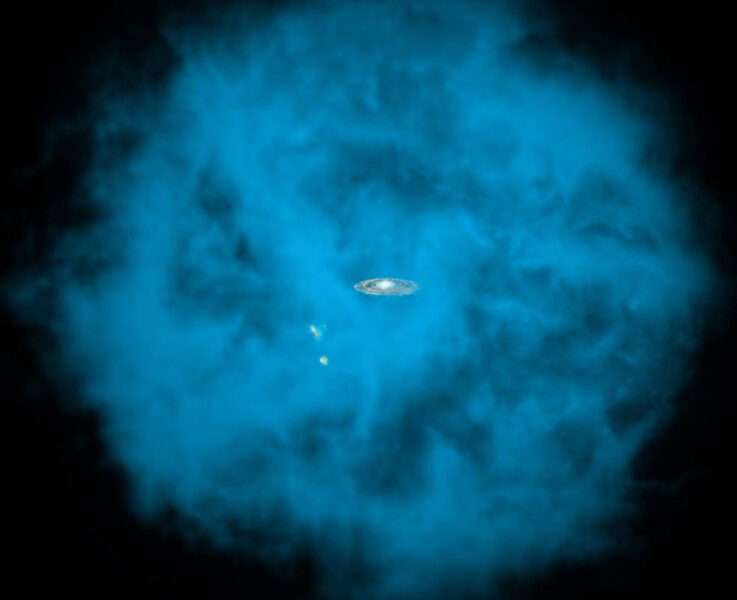

Galaxies swim in hot gas that extends much farther out than their stars — and plays an important role in the galaxy’s evolution.

NASA / CXC / M.Weiss / Ohio State / A. Gupta et al.

Galaxies are pretty big. The Milky Way's stellar disk, for example, spans some 100,000 light-years. But new observations show that galaxies' extent is actually much greater than that — more like millions of light-years across.

Sanksriti Das (Ohio State University) presented X-ray observations of the Milky Way-size spiral galaxy NGC 3221 at this week’s virtual meeting of the American Astronomical Society. She and her colleagues took spectra of X-rays emitted by hot gas all around this galaxy, using the XMM-Newton and Suzaku space telescopes to provide direct evidence of the existence of a halo that extends well beyond the galaxy's stars.

To See a Halo

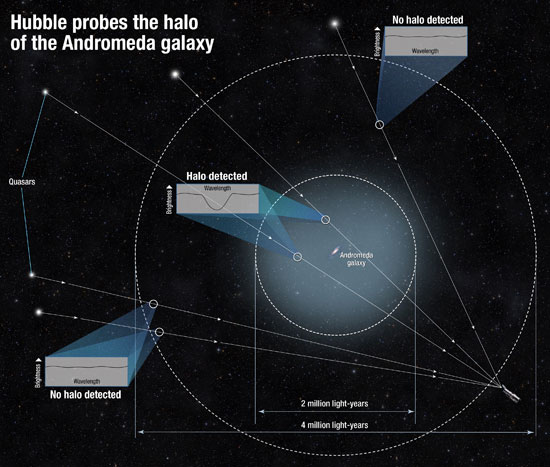

Astronomers have long been detecting halo gas indirectly, by the way it absorbs the light of quasars or disperses brief flashes of radio waves. That’s because the gas is exceedingly difficult to detect on its own. It’s so thinly spread out that there are only 100 atoms of it per cubic meter. For comparison, the tenuous gases that remain after a supernova explosion are on the order of millions, even hundreds of millions of atoms in the same volume.

NASA

Yet, because these hot, hard-to-find atoms are spread across such a huge volume, they amount to the same number as found in all the stars of the galaxy. That’s a huge amount of “normal” matter that astronomers wouldn’t otherwise see. (That’s not to confuse this hard-to-see matter with dark matter — dark matter is a different beast entirely and would remain invisible to X-ray telescopes.)

Astronomers have directly seen the extended halos around only a few galaxies, such as the massive spiral NGC 1961, whose halo extends to almost 200,000 light-years.

NGC 3221, like NGC 1961, is a spiral galaxy, but it’s more akin to the Milky Way in mass. Yet Das’s team detects very hot, X-ray-emitting gas all the way out to 500,000 light-years around this galaxy. The 2 million-degree gas outweighs the disk of stars, to the tune of 10 billion Suns.

How Hot Is Too Hot?

While theorists have often assumed that the gas in such halos is uniformly hot, the X-ray observations taken by Das’s team show this isn’t the case. The gas nearer the galaxy is hotter — what’s more, it’s about twice as hot as expected. However, that’s exactly what has led some other astronomers, not involved in the study, to question the results.

“I rate this as a bona fide detection,” says Philip Kaaret (University of Iowa). “The question is the interpretation.”

Joel Bregman (University of Michigan) goes a step further, doubting the detection itself. “The observation that Das presented is very challenging,” he notes. “The issue is that one needs to remove a background from the image.”

Because NGC 3221 has roughly the Milky Way’s mass, Bregman explains, its halo would have roughly the same temperature as the Milky Way’s halo. So Das and her colleagues are viewing NGC 3221 through the screen of our galaxy’s own hot gas, which makes it difficult to separate out what emission belongs to the distant spiral and what belongs to the Milky Way.

“I'm not ready to engrave this one in stone, but I look forward to future observations,” Bregman says. Das, too, hopes for additional observations to confirm the halo — and better understand its behavior.

Whether this detection pans out, the researchers agree on one thing: A galaxy's halo is more than a curiosity, it's a crucial part of the galactic ecosystem. Halo gas rains down on the galaxy, spurring the birth of new stars. Then the winds of those stars, as well as their eventual explosions as supernovae, fountain gas back out into the halo.

The constant give and take, Das says, means that halos "should be viewed as something in the galaxy rather than around the galaxy.”

7

7

Comments

Cousin Ricky

June 3, 2020 at 4:41 pm

> “Yet, because these hot, hard-to-find atoms are spread across such a huge volume, they amount to the same number as found in all the stars of the galaxy.”

There has to be some error here. Using a high estimate of the number of stars in the Milky Way, that number of atoms would only fill a cube 4 km on a side.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Stephen Gagnon

June 3, 2020 at 8:01 pm

When I (roughly) work it out, using a radius of 200,000 ly and a particle density of 100 atoms per cubic meter, I get a total mass of about 1*10^42 grams. If the sun has a mass of about 2*10^33 grams, then that's enough to make about 500,000,000 suns, or about the number of stars in the Milky Way. So, the numbers don't seem too far off to me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

camlinhall

June 6, 2020 at 5:44 am

Or maybe 500 billion?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Cousin Ricky

June 4, 2020 at 1:27 pm

It seems that I parsed the sentence incorrectly. Stephen’s interpretation seems more in line with what the article meant.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ccormsby

June 5, 2020 at 7:06 pm

But it is not in the right place ... the vast majority of it is outside the galaxy so would not affect the periods/orbits of the stars around the galaxy center.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mark Holm

June 4, 2020 at 7:32 am

How does this hot gas halo affect the calculation of dark matter mass? The halo doubles the mass of the galaxy and is in the right place to have the same gravitational effect as dark matter.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nick

June 5, 2020 at 5:58 pm

I need a double-check on the 100 atoms/meter^3 figure and that this is not for the intergalactic medium. The interstellar medium inside our galaxy (inside the 100,000 ly part with the stars+gas+dust) is about 1 atom/centimeter^3. This story is about the hot haloes surrounding a galaxy that is about 100 atoms/meter^3 while the super-thin gas between the galaxies (intergalactic medium) is about 0.1 atom/meter^3. Correct? I'm trying to distinguish this story from another one published in Nature https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2300-2 which is about the gas between the galaxies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.